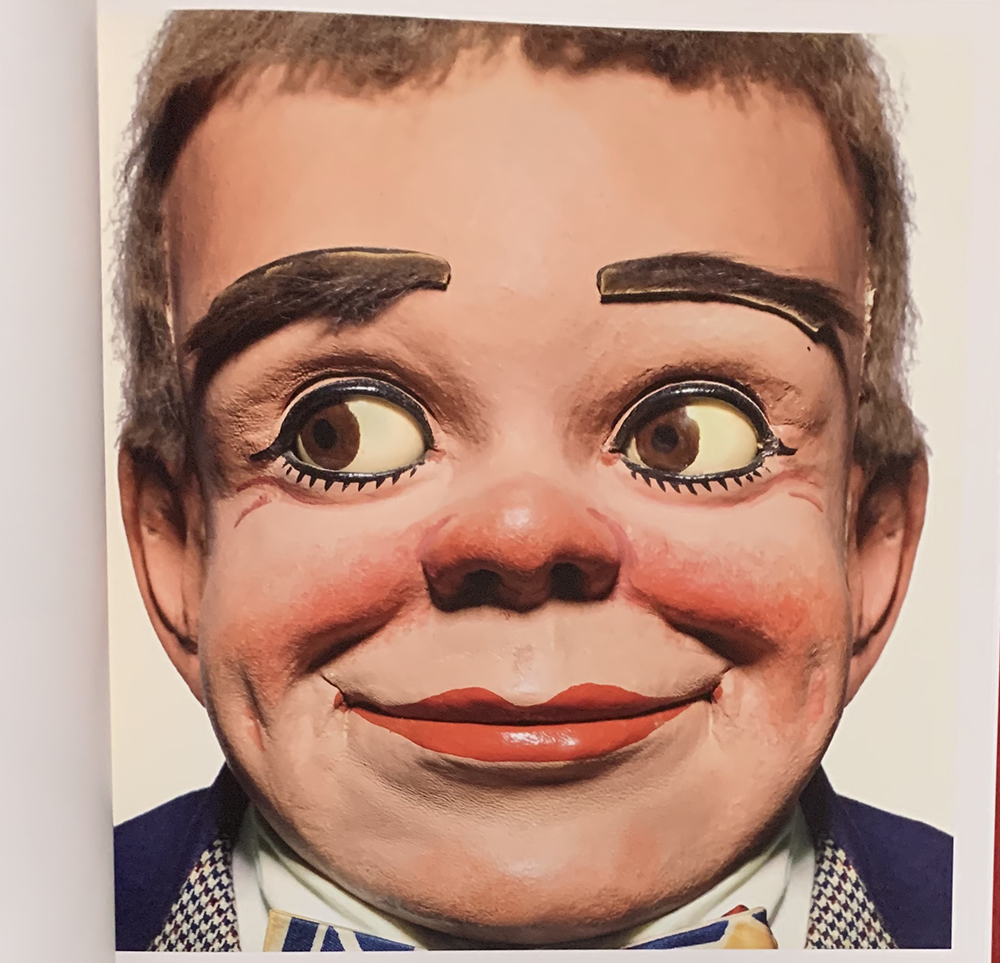

A page from Matthew Rolston’s “Talking Heads” featuring a ventriloquism dummy called Reese Boy.

Ventriloquism has always fascinated me. The talent to throw one’s voice has led to great entertainers, such as Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy, who started in vaudeville and moved into radio (yes, ventriloquism on radio!). Of course, for others it’s the stuff of nightmares. The Twilight Zone’s 1962 episode, The Dummy, in which a dummy seems to come to life, may be partly responsible. That, and the generally haunting look the dolls tend to have.

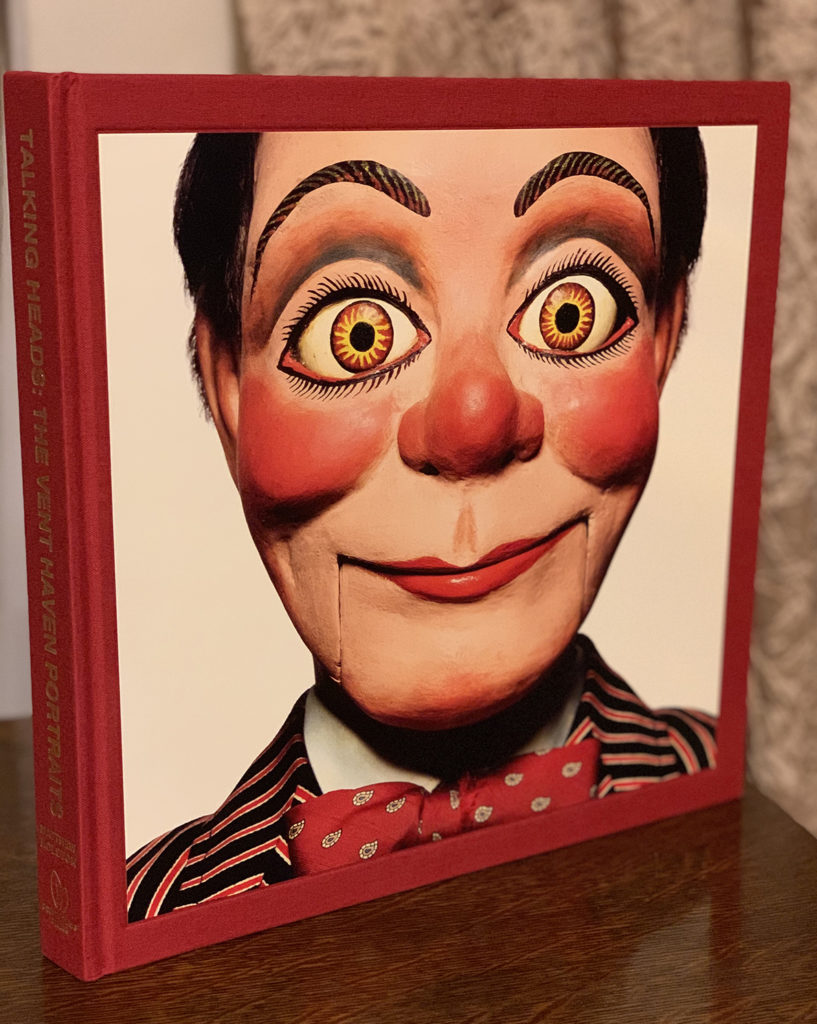

Those haunting faces are the reason I purchased Talking Heads: The Vent Haven Portraits, by Matthew Rolston. The book features a hundred beautifully creepy photos of the Vent Haven Museum’s collection—the world’s only museum dedicated to ventriloquism. Located in Fort Mitchell, Kentucky, the museum’s gathering of lifeless dummies have been smiling and gazing at visitors since 1973.

Matthew Rolston’s “Talking Heads” features a hundred portraits of ventriloquism dummies.

The book sent me on a ventriloquism path of research that led to a time when throwing one’s voice entertained others, or oneself, without the use of any dummies. The skill, after all, is perfect for practical jokes.

Take for instance Cardinal Richelieu. Early in his reign as Louis XIII’s chief minister, Richelieu had a little fun by urging a ventriloquist to throw his voice at the Bishop of Lavaur, Charles François d’Abra de Raconis, during a walk to the Tuileries.

“Abra de Raconis! Abra de Raconis!” the bishop heard from an unknown source. “Abra de Raconis, I am the spirit of thy father. For many years I have endured the pains of purgatory in expiation of my transgressions. God in His divine mercy has permitted me to come to warn thee against the reprehensible course of life thou art leading, courting the favours and patronage of the great, and neglecting thy religious duties.”

The bishop was in shock and instantly went pale as Richelieu and his attendants watched in glee. They told the poor bishop that they had heard nothing. An 1895 recounting of the tale claimed Raconis was “half dead with fright” for days before he could be convinced that it was nothing more than a trick.

At the end of the 18th century a ventriloquist named Burns used his talents to set a fish seller straight.

“Is this fresh?” he asked the woman.

“Fresh, my dear,” she answered, “only caught this morning.”

“Don’t you believe her,” the fish appeared to say. “I have been out of the water for more than a week, and you know that well enough, you old deceiver.”

The fish seller couldn’t believe what she’d just heard and from then on became a more honest peddler.

Another vent story of the animal-purchasing variety involved famed Frenchman Louis Comte and a peasant woman with a fat pig.

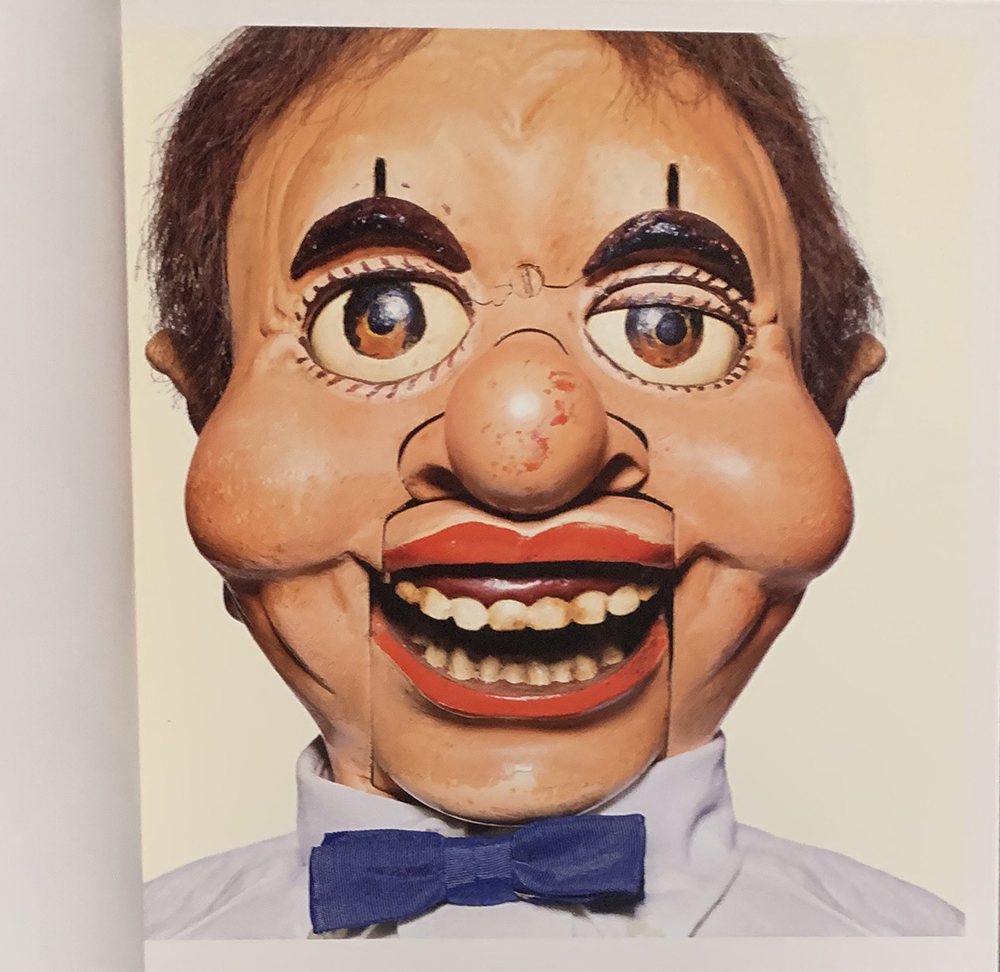

Another page from Matthew Rolston’s “Talking Heads” featuring a ventriloquism dummy called Uncle Eddie.

“What’s the price of this animal, my good woman?”

“One hundred francs, Sir?”

“One hundred francs! it is too much! I will give you ten crowns.”

“Nonsense, don’t talk to me; if you won’t give a hundred francs, be off with you.”

“Stay, I will ask the piggy himself. How much are you worth, my fine piggy? One hundred francs?”

To the peasant’s surprise, the piggy answered, “I am not worth a hundred pence; I am measly, and my mistress is trying to take you in.”

Sometimes the jokes went a little too far, like in the case of Thomas Britton, a 17th-century musician and small-coal merchant. One of his fans, who happened to be a practical joker, invited a ventriloquist to throw his voice at Britton and warn him that he had only a few days to live. To avoid such a fate, he’d have to drop to his knees and say the Lord’s Prayer. So he went home and did just that. Britton never rose from his knees again.

Dummy or no dummy, ventriloquism, it seems, has a history of scaring people to death.