Spirit photography blossomed in the latter half of the 19th century, leading many to believe that ghosts of loved ones were right beside them. Creative photographers were opportunists, capitalizing on a new medium and new beliefs. But French physician and parapsychologist, Dr. Hippolyte Baraduc took the concept one step further. He claimed to take photos of thoughts and emotions—and even the soul.

Baraduc claimed this 1896 image shows a “vital force” around a child.

In 1896, he informed the Paris Académie de Médecine that he had successfully photographed thoughts. According to reports, his method was simple: “The person whose thought is to be photographed enters a dark room, places his hand on a photographic plate, and thinks intently of the object the image of which he wishes to see produced.”

Most of the images Baraduc supplied as evidence were very cloudy, but some, according to reports, offered distinct “features of persons and the outlines of things.”

Baraduc even claimed it was possible to produce thought photos from a distance, simply by willing an image from the mind to the photographic plates.

The doctor, along with others, believed we all exhibited auras. Our emotions produced energies. These too, Baraduc claimed, could be captured on film.

Two years after his announcement to the Académie, the doctor addressed the Society of Psychical Sciences in Paris. Newspapers reported that he informed the group that photography could “measure and register the volatile matter of which every living thing is constantly ridding itself.”

Baraduc explained that he experimented on himself for ninety days by photographing himself whenever he felt his soul was particularly active. This early pioneer in selfies said the luminous points of images were full of light and vitality when he was happy, and dim when nervous or sad. He found similar results with other people.

But he didn’t just perform tests on humans. “I have experimented on pigeons, as well as on fresh milk,” Baraduc said. “Moreover, there is evidence that even plants possess a sufficient amount of sensibility to render them fit subjects for such experiments. A Portuguese whom I know photographed some plants which he had just gathered, but obtained no result. Thereupon he tore them to pieces, crushed them in his hands and otherwise tortured them, and this time he was not disappointed. The plate contained fluidic impressions very similar to those which are obtained when a sickly person is the subject.”

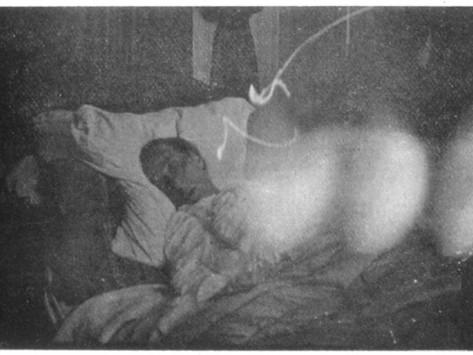

Hippolyte Baraduc took this photo of his wife 20 minutes after her death. The misty cloud, he claimed, was her soul.

In April of 1907, Baraduc took his studies to another level. His son, André, passed away at the age of 19. Nine hours afterward, Baraduc photographed the coffin and discovered a misty cloud emanating from all around it. Six months later, on October 15, Baraduc sadly had a chance to continue his studies with his wife, Nadine—at her death bed. With his cameras all set up for the event, he captured a photo twenty minutes after her passing which he claimed revealed her departing soul. The image appears to show three misty luminous clouds over her body. A photograph taken about thirty minutes later exhibits one larger cloud. Soon after it left the body and floated into Baraduc’s bedroom, creating an icy breeze before leaving entirely.

Baraduc took another photo of his wife nearly an hour after her death. Here, the three misty clouds seem to form one larger cloud.

Hereward Carrington covered the phenomena in his 1921 book, The Problems of Psychical Research:

There is no inherent absurdity in the idea, as many might suppose. Of course the spiritual body would have to be material enough to reflect light waves, but where is the evidence that it is not? There seems to be much evidence, on the contrary, that it is. It must be remembered that the camera will disclose innumerable things quite invisible to the naked eye, or even to the eye aided by the strongest glasses or telescopes. Normally, we can see but a few hundred stars in the sky; with the aid of telescopes, we can see many thousand; but the photographic camera discloses more than twenty million! Here, then, is direct evidence that the camera can observe things which we cannot see; and, indeed, this whole process of sight or ‘seeing’ is a far more complicated one than most persons imagine. As Sir Oliver Lodge has pointed out, there is no reason why we should not be enabled to photograph a spirit, when we can photograph an image in a mirror—which is composed simply of vibrations, and reflected vibrations at that! We are a long way from the tangible thing, in such a case; and yet we are enabled to photograph it with an ordinary camera. Any disturbance in the ether we should be enabled to photograph likewise—if only we had delicate enough instruments, and if the ‘conditions’ for the experiment were favourable. The phenomena of spirit-photography, and especially the experiments of Dr. Baraduc, to which I shall presently refer, would seem to indicate this.”

Others think all these effects could’ve come from tiny pinholes behind the camera lens. Though Carrington’s theory is much more exciting.

![Lady Wonder - By Francis Wickware (Dr. Rhine and ESP. Life Magazine. April. 15, 1940) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.weirdhistorian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Lady_Wonder_Horse-By-Francis-Wickware-Dr.-Rhine-and-ESP.-Life-Magazine.-April.-15-1940-Public-domain-via-Wikimedia-Commons-235x190.png)