Earthlings often imagine Martians as belligerent, as in the War of the Worlds radio broadcast of 1938 or the 1996 classic Mars Attacks!. But for Dr. Hugh Mansfield Robinson, a London lawyer and former town clerk of Shoreditch in the early 20th century, the Martians were a gentle people who only wanted peace.

Sure, the inhabitants of the Red Planet might look a little alarming—they were more than seven feet tall with huge ears and large shocks of hair, Robinson reported. But other than that they were much like humans, living in houses and driving cars, and enjoying simple pleasures such as drinking tea and smoking pipes. But when it came to eating, they were far more advanced. Martians electrified their fruit trees, which gave its produce all the nutrients these lifeforms needed.

Robinson knew all this because he had been telepathically communicating with a Martian woman named Oomaruru, or so he claimed. The large-eared lady wore a flowing green dress and was described as having dark penetrating eyes, a curious nose and a half-smiling mouth. A pain in his left temple let him know when she, or other Martians, were trying to communicate.

Robinson also learned of a lower form of Martian beings with heads shaped like walruses.

Though this may sound absurd today, at the turn of the century many scientists believed in the possibility of life on Mars. The discovery of what astronomers identified as canals on the Red Planet (first observed by Giovanni Schiaparelli in 1877) had excited imaginations, and with inventions like the telephone and radio, science was continually turning what had once seemed the impossible into the possible. Furthermore, the rise of Spiritualism in the 19th century—based on the idea of communication with the dead—remained popular, with notable advocates like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle encouraging people to believe contacting the beyond was a worthwhile pursuit. Was contacting Mars really so much of a stretch?

He had claimed to be in contact with Oomaruru from as early as February 1926, when he wrote to psychic researcher, Harry Price. In his letter, the doctor claimed to have patented an instrument called a Psychomotormeter that allowed him to communicate with Martians. He heard their voices through a floating trumpet and a medium and wanted Price to record them on a Dictaphone.

Price agreed, and Robinson set up a Martian séance for the afternoon of March 9, with his medium of choice, Mrs. St. John James, and Oomaruru.

“She is very pleased at the idea of being treated with scientific seriousness,” the doctor wrote Price. He added that “a very cultured giant” called Pawleenoos may participate as well.

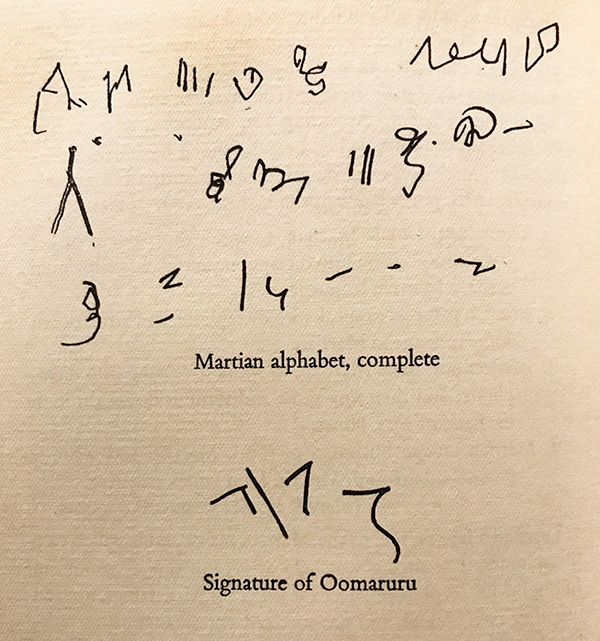

When the day arrived and the session began, Mrs. James fell into her trance and channeled messages from the Martians. Oomaruru was kind enough to control the medium’s hand and write the full Martian alphabet, which looked like a series of scribbles from someone trying to write with their non-dominant hand. Pawleenoos, who joined the festivities, sketched his portrait, and a Martian princess even sang a love song.

“If the song was not Martian, it was certainly ‘unearthly,’ and sounded rather like a solo by a crowing cock,” Price recalled in Confessions of a Ghost Hunter. “There was nothing musical about it.”

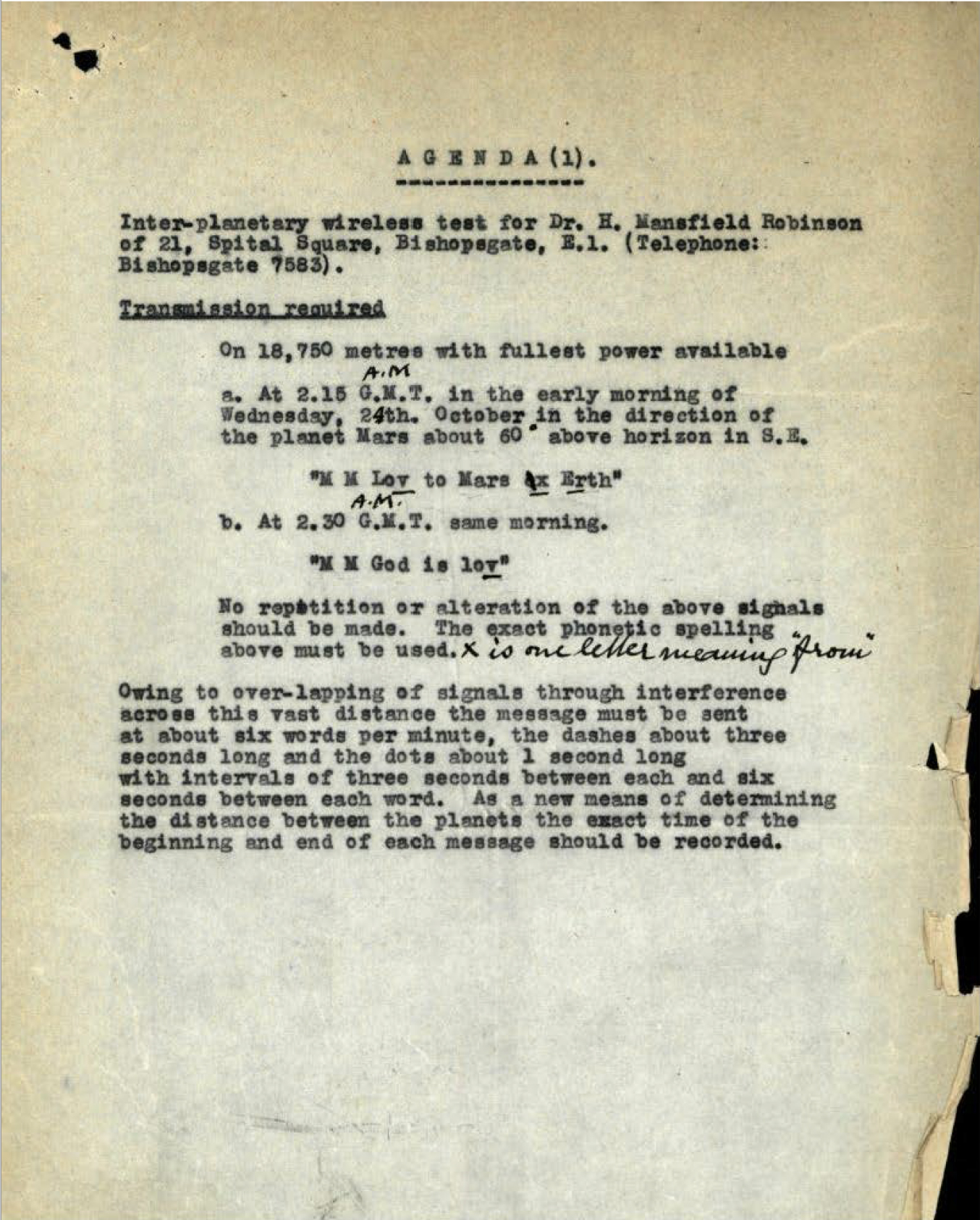

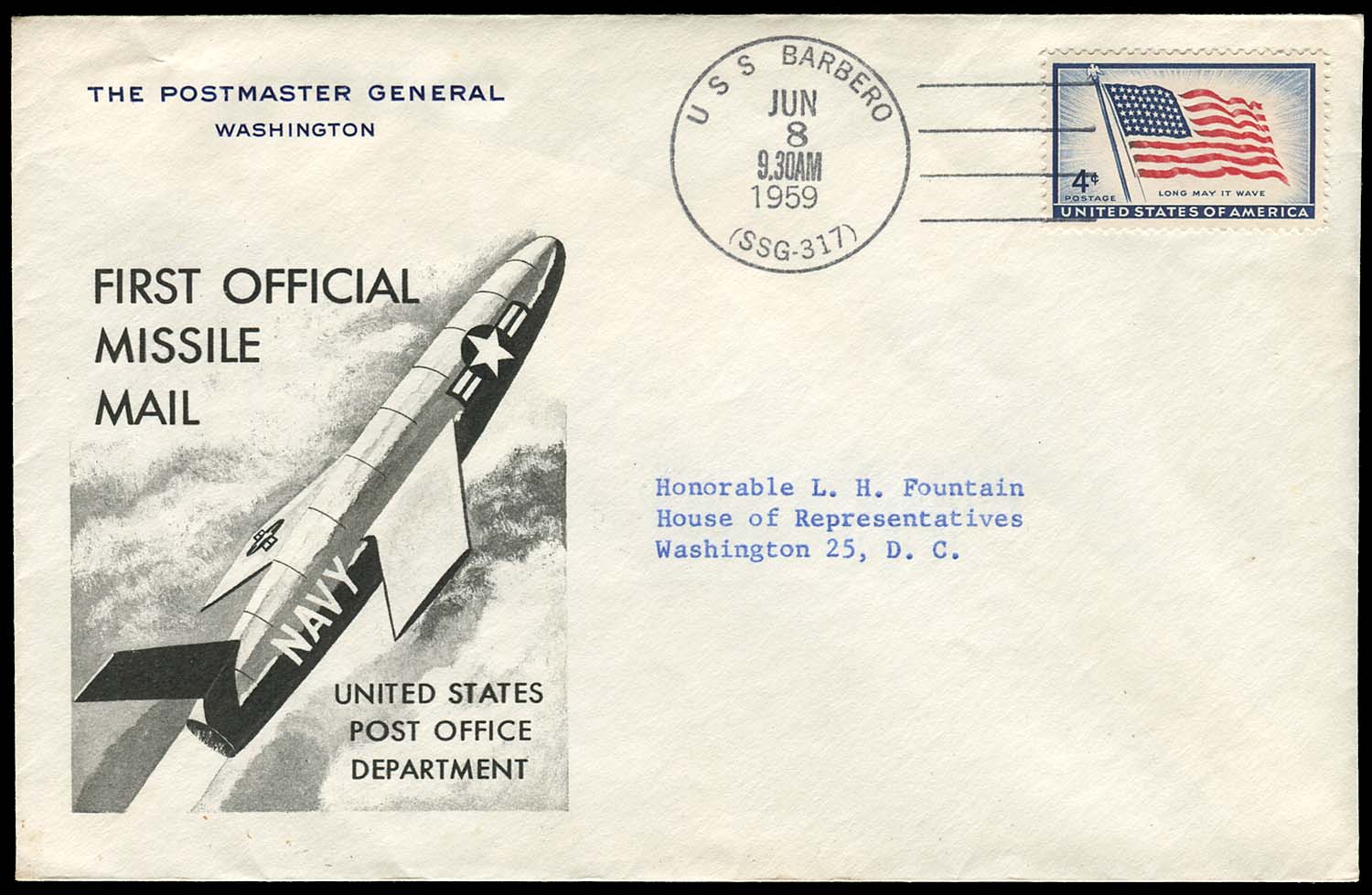

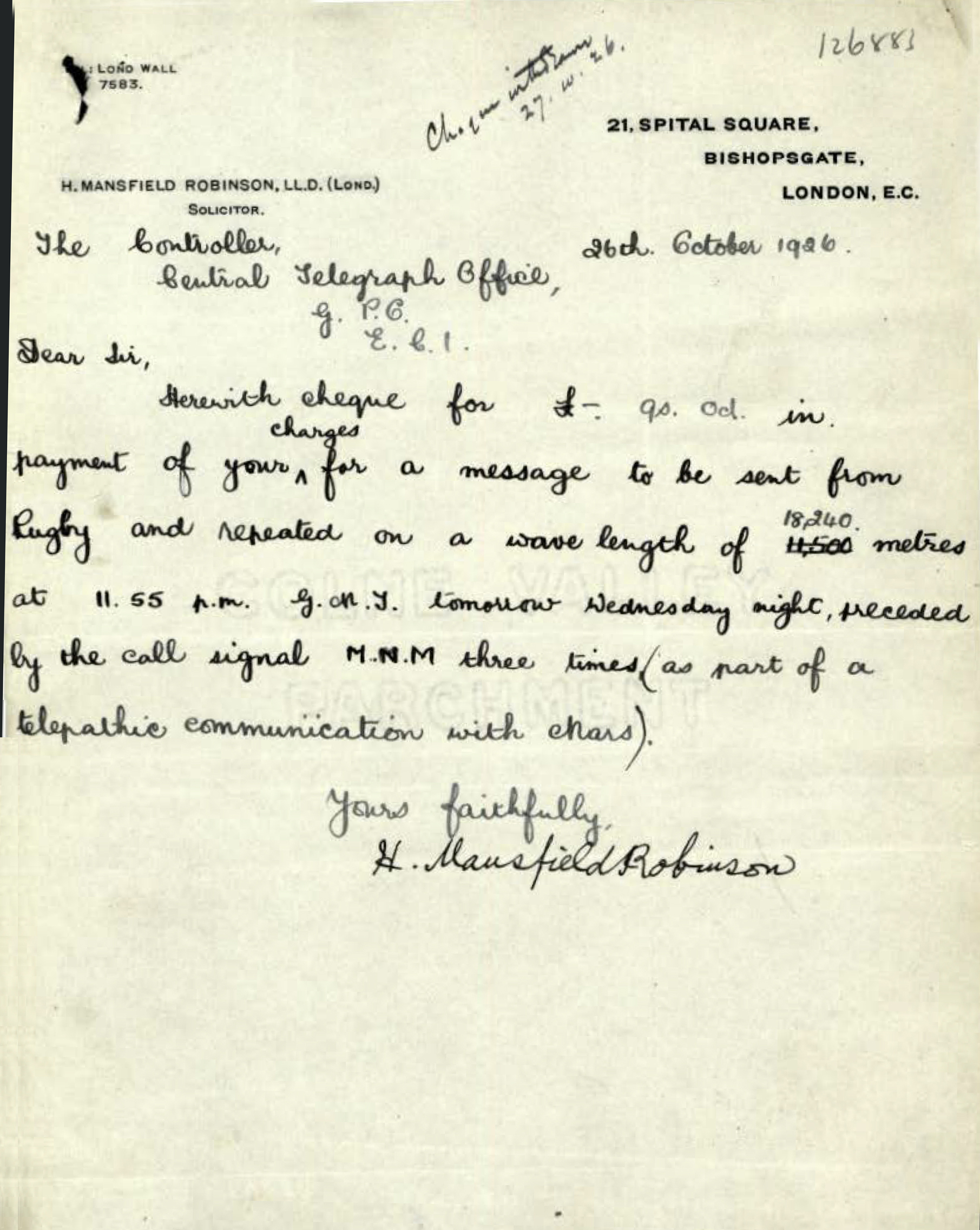

In 1926, Dr. Hugh Mansfield Robinson made arrangements with London’s Central Telegraph Office to transmit a message to Mars. Courtesy of BT Heritage & Archives.

Later that year, despite Robinson’s self-proclaimed telepathic abilities and his apparent success with his medium, he turned to radio waves at the post office for further communication attempts. Mars was then in its closest position to earth—just 35,000,000 miles away—so the doctor thought the signals might be able to reach it.

An October 27th memo unearthed from London’s Central Telegraph Office explains that Robinson made arrangements to transmit a message to Mars for its standard long-distance rate of just 18 pence per word (about 35 cents), and that he wished to know the exact wavelength and time of the transmission. Apparently Oomaruru could share this information with the director of the largest wireless station on Mars.

“Dr. Mansfield Robinson is singularly serious in this business and we may expect other messages from him,” the memo reads. “I do not think we could have any conscience pricks as regards taking the money for he is perfectly sane and seems to have devoted his life to the study of possible intercommunication with the planet.”

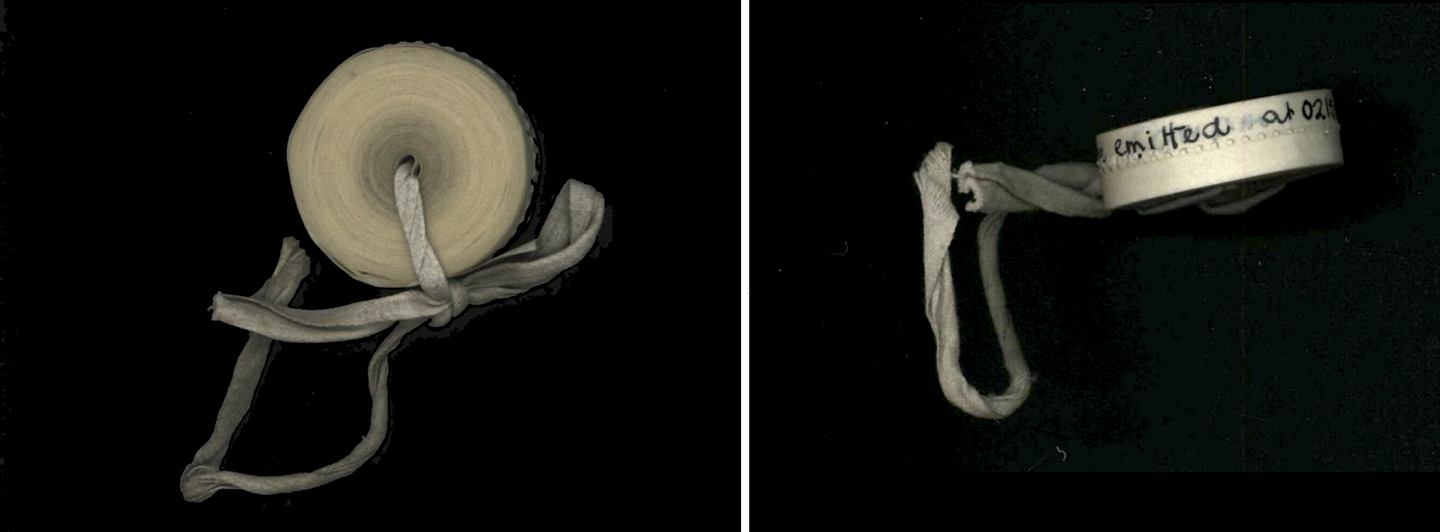

The message was scheduled for 11:55 that evening using the doctor’s requested wavelength of 18,240 meters. It was to be transmitted from Rugby, the largest and most powerful wireless station in the world at the time, and consisted of three words: Opesti, Nipitia, Secomba. (Their meanings remain a mystery.)

Postal clerks stood by with a receiver tuned to a wavelength of 30,000 meters, which Robinson said was the Martian’s preference. Sadly, they received no response.

According to The New York Times, Robinson claimed Oomaruru only received a “repetition of the letter M” and he “coyly refused further information about the fair Martian.”

Sir Oliver Lodge, a British physicist and proponent of Spiritualism, was quoted as saying, “We have not got into touch with Mars, and I doubt if we are likely to do so. If we did get anything there, how are they going to know what we are talking about? They do not understand the Morse code; neither do they understand the English language. So how are they going to understand?”

Robinson didn’t trouble himself with such concerns. He waited two years for the Red Planet to get close to Earth again. And then he made another attempt.

Once more, the post office agreed to dispatch his message. A memo stated that its reasons were “mainly in order to obtain free publicity for Rugby.” After all, press coverage would promote their long-distance rate far more effectively and efficiently than paid advertising, officials reasoned. The memo further noted that “it was made clear that we did not regard ourselves as co-operating in a scientific experiment, but were merely performing the service at his request as a commercial proposition.”

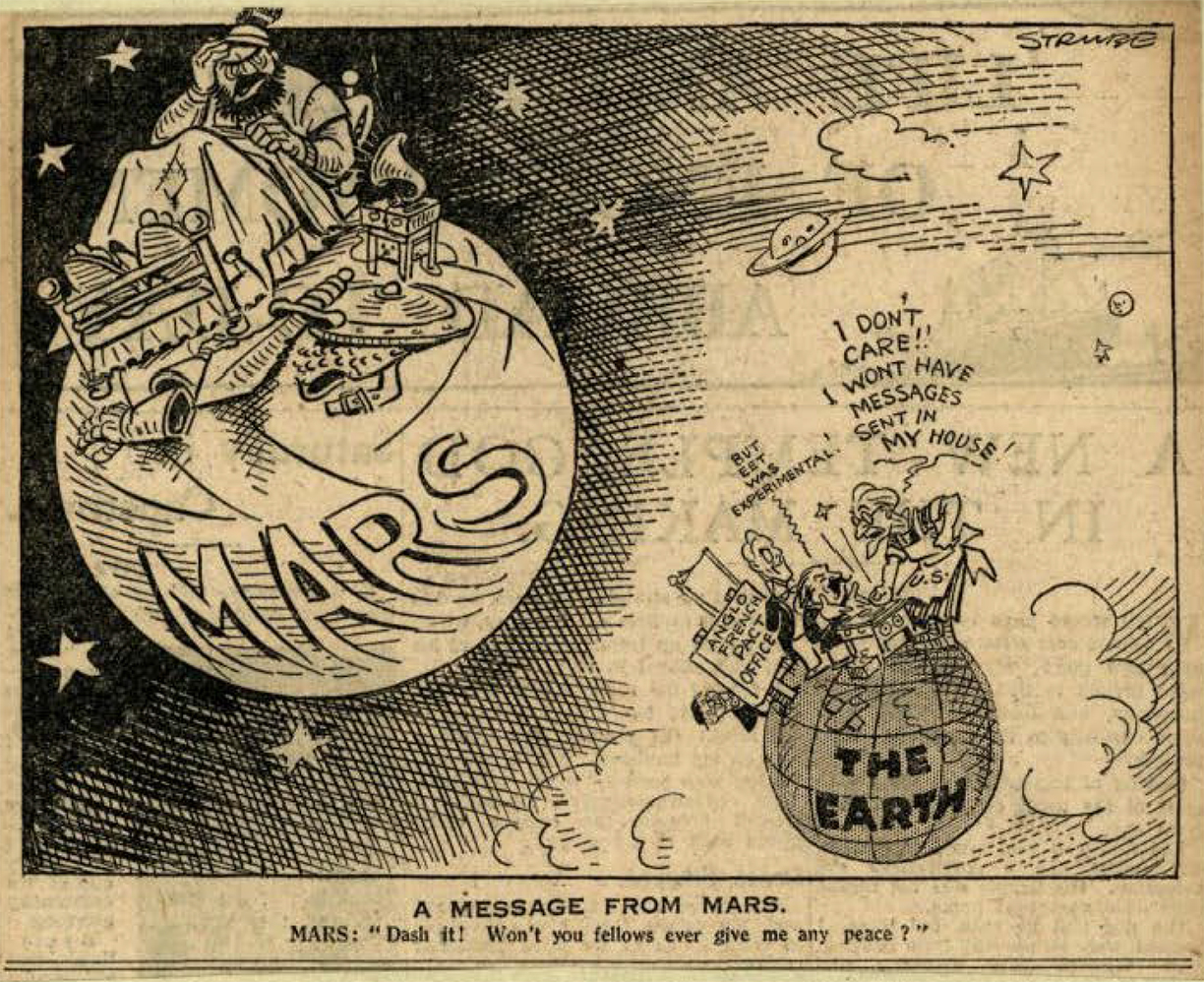

This time, editors from two London newspapers wrote to the post office requesting a presence at the transmission, but the Postmaster General rejected them.

The message, which read, “Mar la oi de earth,“ (Robinson translated as “Love to Mars from earth”) was transmitted at 2:15 am on October 24. Even though the media was denied attendance, the press gave it a great deal of coverage.

One paper even reached out to a professor at the Yale Observatory, who believed radio signals to Mars were futile and that “the inhabitants of Mars may be more hideous than we can imagine—with no heads, perhaps, and maybe no brains.”

The professor was proven correct on the “futile” part. Again, no response came through.

Of course, Oomaruru continued to communicate with Robinson telepathically. “Go home to bed, but do not be downheartened,” she told him after the failed attempt.

Robinson, however, blamed the post office’s inept equipment. “The wave length of 18,700 meters used by the post office does not go through the heavy-side layer of rarefied air, and therefore signals are reflected around the earth,” he told the Associated Press.

“The Martians were very annoyed that the signals could not come to them,” he added. “They were sitting up for hours to receive signals. They laugh at our scientists because they themselves have got rid of atmospheric troubles altogether, and yet we have not.”

Undeterred, Robinson decided to try another transmission in December, but this time from Brazil, using 500-kilowatt signals with wavelengths at more than 21,000 meters. Similar to his previous message, this transmission read, “God is love; from earth to Mars.”

Unfortunately, changing hemispheres did not change the results. A Brazilian newspaper suggested that the Martians probably didn’t understand English, and that Robinson should have tried sending his message in Portuguese or another language, “on account of the greater difficulty of Shakespeare’s tongue.”

Robinson’s mission went quiet until January 1930, when he apparently dispensed with radio communication and reported that he’d telepathically conducted an interview with Oomaruru for the United Press. In his alleged conversation, she suggested opening a College of Telepathy. She also expressed dismay at the lack of world peace after nearly 2000 years of “listening to the teachings of Jesus.”

Telepathy, Oomaruru believed, would make our world a better, more peaceful place. Not only would it help us reach Mars, it would also help simplify communication right here on Earth. Robinson believed it was the “missing link in progress” and felt it had been neglected by scientists “in spite of its obviously tremendous value.”

He was also frustrated by the inefficiencies of the telephone, which telepathy would solve. “One in three calls do not materialize,” he said. “You either get a wrong number, a busy signal, or a ‘they don’t answer’ from the operator. All this will be done away with when the world learns to telepathize.”

A benefactor planned to help fund the college with the sale of artwork, which the doctor valued at nearly a quarter million dollars.

Six months later, an article in The Sunday Morning Star reported that Robinson had opened the College of Telepathy, staffed with six teachers and a telepathic dog named Nell. To help build the student body, he offered free tuition to the first seven pupils. He explained that each would be required to have “complete chastity and abstinence from flesh, alcohol and tobacco, coupled with good health and a desire to seek spiritual development.” Nell’s role was not clarified.

The article also noted that at the time of its writing there was only one student, named Claire. In addition to meeting the aforementioned requirements, she also signed a membership declaration in which she agreed to obey its rules, keep its secrets (unless “compelled by a competent court of justice”), and use her powers for the benefit of others.

Robinson hoped for more female students because he didn’t believe men would be able to beautify their souls and bodies “even for the sake of telepathy.”

To find other pupils like Claire, he appealed to their vanity. “What more could one offer to women than the assurance that their beauty would be enhanced by special treatment which would be provided for by an annex of the College of Telepathy, viz, a beauty college?” the article said, describing Robinson’s plan. “Under the expert guidance of a graduate telepathist, ugly women—if any can be found who will admit it—may flock and be made beautiful, then telepathic.”

This annex was to be surrounded by the beauty of nature on the South Coasts of England.

No further details on attendance or successes were ever reported in the press. However, Robinson made headlines again in 1933 after claiming to be telepathically in touch with Cleopatra, who was living on Mars as a farmer’s wife. This may not have pleased his own wife, who once told reporters that she wouldn’t allow his experiments to be conducted at home. “There will be no more of that foolishness in this house,” she said.

Robinson died in 1940 at age 75, without ever having made radio contact with Mars. For the last few years of his life, at least, it seems he respected her wishes.

A shorter version of this story originally ran on Mental Floss. See more on Dr. Hugh Mansfield Robinson here, and an earlier attempt at contacting Martians here.

Want to read more about Oomaruru and other Martians? Buy my new book, The Big Book of Mars on bookshop.org, Amazon, at Barnes & Noble, or wherever you buy books.