Charles Byrne was a 7’-7” giant who became a sensation in late 18th-century London. John Hunter was a renowned anatomist and surgeon who wanted his bones.

Byrne, known as the Irish Giant, was born in Derry, Ireland, in 1761. A condition called acromegaly caused his extreme growth, which was at times reported as reaching 8’-2” (the heights of giants were commonly exaggerated). As a teenager, Byrne left home to capitalize on his unusual height, making his way through Scotland and eventually to London by the age of 21.

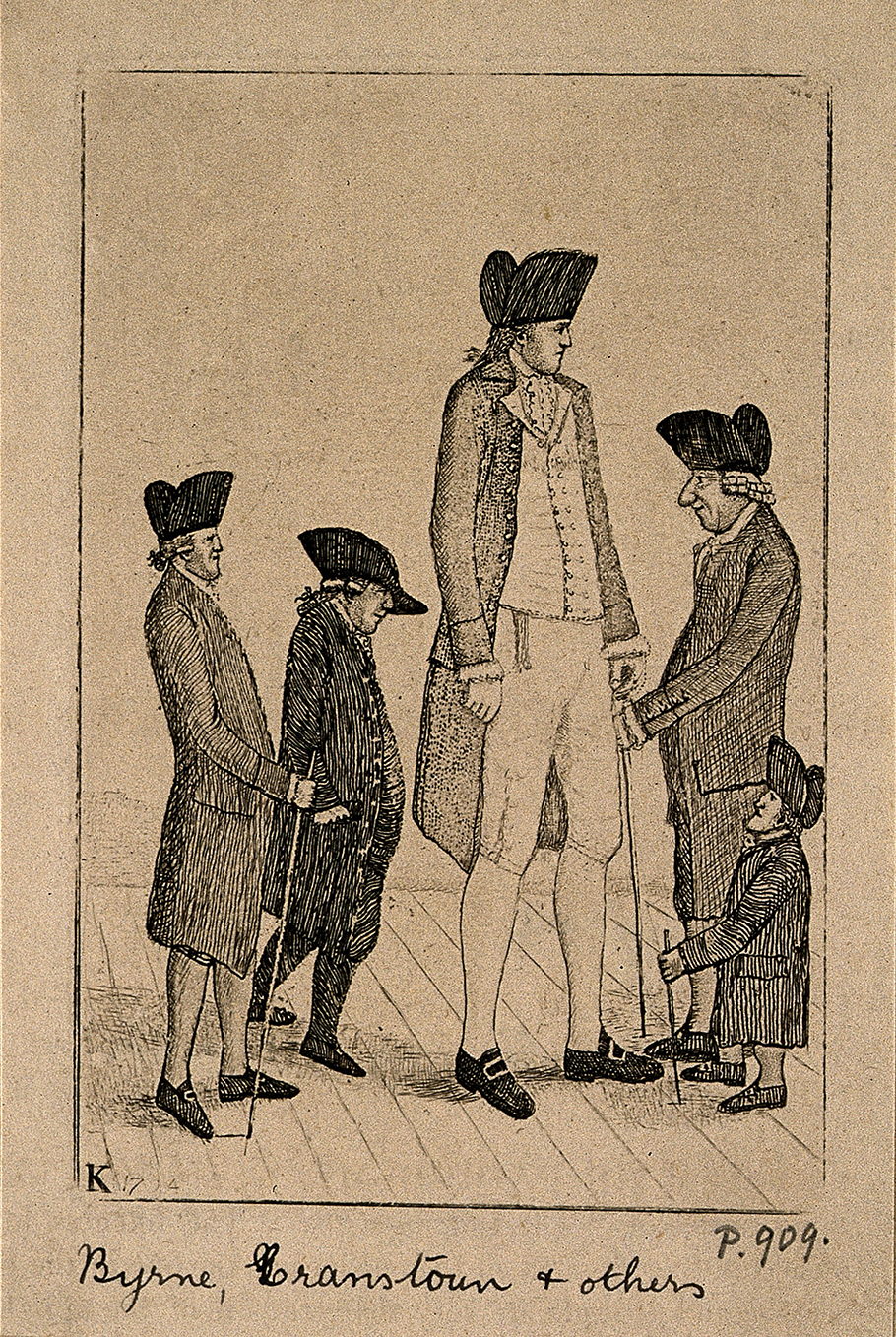

Charles Byrne, the Irish Giant, George Cranstoun, a dwarf, and three other normal sized men. Etching by J. Kay, 1794. This file comes from Wellcome Images, a website operated by Wellcome Trust, a global charitable foundation based in the United Kingdom.

An article in the June 20, 1782, edition of The Morning Herald announced Byrne as “The astonishing Irish Giant, whose height surpasses the Patagonian; with admirable symmetry of body, and esteemed to be the best proportioned ever seen.”

Patagonians were believed to be a race of giant Europeans who stood twelve to fifteen feet tall. They were first mentioned in the early 1500s. Byrne was no Patagonian, but he was also no myth. People flocked to see him in the flesh, namely at Cox’s Museum in Charing Cross.

Byrne was of particular interest to John Hunter. The doctor was a member of the Company of Surgeons and in 1776 was named King George III’s official surgeon. Hunter had gained fame for his studies of anatomy, which led to his pioneering a scientific approach to surgical procedures and treatments.

Of course, learning and advancing his trade was no simple task. At times, it was quite ghastly. Gaining new knowledge came through the dissection of thousands of cadavers. These bodies were dug up from their fresh graves by resurrection men and delivered to the back door of Hunter’s home late at night. This gruesome nightlife, paired with respectability during the daytime hours, is believed to be the inspiration for Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

During his years of research he had also amassed an enormous collection of oddities and specimens. According to the Royal College of Surgeons website, it included “nearly 14,000 preparations of more than 500 different species of plants and animals.” These were all on display in his private museum in Leicester Square.

But despite the thousands of preserved body parts and organisms, it was missing one thing: the body of a giant.

And Byrne knew it.

In fact, according to Wendy Moore, author of The Knife Man, “Almost all of London knew of [Hunter’s] obsession with attaining the giant’s corpse. And there were others in the running, too.”

As the Irish Giant’s health began to decline, due to tuberculosis and alcoholism, he feared his body would be acquired by Hunter or another curious surgeon. So he took precautions. Byrne arranged to have his body placed in a lead coffin and buried at sea, ensuring he would escape Hunter or any other body snatcher wishing to dig him up.But Hunter wasn’t to be denied so easily. When Byrne died in 1783, at the age of 22, the wealthy doctor simply bribed a member of the funeral party, reportedly as much as £500, to keep the giant’s body. Rocks filled the coffin to match Byrne’s weight and fool anyone else involved with the interment.

Having acquired his prize, Hunter snuck it home, shielded by the darkness of night. As Moore writes, “He hurriedly chopped the Goliath into pieces, threw the chunks into his immense copper vat, and boiled the lot down into a jumble of gigantic bones. After skimming the fat out of the cauldron, Hunter deftly reassembled the pile of bones to create Byrne’s awesome skeleton.”

The only problem for Hunter was that his secret stash of bones had to remain a secret. Four years passed before Hunter shared news of his acquisition with a friend.

The skeleton can still be seen today at the Hunterian Museum in London, along with the rest of his unusual collection.

![John Hunter by John Jackson. John Jackson [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.](http://www.weirdhistorian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/John-Hunter-by-John-Jackson.-John-Jackson-Public-domain-via-Wikimedia-Commons..jpg)