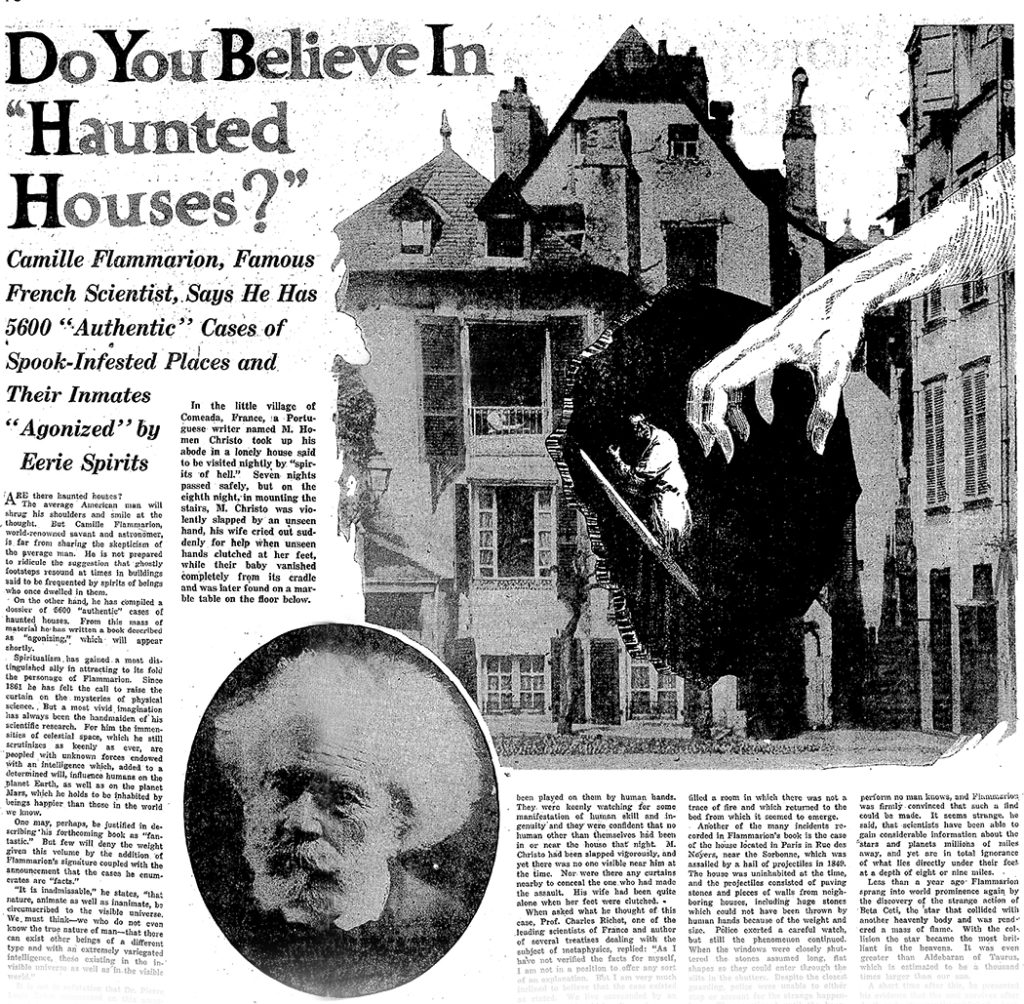

A review of Haunted Houses from The Sun, January 27, 1924.

French astronomer Camille Flammarion wrote numerous books on the stars and the celestial bodies within them, starting with La pluralité des mondes habités (The Plurality of Inhabited Worlds) in 1862. He was a big believer in extraterrestrial life—and life after death.

Flammarion felt that there was much more to the world than our senses could experience.

“It is inadmissible that nature, animate as well as inanimate, be circumscribed to the visible universe,” he said. “We must think—we who do not even know the true nature of man—that there can exist other beings of a different type and with an extremely variegated intelligence, these existing in the invisible universe as well as in the visible world.”

These beings could be spiritual or alien. Of the latter, he wrote much of Martians, convinced that they were of superior intelligence and living better lives.

“You can be sure we shall correspond with the Martians someday,” Flammarion promised. “H.G. Wells has predicted this with rather burlesque fantasy, but we will not utilize machines, we will make use of psychic currents in which I firmly believe telepathic power is stronger than space.”

As for the spiritual, he became convinced the soul lived on after death and began collecting tales of ghosts that haunted houses and spoke to loved ones left behind.

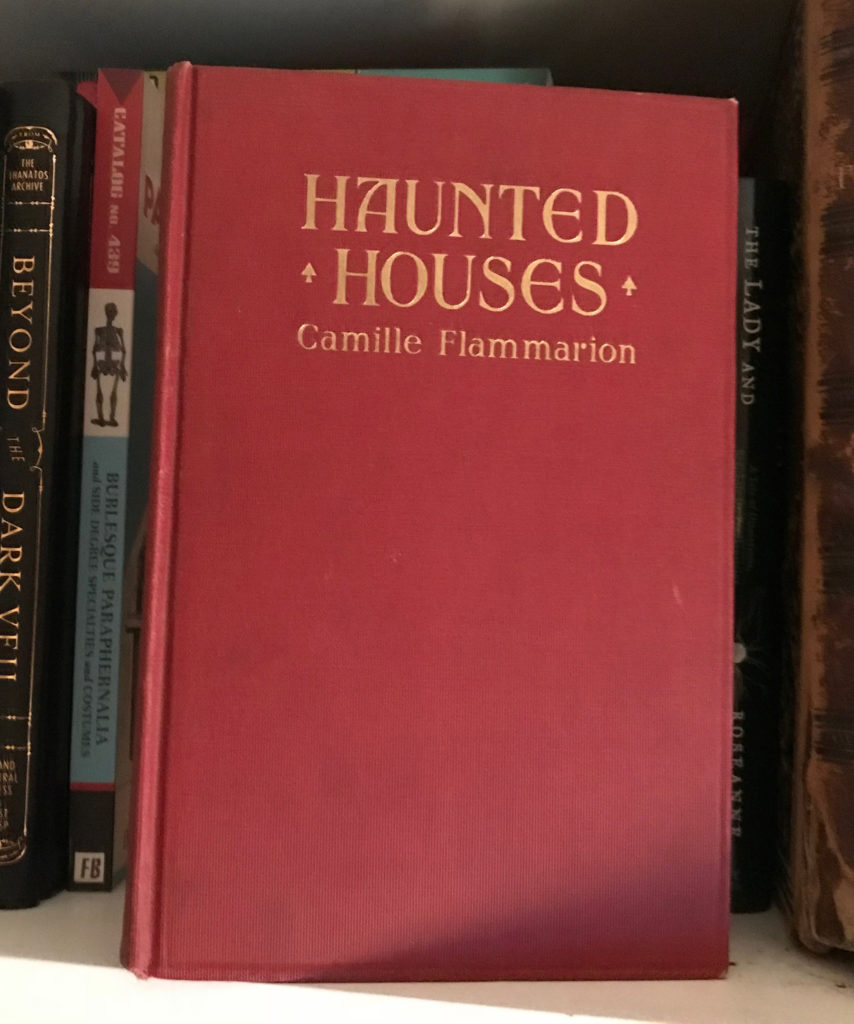

In his 1924 book, Haunted Houses, he shared stories from 5,600 “authentic” cases shared with him through letters and diary entries. One such letter recounted the story of a spirit making contact at the moment of death:

I was married on July 4, 1888. My sister, aged fifteen, on the day of my wedding, as she was able to be present had been seriously ill, but was better, if not quite recovered, at all the festivities.

On July 6 my wife and I left for our honeymoon, and my sister saw us off.

We therefore went away happy, be it noted, and without any fear to trouble us during our journey.

Haunted Houses, by Camille Flammarion (1924).

The letters which we received from our relatives between July 6 and July 12 showed no sign whatever of any anxiety with regard to my sister. The 12th of July (we were then in Paris) was, for me and my wife, a delightful day, up to ten o’clock at night. We spend the evening at the Châtelet Theatre. At ten o’clock I became preoccupied and filled with a great sadness. My young wife could not understand this sudden change in me; neither could I, for that matter. On leaving the theatre I hurried her back to the hotel where we were staying—Hôtel d’Espagne, cité Bergère.

Still gloomy, my wife having gone to bed, I went also. I put out the candle and remained in bed with my eyes open, silent, puzzled by my own condition. It must then have been about one o’clock.

Suddenly there was a crash, a terrible noise, in the room. My companion cried out, alarmed and frightened. I lit the candle. The door of the wardrobe was open. We had not touched it, and it was empty. I calmed my wife, shut the wardrobe door and got back to bed, quite myself again.

Next morning, on rising, we received a telegram recalling us to Marseillan (Hérault); my sister had died the day before at ten o’clock. She knew that we were at the Hôtel d’Espagne.

Had her last thought been for us, and had she transmitted it to us where we were? We could only receive it at the Hôtel d’Espagne.

There is no need for me to assure you of the absolute truth of this story.

I have since had other and very great troubles and everything has remained quiet. Those whom I loved and who are no more no longer communicate with me. Do they see my tears and my suffering? I could wish they did.

Believe me, etc.,

Etienne Mimard

The book’s collection of ghosts included many mischievous ones. They laughed, slapped people, grabbed feet, spilled coffee, cracked china, tapped walls, dripped blood, filled rooms with smoke, and threw rocks.

Flammarion claimed the cases had been carefully investigated and came from reputable sources. Still, he acknowledged there had been cases of fraud, like the houses that had been “haunted” by pranksters wishing to lower the value of homes before buying them.

But those are no fun.