“You don’t believe in me,” observed the Ghost.

“I don’t,” said Scrooge.

“What evidence would you have of my reality, beyond that of your senses?”

“I don’t know,” said Scrooge.

“Why do you doubt your senses?”

“Because,” said Scrooge, “a little thing affects them. A slight disorder of the stomach makes them cheats. You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of an underdone potato. There’s more of gravy than of grave about you, whatever you are!”

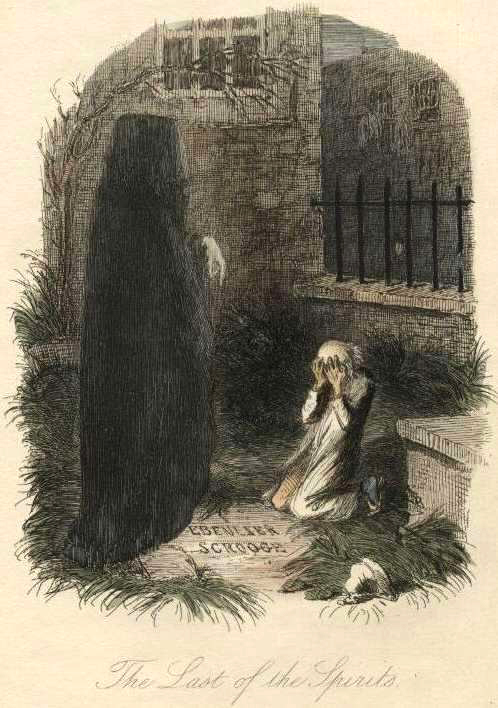

– A Christmas Carol, by Charles Dickens, 1843.

Living in nineteenth-century London, Charles Dickens was knee-deep in the local fervor for spirits and séances. His frequent writings about ghosts, however, were influenced by tales he heard long before they were in Victorian vogue. At an age even younger than Oliver Twist, Dickens’s nanny filled his head with ghastly fodder for future tales.

“The first diabolical character who intruded himself on my peaceful youth was a certain Captain Murderer,” Dickens wrote, reflecting on his childhood. He described the Captain as a man on a mission to marry wealthy, then eat his “tender” bride. In one of the hundreds of times he heard versions of the tale, the character found a wife, then “cut her head off, and chopped her in pieces, and peppered her, and salted her, and put her in the pie, and sent it to the baker’s, and ate it all, and picked the bones.”

With each telling, the nanny began by uttering a low creepy groan and clawing menacingly at the air. The more she terrified young Charles, the more she enjoyed herself.

“So acutely did I suffer from this ceremony in combination with this infernal Captain, that I sometimes used to plead I thought I was hardly strong enough and old enough to hear the story again just yet,” Dickens recalled. “But, she never spared me one word of it. … Her name was Mercy, though she had none on me.”

Dickens’s imagination was off and running. Away from Miss Mercy, he delighted in reading ghost stories in penny dreadfuls and, years after A Christmas Carol, published ghost stories in his own magazine, All the Year Round. But Dickens always separated his fiction with what so many around him took for fact. In John Forster’s 1874 biography, he said, “such was his interest generally in things supernatural, that, but for the strong restraining power of his common sense, he might have fallen into the follies of spiritualism.”

Rather than fall for mediums’ abilities, he sparred with them and exposed their tricks whenever possible. And he did so as one of the early members of the London Ghost Club, founded in 1862.

Following Dickens’s death in 1870, according to some he became a ghost and spoke to Spiritualists from the beyond. Just a few years later he allegedly spelled out his name on a Oujia board and letter by letter told one of the sitters, an aspiring writer, to meet with his son, Charles Dickens Jr. The next day the man took the spirit’s advice and visited Junior, an editor of a publication called Household Words. Dickens’s son met with him, gave him a job, and the young man embarked on a thirty-year career in journalism.

In 1873, a Vermont-based medium and printer, Thomas Power James, told reporters he’d never read Dickens yet claimed to be taking dictation from the writer’s ghost in order to complete the manuscript to his final work, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Writing eight to ten pages at a sitting, three times a week, the medium projected the book would be completed within six months. Locals who’d perused the medium’s transcriptions felt assured the work was genuinely Dickens’s. One said the words were “so unmistakably Dickens’s style that no one not blind with prejudice would doubt it.” Though many writers (among the living) have tried to complete Drood, it remains unfinished.

Other Spiritualists believed Dickens possessed the gift of mediumship during life and took notes from ghosts as he wrote. In 1882, The Medium and Daybreak picked up a quote from the editor of the Fortnightly Weekly in which he said, “Dickens once declared to me that every word he said by his characters was distinctly heard by him.” The Spiritualist newspaper added a statement from another, James T. Fields, claiming, “Dickens was at one time so taken possession of by the characters of whom he was writing, that they followed him everywhere, and would not let him alone for a moment.”

Did Dickens really hear ghosts and become one himself? Or were those who believed it just striving to be as imaginative as the famed author?

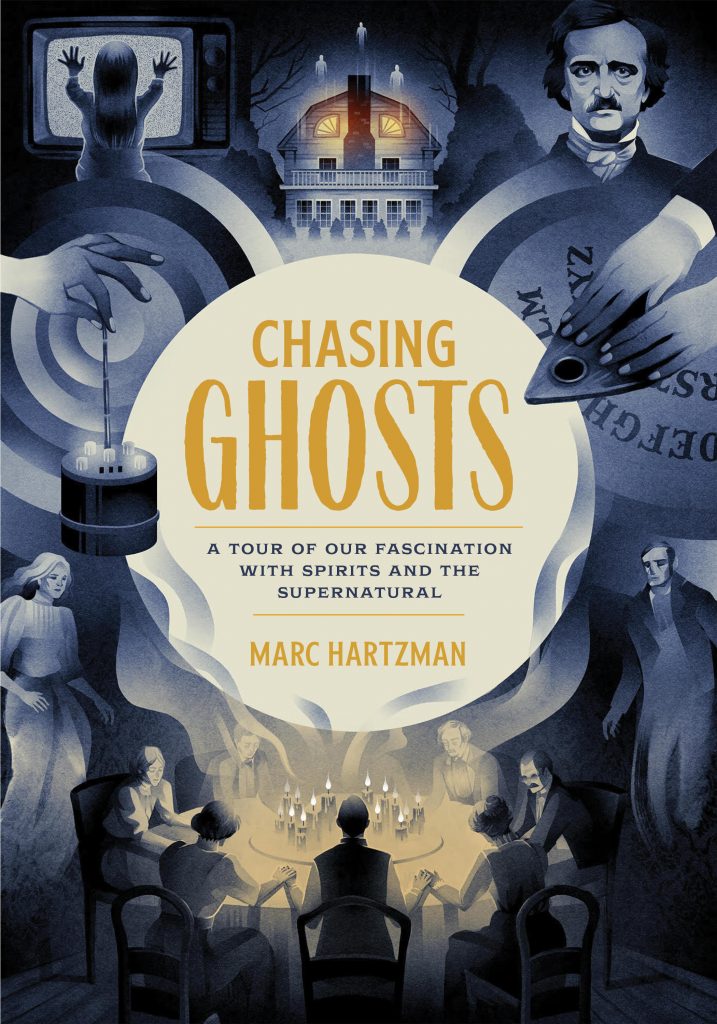

This piece was originally written for Chasing Ghosts, but was cut for space. Buy a copy to read more about ghosts and the paranormal.