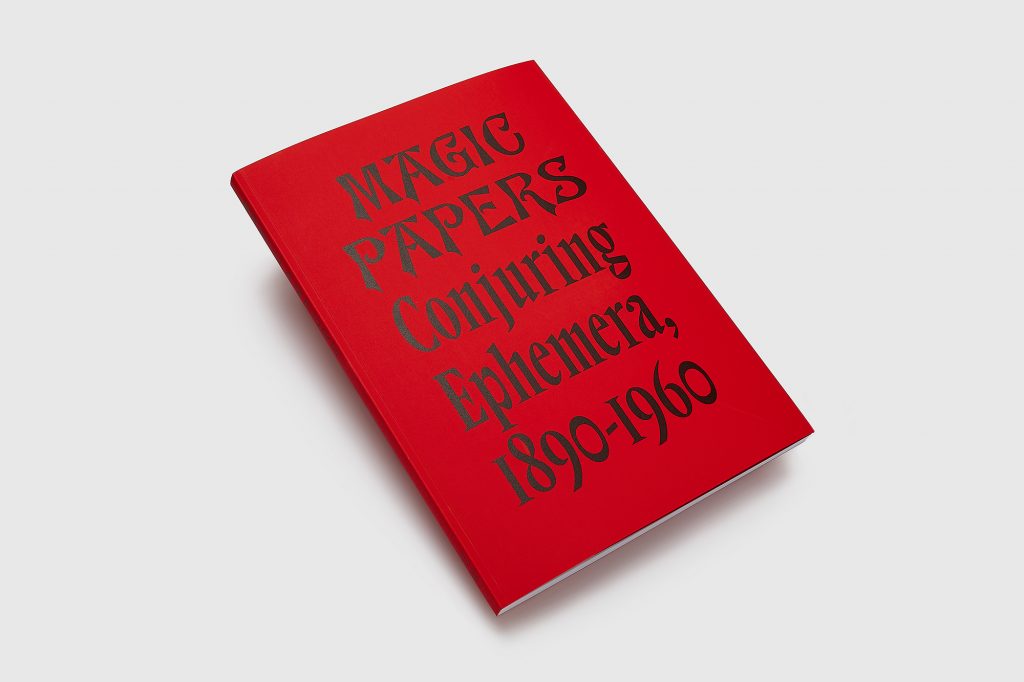

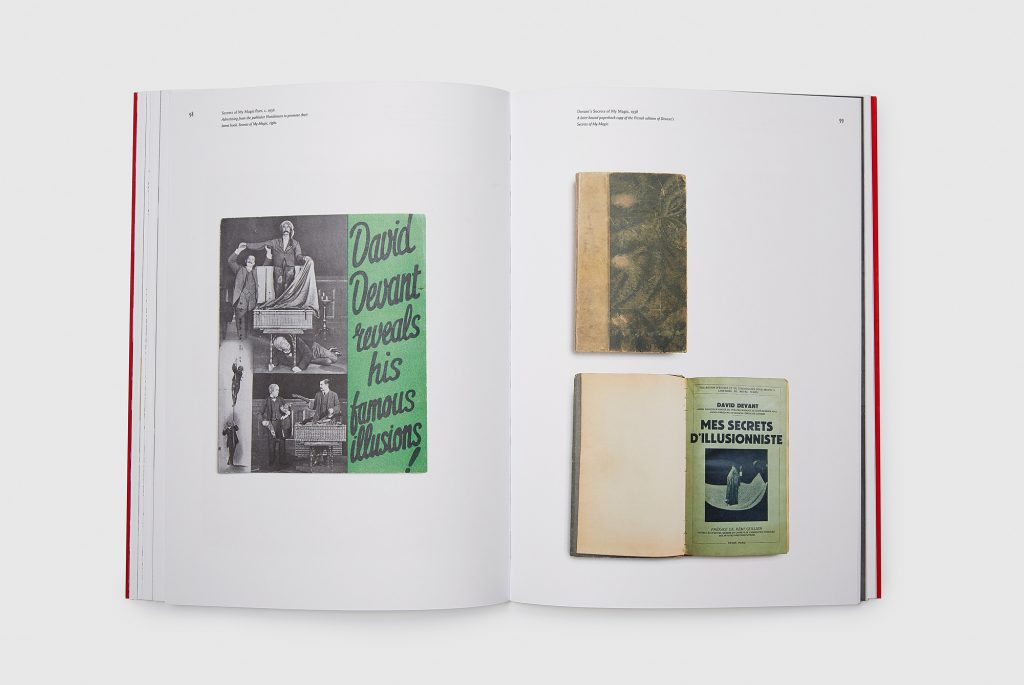

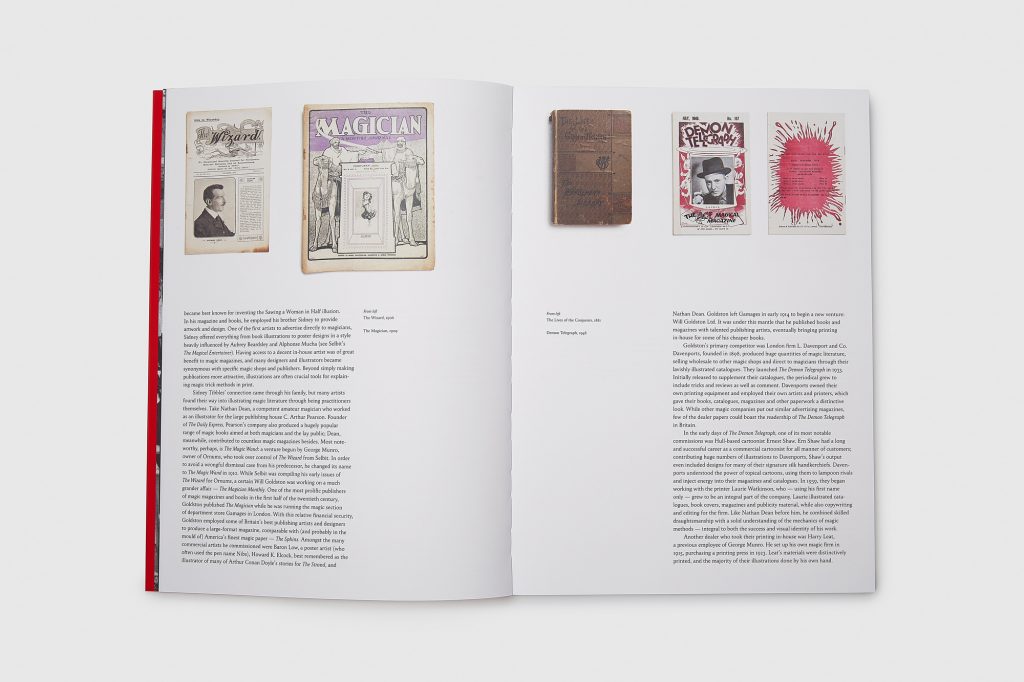

When Philip David Treece’s new book, Magic Papers: Conjuring Ephemera, 1890-1960, arrived from his London-based publisher, CentreCentre, I was both relieved and overjoyed. Relieved because it made the journey across the Atlantic during the pandemic, when mail has been especially slow and spotty. And overjoyed because the publication is absolutely beautiful. It’s the kind of book that truly excites the senses, from the gritty texture of the cover stock to the fresh aroma of the printing to the beautiful full-color imagery of magic ephemera gracing its 144 pages.

Magic Papers takes advantage of its spacious 13.3” x 9.5” format to celebrate journals, periodicals, books and other ephemera created for the magic community from the heyday of conjuring design. It includes a 16-page gloss insert featuring a collection of magical apparatus.

Every piece showcased in the book comes from the author’s personal collection, some of which can be seen at collectingmagic.co.uk. Read my interview with Philip David Treece below, and order Magic Papers here before it vanishes—only 800 copies have been printed.

How long have you been collecting magic books and ephemera, and what got you started? How have you gone about acquiring pieces (particularly before the ease of eBay)?

Around seventeen or eighteen years, I think. I’ve been into magic for over twenty-five years, but I don’t think I was consciously collecting until my early teens.

I started magic the same way as most people of my age in the UK. There was a fantastic long-running TV show called The Paul Daniels Magic Show. I loved it as a toddler and received a Paul Daniels magic set for my fourth birthday.

I do use eBay, but my best finds have always been made in person, generally at antique fairs, book shops or general auctions. I’ve also been lucky to receive gifts from friends who share my interest. eBay and specialist magic auctions are great ways to find items of obvious collectible value, but obscure books and more ephemeral objects don’t generally appear on those platforms (or are well hidden on eBay). The most important thing to build a broad collection is to read across the subject as much as possible so you know what you’re looking for and be very patient. I also look for items that will be useful for research, rather than have high financial value. A 1920s magic catalogue from an unrecorded company might only be worth a few pounds, but it holds much more information than a Houdini autograph on a scrap of paper worth hundreds.

What sparked the idea for writing Magic Papers? And how did you narrow down your collection and decide what to include?

The idea was Patrick Fry’s, he runs CentreCentre. He publishes books that look at unusual and unrecorded collections. He found my blog (CollectingMagic.co.uk) and contacted me about the possibility of producing a magic related book. After spending a day looking across my collection, Patrick decided a book looking at magical literature would be worth producing.

We then sorted through pretty much everything, looking for the most visually interesting and relevant items to tell the story of magic publishing.

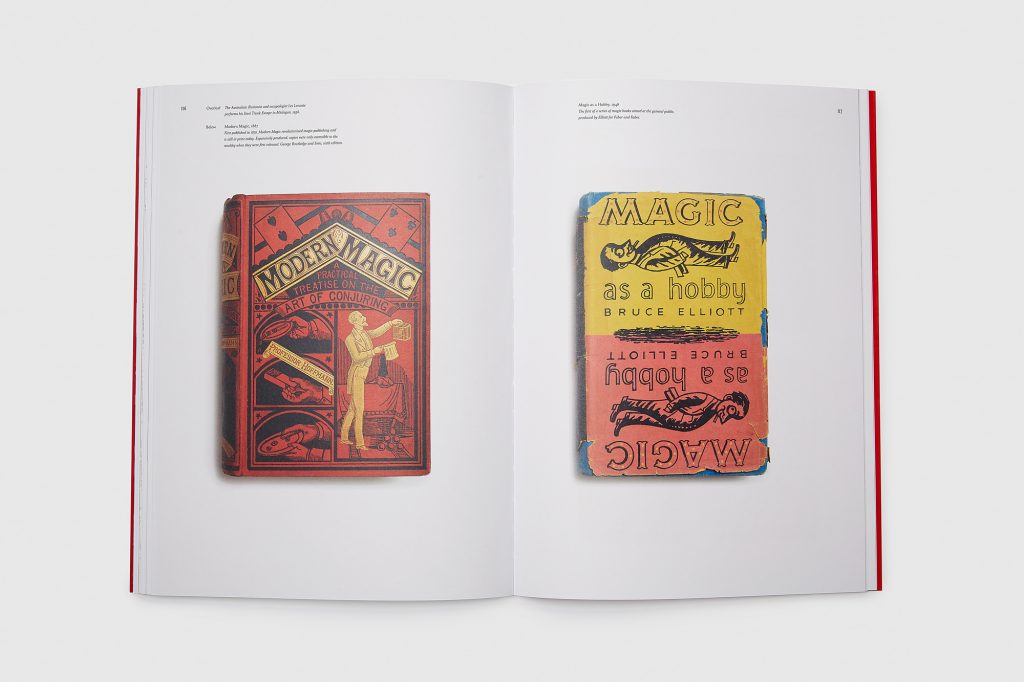

The publication of Modern Magic in 1876 really changed things. It was like the YouTube of its day. How much did it help and/or hurt magicians at that time?

I think it helped magicians and would-be magicians of the time enormously. It was the first English language magic book to truly teach how to perform magic effects, rather than just curtly expose secrets. I’d perhaps argue that its main influence came a few years after its first publication when it was chopped up into smaller sections that were sold as affordable paperbacks. This really put learning magic into the hands of a much wider audience. Much of his writing was later plagiarised and sold in even cheaper formats.

I’m sure some magicians at the time were upset that secrets were publicly available, but the magic community soon embraced Hoffmann. His work is still really relevant to magicians today, which is why I’m happy to say my book site, CollectingMagicBooks.com, is republishing them this year (apologies for the shameless plug).

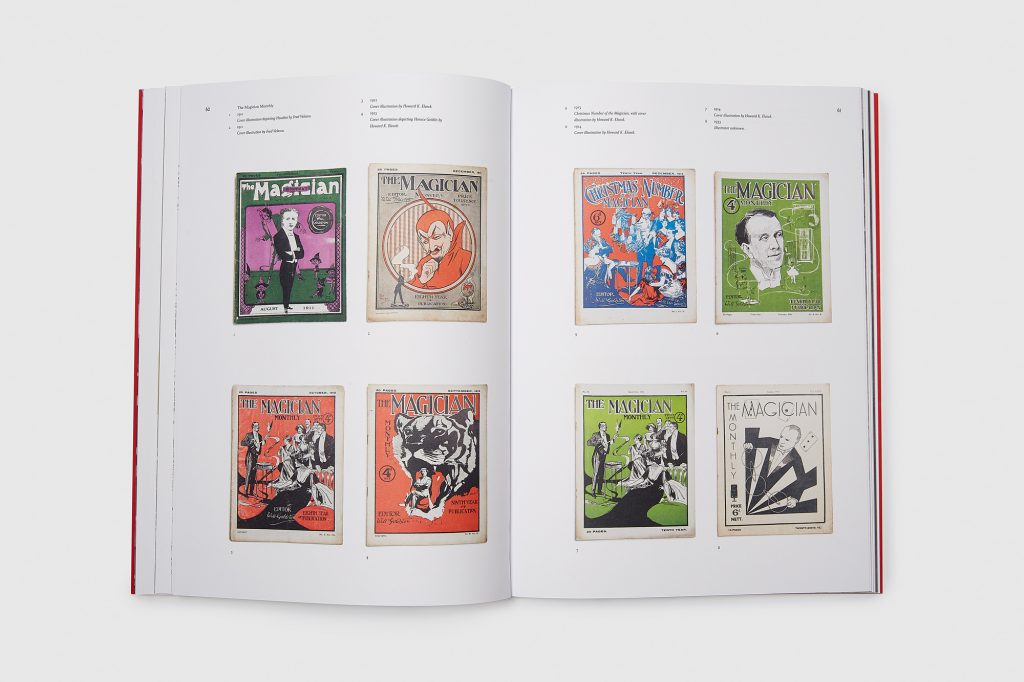

I love the design of old magic books, pamphlets, posters—even letterhead from magicians. How critical was design back then, and why don’t we see the craftsmanship as much anymore?

I think it was very important, but priorities have changed. In the period covered by Magic Papers the primary way magicians learned magic, bought tricks and kept up to date with magic news was through printed matter. There was also good money to be made in conjuring books and magazines, by magicians and magic shops, so original design was an essential part of competing in a busy market place.

Today magic magazines are few and far between and many great magicians teach their creations through video downloads rather than books. Similarly, magic manufacturers and shops spend their advertising money creating online content to show off tricks. I think there’s still a great deal of skilled work being done promoting magic and magic tricks, it’s just moved away from printed matter towards more digital media. There are still beautiful magic books and periodicals being produced though, they’re just no longer read by the majority of magicians.

How much magic have you learned from your collection? Do you perform as well as collect?

I’ve learned a great deal from it. I’m always reading as much as I can and learning how apparatus work in practice is often useful when researching the history of magicians and magic firms.

I perform for myself and a few close friends occasionally. I used to perform a lot more but, as I got older, I realised it wasn’t really in my character, and I didn’t particularly enjoy performing publicly anymore. If people hear you’re a magician they want to see a trick right away, some magicians relish that chance to show off their skills, but it’s not for me. I still love performing to friends when the circumstances are right though.

In your introduction, you mention that magic is a very solitary art. Do you expect we may see a few more magicians after this world comes out of quarantine?

I hope so. It’s been a very hard time for professional magicians, who’ve lost most of their work, but one small solace is that they have the perfect hobby for quarantine.

I imagine there will be some new magicians emerging too. It’s a hugely rewarding pastime, I’d recommend it to anyone.

If you had to pick one book, which would be your favorite, and why?

That’s a very hard question. I think, of the books in Magic Papers, it might have to be Greater Magic by John Northern Hilliard. It’s practically an encyclopedia of magic tricks. The effects are thoroughly described and illustrated though, so it is a truly practical book. It’s also handy as a doorstop.

![Toby The Sapient Pig, 1817 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.weirdhistorian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Tobythesapientpig-1871-crop-235x190.jpg)