Today, September 3rd, marks the 360th anniversary of Oliver Cromwell‘s death. The Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland was embalmed and buried in Westminster Abbey.

Three years later, Charles II restored the monarchy and exhumed Cromwell’s body. He wanted to punish Cromwell posthumously for the beheading of his father, Charles I, in 1649. Before a large public gathering, Charles hanged Cromwell’s lifeless body, then beheaded it and placed the head on a spike atop Westminster Hall.

The embalmed head stayed there as a deterrent to anyone else who might wish to mess with the monarchy. It gazed over London for about 25 years, until a storm knocked it off. A sentry picked it up and took it home. From there, Cromwell’s head journeyed through England until it was reburied in 1960—three hundred years later.

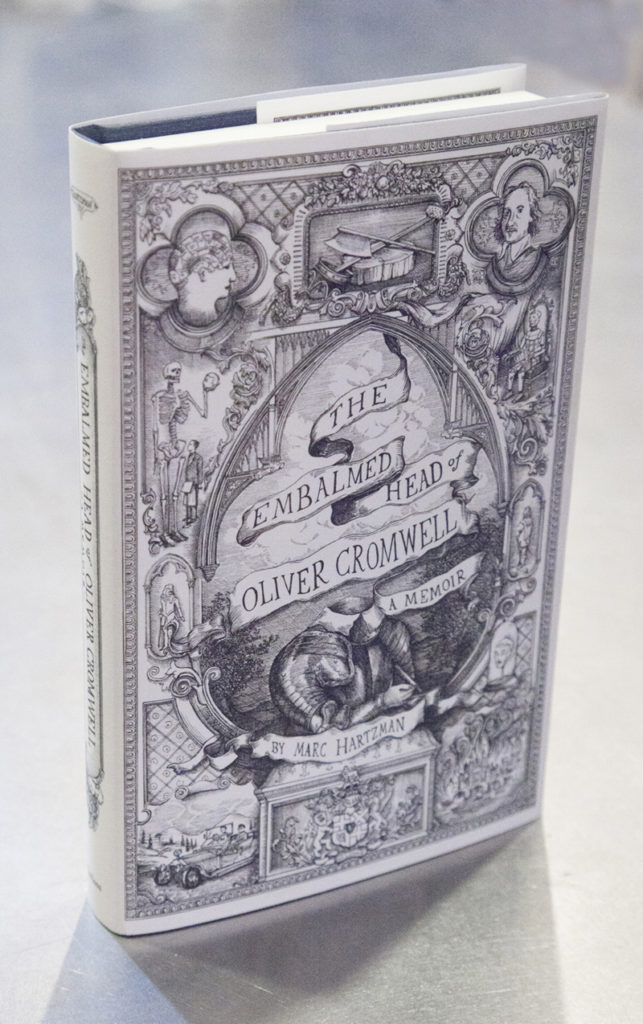

My book, The Embalmed Head of Oliver Cromwell: A Memoir, tells the story from the head’s point of view. Below is an excerpt about the moment of death, on that September 3rd day in 1658.

Death is, without question, the worst part of life. A moment that strikes fear in our innermost thoughts, regardless of how strong, powerful or confident our exteriors appear. When one considers his own death, there is nothing but the certainty of leaving all behind, and the uncertainty of what, if anything, lies beyond. Worse still is the one thing that we do know awaits—

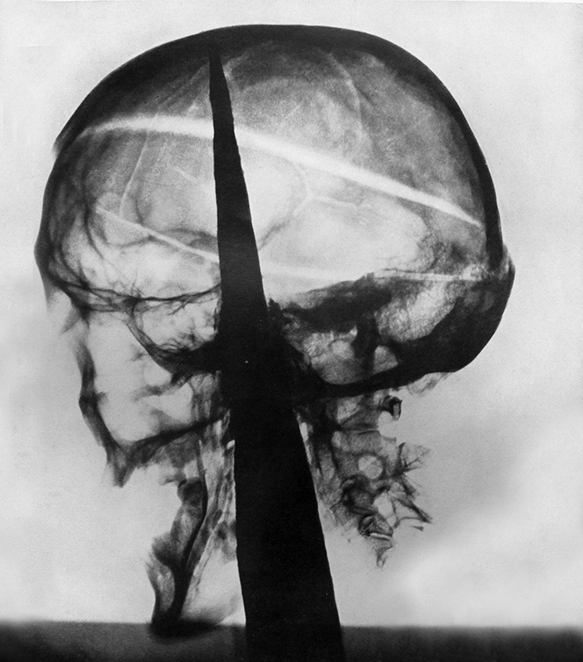

X-ray of Cromwell’s head showing the iron spike from Westminster Hall.

burial. Eternity is six feet below the earth’s surface, immobile in a small box offering but a thin, penetrable barrier from soil and the subterranean creatures that prey upon the vulnerable flesh of the dead. These are the angels that return us to the dust whence we came. Heaven or Hell we know not, but this much is assured.

This existence does, however, have its varying degrees of wretchedness. Those who achieve greatness, like Myself, avoid plots bevelled into the dirt. As Lord Protector of England, I commanded a more fitting burial, spared from the elements in the hallowed confines of Westminster Abbey. Within its sacred walls, the dead are never forgotten and achieve a form of immortality.

It is here that my afterlife story truly begins. I lay buried in an east-end vault of Henry the VII’s chapel, just behind the king’s gaudy tomb, where his bones resided next to those of his wife, Elizabeth of York. Carved images of saints and a spirited dragon covered Henry’s crypt. I required nothing so fanciful, though I had oft admired this chapel’s space for its architectural magnificence, particularly its stone fan-vaulted ceiling prodigiously embellished with carved pendants and pewter emblems. Clerestory windows give entrance to the sun’s light and feathered mouldings and sunk panels robustly cover the side walls. It was a fine place to rest.

The Embalmed Head of Oliver Cromwell: A Memoir, by Marc Hartzman

The day after my death, on the 4th of September, 1658, my physician, Dr. George Bate, had sliced open my chilled corpse to investigate the cause. Bate was a knowledgeable man of fifty years with a broad moustache, curled locks and firm hands who had aided Charles I during his reign.1 Before resting my eyes forevermore, I told those attending me to go on cheerfully, and repeatedly praised God from my deathbed, muttering, ‘Truly God is good, indeed He is, He will not leave me.’ I was at peace, for I had been in Grace. Dr. Bate had done all that the ancient teachings from Galen and Hippocrates offered, yet the Lord was not to be denied; it was my time. Now Bate sought answers as he shifted my organs with invasive fingers. His bloodied hands finally uncovered disease in several locations, particularly my spleen. A bout of malarial fever and kidney trouble had previously been deemed the main culprits in my passing, but surely damaged innards offered little help. I also suspected my internal defences had weakened after my anguish over the death of my second daughter, Bettie, just a month prior. She had taken ill in June, partly because of the death of her youngest son, Oliver, who lived but a year. Doctors claimed she had an inward imposthume of the loins, but they lacked the knowledge to properly treat her. I fought my emotions in her presence, hoping to hide my sadness and fear and give her strength through my confident exterior. She, too, struggled to appear optimistic, so as to mitigate my worry. Yet our close relationship made such feigned dispositions entirely futile. When her life at last slipped away, the shock overwhelmed my being and I collapsed to the ground, motionless for days. Though they were not visible to Dr. Bate during his examination, my heart suffered deep wounds as well.

Books are available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble and other online booksellers. Or directly through me.