Uri Geller made a career of bending spoons with his mind and countless psychics have claimed to be able to see the future. But one of the most unusual assertions of mental powers came from Ted Serios—a Thoughtographer.

It was the mid 1960s when Serios began sharing his ability to project his thoughts onto a piece of film. Yes, he could think of an image and send it into a camera. He called them “thoughtographs.” This was typically done with Polaroid cameras.

![Ted Serios, [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.weirdhistorian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Ted_Serios_1.png)

Ted Serios, [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

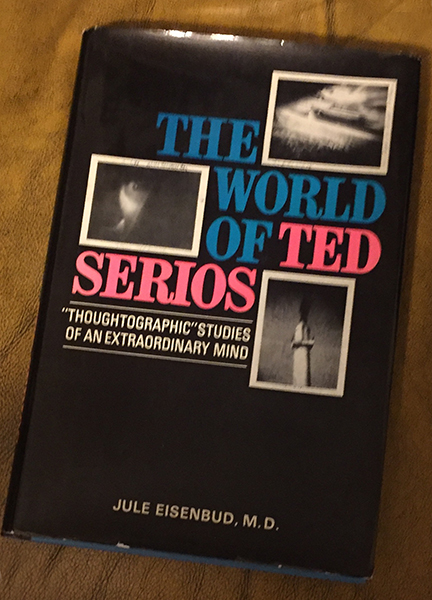

Eisenbud put Serios through two years of extensive testing and came to fully believe in his subject’s abilities, as he explains in his 1967 book, The World of Ted Serios: “Thoughtographic” Studies of an Extraordinary Mind.

Serios didn’t produce images with every attempt, but each was an spirited experience. As Eisenbud described it:

When about to shoot, he seemed rapidly to go into a state of intense concentration, with eyes open, lips compressed, and a quite noticeable tension of his muscular system. His limbs would tend to shake somewhat, as if with a slight palsy, and the foot of his crossed leg would sometimes start to jerk up and down a bit convulsively. His face would become suffused and blotchy, the veins standing out on his forehead, his eyes visibly bloodshot.

If you’re having difficulty imagining this, Eisenbud offered this colorful parenthetical to help:

“(The proctologist would perhaps liken what was occurring to the kind of tension and pressure built up during a difficult movement.)”

He also drank a lot of beer and hard liquor during the process.

The tests were reportedly designed prevent the possibility of deception and included various experts in the fields of medicine, physics, chemistry, and psychology.

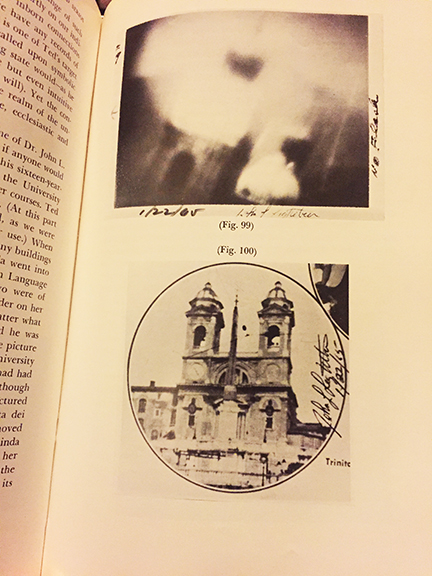

In one of his Thoughtography sessions, Serios asked the attendees to suggest a subject for him to produce. The daughter of the doctor whose home they were in requested a building at the University of Rome, where she planned to take a few courses. She had a folder of images with her, at a distance from Serios. He produced a blurry image which, according to Eisenbud, resembled a Roman church pictured in the girl’s collection.

His images were always blurred versions of something, that is, if they didn’t come out completely white or black. With a creative interpretation, like the Roman church, they could often be judged as successes.

So was Eisenbud right? Was Serios finally living proof of the existence of psychic abilities? Despite Eisenbud’s confidence, many disregarded the Thoughtographer as a charlatan. An article in the October 1967 issue of Popular Photography claimed that Serios inserted an object, possibly a small piece of photographic transparency, into the “gismo” for the lens to capture. In their test, they included two experts Eisenbud hadn’t been using: magicians.

Thoughtograph of a Roman church, which Eisenbud believed matched a real one.

Eisenbud didn’t take too kindly to the claim. He quickly offered a challenge as his response:

“I hereby state that if, before any competent jury of scientific investigators, photographers and conjurers, any chosen by them can in any normal way or combination of ways duplicate under similar conditions, the range of phenomena produced by Ted, I shall (1) abjure all further work with Ted, (2) buy up and publicly burn all available copies of The World of Ted Serios, (3) take a full-page ad in Popular Photography in order to be represented photographically wearing a dunce cap, and (4) spend my spare time for the rest of my life selling door-to-door subscriptions to this amazing magazine. No time limit is stipulated.”

James Randi, aka the Amazing Randi, who has a long history of exposing charlatans, responded to the invitation. However, he was informed that the “similar conditions” meant he’d be “inside a Faraday cage, naked, at a considerable distance from the camera he would never be allowed to touch, (as Serios frequently did) and would have to get roaring drunk beforehand as Serios usually was when he worked.” Randi declined.

The New York Times also found difficulty believing in Serios. In its May 14, 1967, review of the book, it mocked Eisenbud’s experiments, saying that the doctor “seems to have little notion of what experiments are, and less liking for the rigors and methodological niceties of scientific research.”

One observer who attended a test in 1966, Nile Root, agreed with the Popular Photography explanation. He explained his experience and everything wrong with it here. In brief, he described the event as such:

Seven guests assembled the evening I was involved, a typical number for a group to witness a demonstration according to Dr. Eisenbud. Each guest was asked to bring at least five rolls of 3000 speed Polaroid film.

Dozens of exposures were made in the two cameras brought by Dr. Eisenbud. Serios would hold what he called a gismo (a black paper tube about one inch in diameter and one and one half inches long) to the camera lens. He would scream obscenities, contort his face and sometimes yell, ‘now!’ — the signal for whoever was holding the camera to trip the shutter.

He became quite drunk and obnoxious. He was chastised often by Dr. Eisenbud but the doctor still continued to supply beer to Serios.

The frenzy continued. The evening wore on; still no thoughtographs emerged from the multitude of developed images.

Then, amazingly, after five long hours, three strange images arrived (after the one minute to process each exposure). Altogether, with the two cameras, he produced six blurry images unrelated to the room’s environment. I was puzzled.

He often displayed the gismo so we could see that it was empty but in his drunken condition he finally slipped up.

Serios became careless: as he was waving his arms and yelling, I saw a shiny object reflect from inside the paper gismo that he always held to the camera lens.

Dr. Jule Eisenbud’s 1967 book about Thoughtographer, Ted Serios.

Naturally, Serios had always maintained his abilities were genuine. In a Life magazine feature from September of 1967, writer Paul Welch said, “He was a driven man. He had this thing he could do and he wanted someone to explain it to him. He wanted to control it, to consistently predict the pictures he would make (which he can do only occasionally), to make it useful. He thought, for instance, he might be able to spy on Russian missile sites for the Air Force. But above all, he wanted to stop proving he could do it, that he wasn’t a charlatan, that is was for real. ‘If it isn’t for real,’ he would argue, ‘why can’t I do it all the time? If it was a trick I could make money on it. I could go into nightclubs or on the TV.’”

He did make it on TV—on a segment from a 1985 episode of Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers. However, he and Eisenbud were unable to recapture the magic (or magic trick) from their earlier sessions. If they had, and the stunt had been authentic, perhaps, as the Times said in 1967, “our general view of the nature of the universe will certainly require a drastic overhaul.”