Taphophobia is the fear of being buried alive. For centuries, it was an all too common fear—because reports of it happening were all too common.

So great was the worry that in the late 1800s a Society for the Prevention of Premature Burial was formed to help put an end to such horrors.

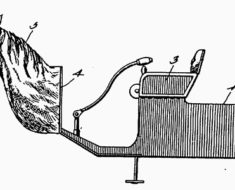

Over the years various entrepreneurs had developed special caskets that offered a means of escape, including one with a chimney box leading to the surface and a place for snacks. Another included an electrical switch which lit a red lamp, rang a bell and waved a flag above ground.

Taphophobia in The Evening Post, Volume CVIII, Issue 84, October 5, 1929

But in 1929, the Society in Belfast, Ireland opted for a solution that would avoid any need to escape from six feet under.

It hoped to build a large mortuary where bodies could lie until it was 100% certain they were dead.

“Eerie tales of people who have been proved to have moved in their coffins have caused such anxiety that many are now leaving instructions that after death —or supposed death—they should be cremated,” stated The Evening Post. “It is felt that premature cremation would be preferable to premature burial, and it is significant that while in 1885 three cremations took place, the total since then has now reached 44,084.”

The secretary of the society, Maxwell Johnson, explained the plan to a reporter:

Attached to each body is a cord connected with a system of bells, which would ring at the slightest movement of the body. Attendants are on duty day and night, and if a bell rings they dash for a doctor. Many nervous people think that nobody should be buried within a week of supposed death. Amazing precautions are sometimes taken by people to make sure that they should not be buried alive. They have ordered that a stiletto should be thrust through them, a vein severed, or that they should be decapitated, or buried at sea.”

The mortuary was compared to the Munich Dead-Houses. A Munich law required every body to be placed in a dead-house at the cemetery for two days before burial.

In the 1839 book, Notes of a Wanderer, author William Fullerton Cumming states that “no stranger should pass through Munich without visiting this establishment.”

During his visit he encountered ten exposed bodies—seven children and three adults—through glass doors.

“It was a sight capable of exciting mingled emotions; but certainly horror would be the predominating feeling in the breast of one unaccustomed to scenes of death,” he wrote.

Cumming described the children as being dressed in white cotton clothes with garlands of flowers around their heads and “pallid faces smiling in death.”

Of the adults, two were dressed in clothing that indicated they were from the upper class. Their coffins laid side by side, perched at an incline. The third, he noted, laid on a plain board without any decoration.

“It was sad to see the distinctions of wealth in the dwellings of the dead!” he observed.

An 1867 article further described the Munich Dead-Houses.

“While thus awaiting interment in the two rooms prepared for the purpose, signal wires are attached to a forefinger of each corpse, which communicate with bells in an office above, where a servitor is always on duty,” the article explained.

If someone should awaken from their apparent death, he or she could ring the bell and be free to head back home. Or, as the reported noted, if the person was ready for death, he or she could stay put.

“If he is satisfied with his position and prospects, I suppose he can decline to ring the bell, turn over and go to sleep again,” he remarked.