Those fond of clichés will surely agree that if a dog is man’s best friend, a talking dog might be man’s BFF. In the early 1900s, a dark brown setter, called Don the Talking Dog, was such a pal. The pooch belonged to a German gamekeeper named Martin Ebers, who lived in a quaint Western Germany village called Theerhutte, near Hamburg. But his voice attracted the world’s ear.

News of Don came in 1910, after an American newspaper article claiming Alexander Graham Bell had trained his terrier to speak. Germans didn’t think much of the article — at the time there was a belief that anything was possible in America. But rather than let America have the glory of a talking dog, Ebers’ nephew brought media attention to his uncle’s wondrous companion. Suddenly, the small village was bustling with curiosity seekers and reporters wishing to see if Ebers’ dog was the real deal.

Even skeptics became believers after meeting Don. In describing a conversation with the dog, one newspaper claimed, “The tone was not a bark or growl, but distinct speech.” Another correspondent wrote, “The dog is an unqualified scientific marvel.”

Don the Talking Dog makes headlines, this one being from the New York Times.

Don reportedly began speaking on his own accord in 1905, at the age of six months. As one might expect with a dog, his first words were in regard to food. While the family was eating dinner one evening, Don, like any dog, waited beside the table begging for scraps. His master asked if he wanted something, and Don responded “Haben! Haben!” (Want! Want!). Ebers asked the question again, disbelieving his own ears. Sure enough, Don said “Haben! Haben!”

The dog’s vocabulary soon expanded to other areas in the food department with “hunger” and “kuchen” (cakes). He also pronounced “ja” (yes) and “nein” (no), allowing Don to express his feelings, such as a dislike for cold, wet weather. The clever canine even learned to form a rudimentary sentence with his small arsenal of words. If asked how he was doing, Don could have responded, “Hunger, want cakes.”

The four-legged phenomenon soon attracted the attention of Karl Hagenbeck, the famed German animal trainer and circus founder, as well as other circus showmen and music hall managers. Hagenbeck offered Ebers $2,500 to exhibit Don in his outdoor menagerie at Hamburg. Another impresario offered Ebers $15,000 to purchase the extraordinary dog.

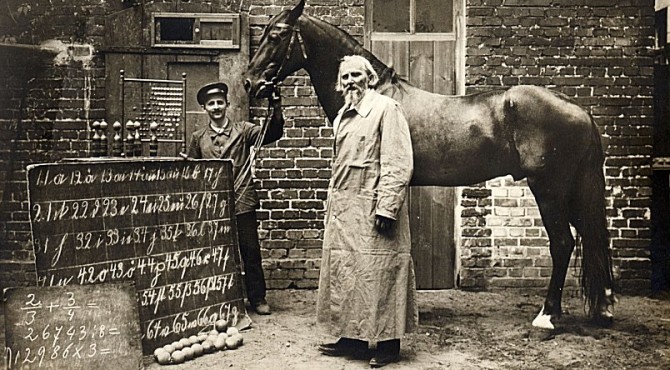

While showmen and the general public were enamored with Don, psychologist Oskar Pfungst was not. In 1912, having debunked an educated horse called Clever Hans several years earlier, Pfungst took it upon himself to explain Don’s garrulous nature. He visited Don and recorded his “speech” on a phonograph. He concluded that the dog merely responded to questions with noises the way any dog might, but through the power of suggestion, listeners heard what they were expecting to hear. A similar experience occurred in more recent years with a dog crooning “I love you” on a David Letterman Stupid Pet Tricks segment. And on YouTube, more than 8,000 videos can be found on dogs allegedly professing their love.

Upon hearing of Pfungst’s findings, The New York Evening Post reported: “It begins to look as if there really were a rather sharp limit to animal intelligence.” As with Hans, Pfungst once again burst an optimistic society’s bubble.

© Marc Hartzman

![Lady Wonder - By Francis Wickware (Dr. Rhine and ESP. Life Magazine. April. 15, 1940) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.weirdhistorian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Lady_Wonder_Horse-By-Francis-Wickware-Dr.-Rhine-and-ESP.-Life-Magazine.-April.-15-1940-Public-domain-via-Wikimedia-Commons-235x190.png)