If anyone ever said you were running around like a chicken with its head cut off, they may have been referring to Mike. Mike the Headless Chicken lost his head in 1945. And then ran around. His owner, a farmer named Lloyd Olsen in Fruita, Colorado, fetched Mike from the yard that fateful day with the intent of turning him into dinner.

But when he swung the axe, the blade missed the jugular vein and left the brain stem in place. A blood clot prevented him from bleeding to death. The head was gone, but the brain stem kept him functioning, so Mike could still strut and peck for food. Rather than swing again, Olsen kept the chicken alive by feeding it liquids and grains through an eyedropper.

Mike soon became a national phenomenon, touring the country in sideshows and being featured in Time and Life. He lived this way for 18 months, until he reportedly choked to death.

Fruita, Colorado celebrates its famous fowl resident with an annual Mike the Headless Chicken Day. Events include a 5k race and a Peep-eating contest. This June marks the festival’s 20th anniversary. “It’s a way to celebrate and educate Fruitians about its unique history,” Tom Casal, Recreation Superintendent, told Weird Historian.

While Mike was an unintended headless chicken, other chickens lost their heads in planned experiments.

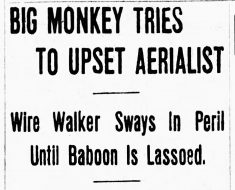

An 1883 article describes a case of a doctor creating a headless rooster to prove it was possible. As he told a Whig reporter, who saw him applying chloroform to a rooster at a hospital, “I am going to show that both politicians and roosters without heads can live in this free country.”

As the story describes, the physician then proved his case:

“The doctor went to work carefully with his fine instruments and took off the bird’s head just above the ears, and cautiously gathered up the muscles, arteries and veins, and applied chemicals to prevent the flow of blood. Into the neck of the biped he placed a glass tube — a channel through which to introduce food into the craw—and then put the bird into a box covered with cloth, with a hole in the centre for the headless neck to go through. ‘In a few hours,’ the doctor said, ‘this chicken will walk around with steady step, a brainless agent without sight, thought or feeling.’”

Sure enough, it did.

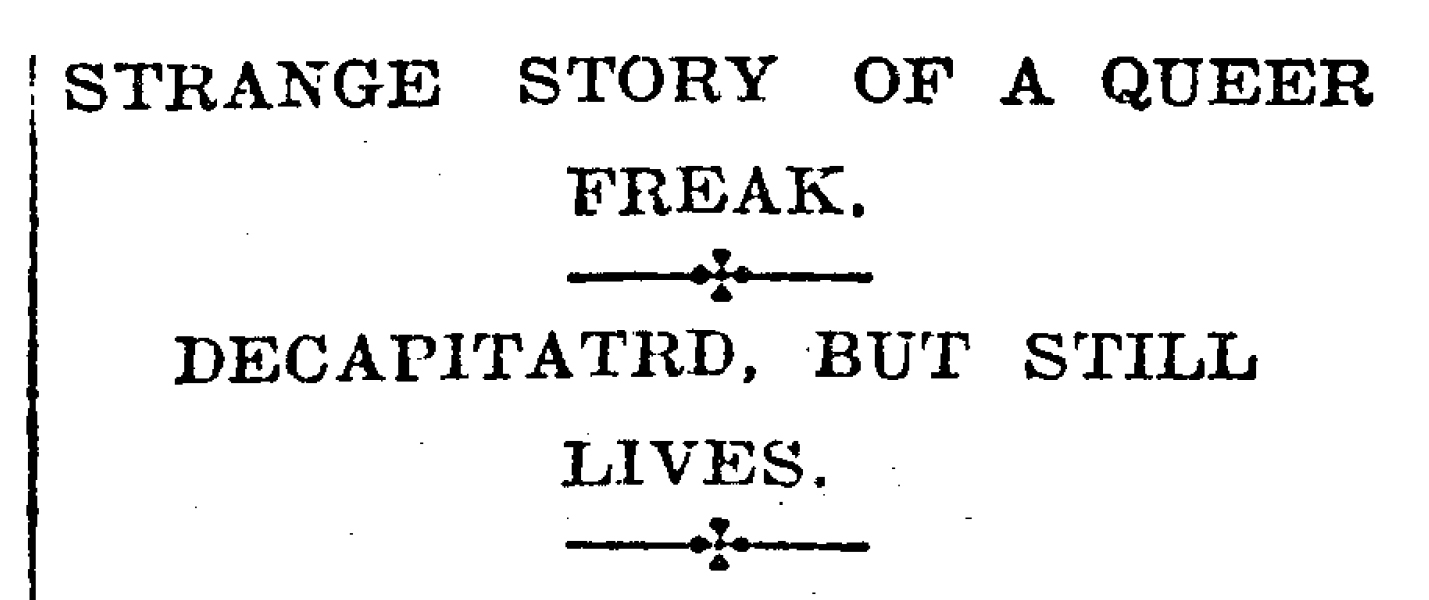

Shortly after, in 1906, a story similar to Mike’s was reported. This one involved a rooster owned by a Mr. L. P. Quivey. Quivey’s story, as he told it to the paper, follows:

You see, the day before Thanksgiving I was killing 50 or more fowl for sale, an’ as I chopped off their heads on the block I threw the bodies into a barrel nearby, When I had killed them all I went to heat some water, intending to scald off the feathers. I was gone an hour or so, and p’raps I wasn’t surprised when I came back to find this ‘ere I rooster without his head, sitting upon the edge of the barrel, bleeding a little from the wound, but not much.

“He was a-poking his headless neck one way and the other as if he was surprised at what had happened, an’ well he might be. I was so surprised myself that I put him down on the floor in a corner, thinking that now his head was off he could not suffer any, and it would not do any harm if I waited to see how long he would live.

“At night he was still alive, and I waited until next morning. When I went out in the morning there he was, big as life, walking around the stable floor in a dazed sort of way, trying to find something to eat. He was making little pecks at the floor with the stump of his neck as though he thought he could pick up corn.

“I nearly dropped dead. The wound seemed to be healing. It had stopped bleeding, and I could see that the brain, top of the skull, an’ all the head fixings were gone— I cut clean off right where the head joins the neck, with perhaps the little mite of the back of the skull left. After watching his pathetic efforts to pick up corn I sort of took pity on him, an’, taking him in my arms, poked a handful of corn, kernel by kernel, down his windpipe, or, rather, gullet. It went inter his crop all right, and he swallowed like a good one.

“Well, sir, that’s the whole story, except that the news of it got abroad an’ folks began coming here, an’ all the doctors in the country came. Dr. Wicks offered ter cure him up, an’ he’s treating him now. Says he will get well. We give him a little soup every day, a little corn, and let him exercise. And, do you know, the fellow is actually trying to crow! It is a fact. Every morning when I come out here he is making queer noises with his throat.”

A doctor named J. P. McElroy, who witnessed the bird, wasn’t surprised. He explained that movements made during flight, eating and crowing are mainly controlled by nerve centers that aren’t located in the brain.

“The skulls of pigeons are sometimes opened for experiment, the brains taken out, the cavity fills with absorbent cotton, and the wound closed. After this the birds fly about all right. The most wonderful part of this rooster, however, is that the shock of the amputation did not kill him,” McElroy said.

When the article was written the rooster had been alive for two months. It didn’t travel the country like Mike, but it did have its own series of adventures. A chicken thief allegedly snuck into the stable one night and stole the rooster—not realizing it was missing its head.

“In the light of the match that he lit he saw a headless rooster poking his neck around in a vain effort to find out what the intruder wanted,” the paper reported. “The chicken thief fled with a yell.”

He probably ran around like a chicken with its head cut off.

![Toby The Sapient Pig, 1817 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.weirdhistorian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Tobythesapientpig-1871-crop-235x190.jpg)