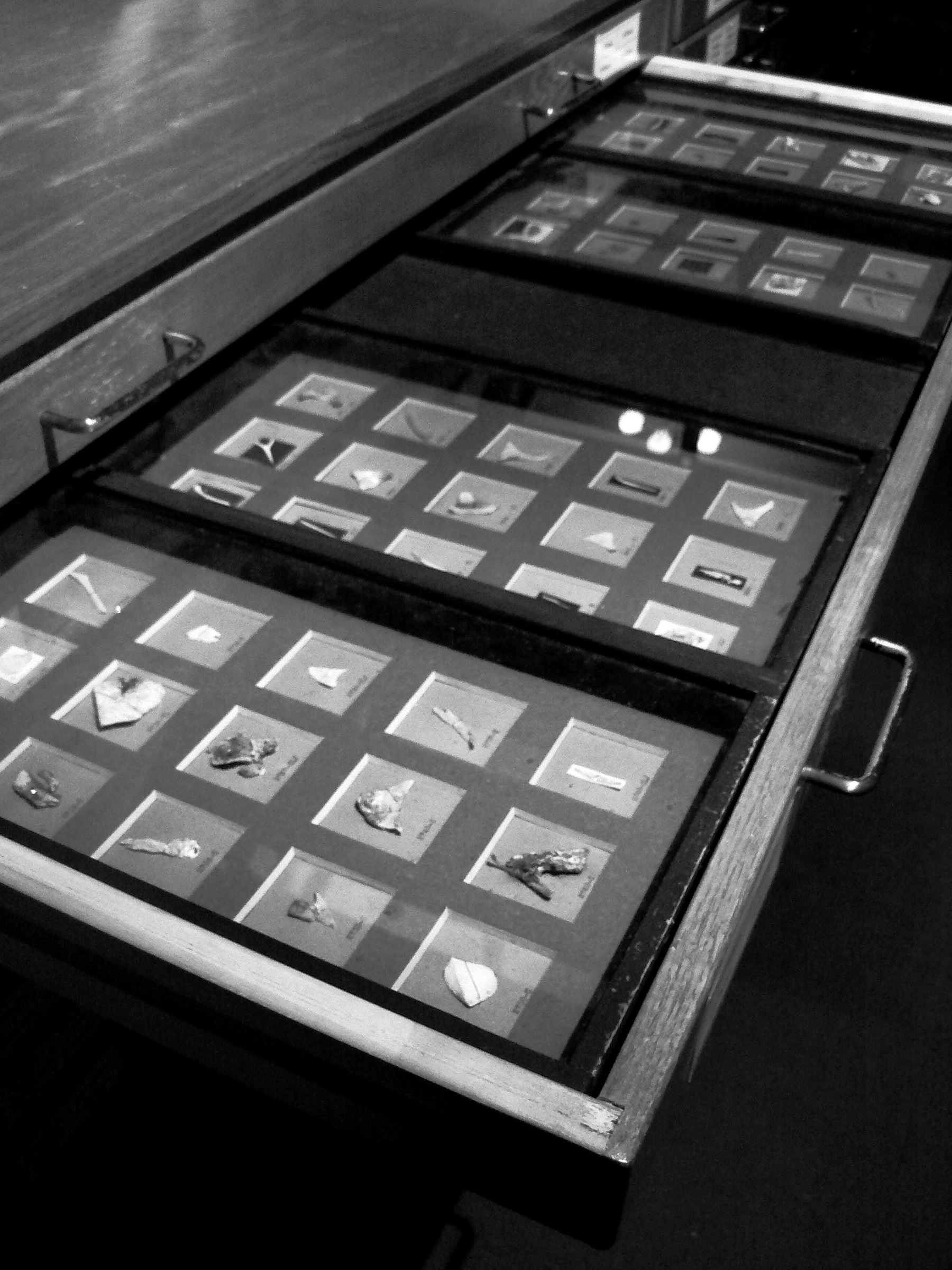

In a museum filled with preserved abnormal fetuses, skeletons of giants, and an 8-foot colon, what makes a cabinet full of safety pins, small trinkets and other random items one of the most fascinating exhibits?

These objects, on display at the Mütter Museum of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, seem unremarkable until you discover each was swallowed, extracted and carefully catalogued. And there are thousands of them.

The collection was assembled and donated to the museum by Chevalier Jackson, a pioneering laryngologist of the late 19th and early 20th century.

From the collection of the Mutter Museum, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia

Jackson developed innovative techniques and instruments to safely extract foreign bodies from the esophagus and airways, essentially creating modern endoscopy. He performed this service in Philadelphia, saving thousands of lives, and kept each of the objects removed. While the Mütter Museum displays a great portion of the items, the actual case studies of the patients are kept at the National Library of Medicine in Maryland.

As visitors to the museum explore the various drawers they’re left with a sense of astonishment and wonder. How could someone swallow such things? And how did someone get them out?

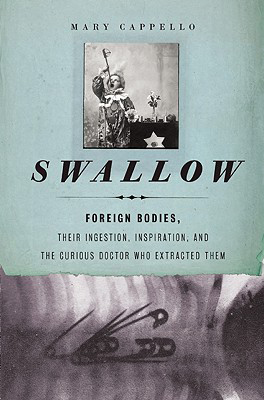

These questions, and more, are answered in Mary Cappello’s book, Swallow: Foreign Bodies, Their Ingestion, Inspiration, and the Curious Doctor Who Extracted Them (The New Press).

In it, we learn much more about not only Jackson, but the lives of the people who once ingested the objects on display.

Cappello, a professor of English and creative writing at the University of Rhode Island and a 2011 Guggenheim Fellow, first stumbled upon the exhibit during a trip to see the giant colon display. “What on earth is this?” she remembered thinking.

Swallow, by Mary Cappello (The New Press)

“Opening the drawers is one thing, dwelling with them is another,” Cappello says. “You rediscover the lives of the people attached to the case histories. It runs the gamut from comic to tragic. In some cases, it’s not about accidents, it’s about voluntary swallowing, a social history of hunger, confounding human psychology, class, race.”

Take, for example, the 1923 case of a baby boy, Joseph B. According to Jackson’s account, he removed 32 foreign bodies from within the child: buttons, safety pins (closed), bent straight pins, cigarette butts, burnt matches and more.

The mother had been ignoring signs at home, dismissing such evidence as a button in Joseph’s stool by thinking it must’ve fallen off his clothing. Buried inside the case study, Cappello found what she considers a “throwaway line” offering an explanation: “According to a statement made by both the father and the mother the child was cared for by a friend on May 28, and they believe that she deliberately fed these many articles to the child.” The question of why this caretaker would have done such a thing is not discussed.

“Jackson wasn’t really interested in human psychology,” Cappello says. “He was trying to master the foreign body. But he had to leave certain things out of his inquiry. He mastered it as a mechanical problem. But not the problems the foreign body presented to him when it involved human psychology.”

While many cases may have involved bizarre psychological circumstances—either forced by another or self inflicted—Jackson preached carelessness as the main cause of foreign body ingestion. In a 1937 article, he wrote: “Chew your milk!” He continued to explain that people eat too fast, and that even milk should be sipped and rolled around in the mouth, mixed with saliva before swallowing.

From the collection of the Mutter Museum, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia

As for things that should never be chewed—let alone put in the mouth—Jackson found blame in the swallower or someone indirectly related. A sharp-pointed piece of wire in a woman’s esophagus “points to the carelessness of using an old broken egg-beater in making the custard pie.”

Among his other theories: “Care should be taken, when cooking or serving food, to see that there are no loose pins or buttons in the waist that could fall into the food.” And, “Chewing of pencils, toothpicks, grass, stalks, straw, etc., apart from general objections, is a source of foreign body accidents.”

But Cappello digs deeper.

“Jackson never considered that poor children might have swallowed objects more frequently not because they were the victims of careless caretakers or lacked self-control but because they were starving,” she writes.

The Mütter Museum’s exhibit of the collection opens on two sides to allow greater access for visitors. A variety of Jackson’s endoscopy instruments and his illustrated artwork of the techniques he used in extractions joins the many drawers of swallowed objects.

“It’s an art object as much as it is a testament to the stories of patients and a testament to the work of this doctor,” Cappello says of the exhibit. “A beautiful and intriguing, strange work of art.”

Since the book’s release in 2011, Cappello has uncovered a manikin built by one of Jackson’s assistants, Angelique Piquenais. “The doll was used in a variety of ways,” Cappello explains, “not least to help quell children’s fears by showing what would be done to them with the endoscope (though, one look at the doll makes one wonder how it could really work to quell fears! It is rather scary looking).”

The doll has been donated to the museum and is now part of the exhibit.