With a few knocks on walls and raps on tables back in 1848, Kate and Maggie Fox began the nationwide craze of talking to the dead. The apparent mediumistic powers of the Hydesville, New York, sisters—not older than 14—kicked off the Spiritualism movement and a whole new wave of wonder about what lies beyond the veil.

Among the earliest to capitalize off the Fox sisters’ phenomenon were two brothers, Ira and William Davenport. The boys’ séances would soon develop into an extraordinary exhibition unlike anything anyone had seen before.

Ira and William were born in Buffalo, just a few hours away from Hydesville, in 1839 and 1841, respectively. As children they learned the art of rope-tie escapes from their father, a detective who had witnessed others perform such feats—clearly with a keener eye than most. This skill allowed them to create a séance in which the boys could be tied up in their chairs before connecting with spirits. Their ghosts typically manifested themselves by playing a selection of instruments left in the center of the room, often guitars and banjos. This, of course, happened in an entirely dark space.

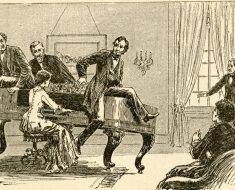

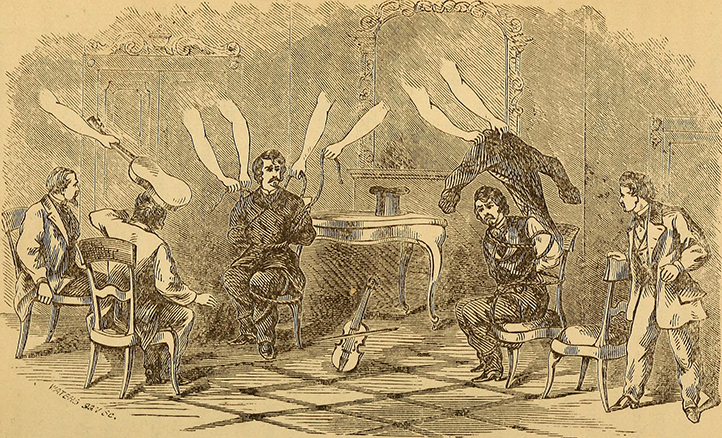

After some local séance circles in the early 1850s, the Davenports thought they were ready for the big time, so they made their way to New York City. Eager Spiritualists were seated against the wall, leaving the open space for the spirits to roam free and play a few tunes while the boys remained tied up at a table in the center of the room.

As P.T. Barnum wrote in his 1865 book, Humbugs of the World, “the noise made by ‘the spirits’ was about equal to the united honking of a large flock of wild geese.” Sometimes, he noted, a guest would “get a ‘striking demonstration’ over his head!”

The boys, whose perfect innocence was assumed, were going along just fine until a policeman attending a séance decided to spoil all the fun by lighting a lantern in the middle of a show. Ira and William were seen running around with the instruments in their hands. That put a damper on things, and the audience left in anger. The Davenports tried to salvage their stay in New York City with private séances, but further flubs didn’t help. Neither did claims that spirits were responsible for any deceptive acts.

So the boys and their father retreated to their home near Buffalo, where, as Barnum put it, “they continued to hold ‘circles,’ hoping to retrieve their lost reputation as good mediums—by being, not more honest, but more cautious.”

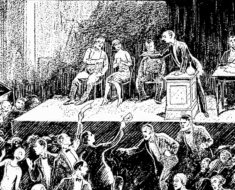

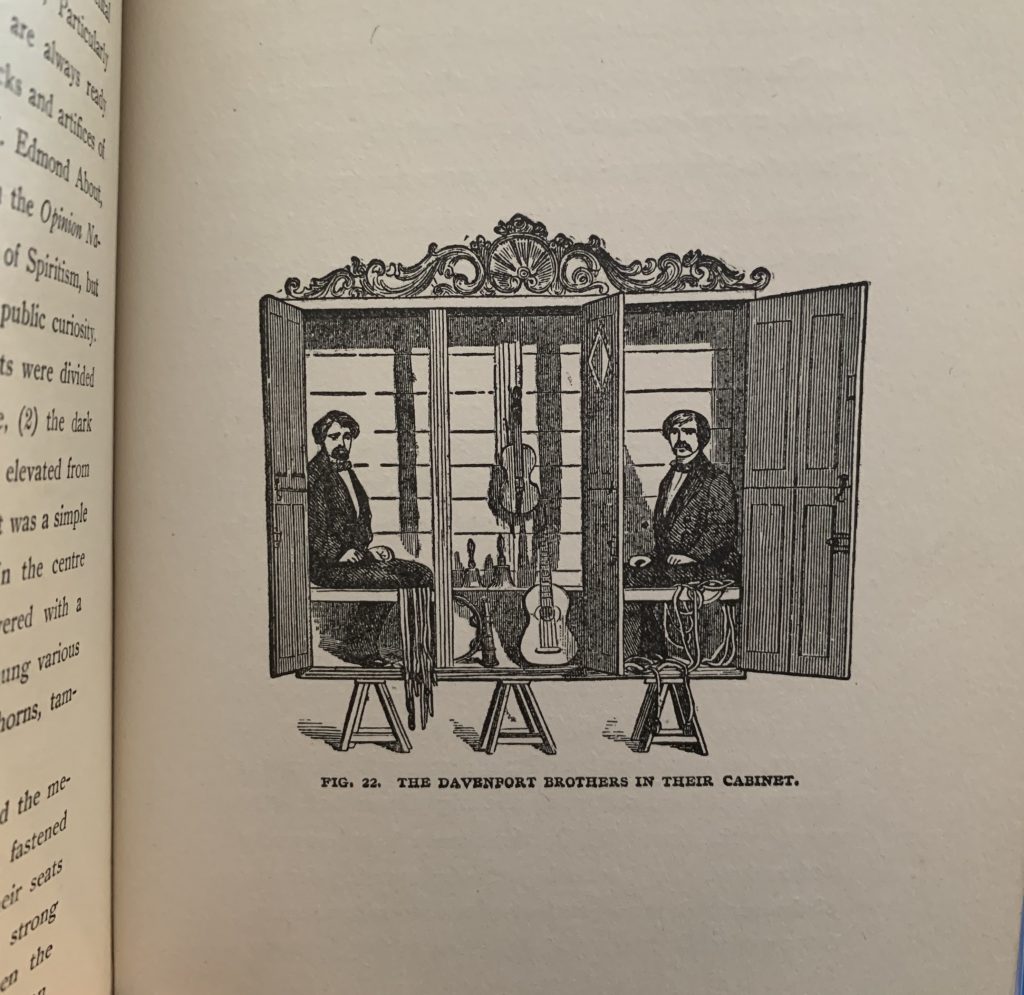

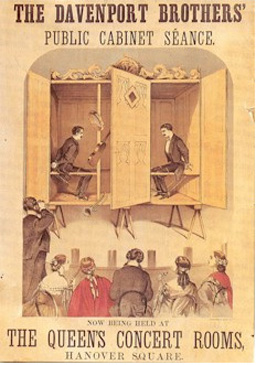

Being more cautious led to the development of the spirit cabinet, allowing for a controlled environment where skeptical audience members couldn’t so easily disrupt the experience. This Davenport cabinet was about six feet wide, six feet high, and two-and-a-half feet deep. It was split into three sections with three doors: the left and right segments had a bench for each brother to sit on, facing each other; the middle section held an array of instruments, and its door had a small window at the top with a black curtain. The entire cabinet was elevated from the floor by three sawhorses.

Shows began with volunteers being called on stage to tie the Davenports at the wrists, feet, and to their benches. Their feet were also bound to each other. As far as anyone could tell, the young men were securely trapped inside. The doors closed and, after a brief period, were opened to reveal that the brothers had been completely freed of the ropes. The doors were shut once more, and after a couple of minutes opened again. This time, Ira and William were fully bound once more. The spirits, it seemed, were quite adept at rope ties and escapes.

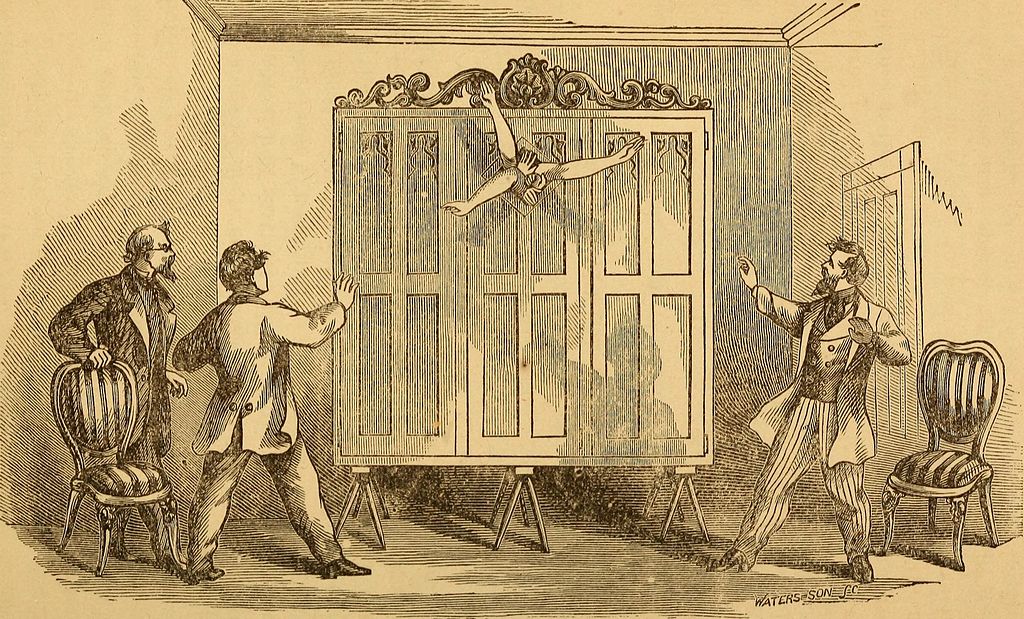

But the real show began once the doors closed again. This time, as Henry Ridgely Evans described it in his 1897 book, The Spirit World Unmasked, “Pandemonium reigned. Bells were rung, horns blown, tambourines thumped, violins played, and guitars vigorously twanged. Heavy rappings also were heard on the ceiling, sides and floor of the cabinet, then after a brief but absolute silence, a bare hand and arm emerged from the lozenge window, and rung the big dinner bell.”

Adding to the spectacle, the Davenports would invite an audience member into the cabinet. After the ruckus inside, this volunteer would emerge with his hat pulled over his eyes and his coat turned inside-out. At times the brothers would even hold a fistful of flour in their hands. After the “spirits” finished their concert, Ira and William would be seen still holding the flour, secure in their ropes.

Audiences were mystified and the press loved it. This quote from the March 19, 1869, New York Daily Tribune adds to Evans’ description: “… twice a bare arm was thrust forth, almost as mysterious as that which rose out of the lake (in the legend) and took King Arthur’s sword. This arm and these hands may have belonged to the Davenport Brothers; but if they did, the Davenport Brothers are the cleverest jugglers of this age, or of any age in which juggling has been known.”

After the cabinet portion of the show, the Davenports held a dark séance, in which they were once again tied up, and the instruments ran amuck for another gig. This second act wasn’t far from their original New York City performance, but they were now more skilled, and even added phosphorescent oil to the instruments, so they glowed as they appeared to float around the stage.

Throughout the shows, Ira and William remained quiet, simply performing their feats and letting people think what they wished. Were they magicians or mediums? Lecturers introducing them often spoke of Spiritualism, but it was up to the audience to decide. Many believed, but they had their share of naysayers who claimed they were frauds. It didn’t hurt business though. Fortunately for them, there was no social media or TV, so they were a fresh act from town to town.

All was good and well until the Civil War hit and started to impact business. To keep the profits flowing, the Davenports brought their talents abroad to Europe. There, the media and audiences began challenging their authenticity. One such example came after playwright Dion Boucicault, who had plenty of experience with theater trickery, hosted the brothers for a group of friends and, after a two-hour performance, detected no deception. The press thought he’d be fooled. In Hiding the Elephant, Jim Steinmeyer shares Boucicault’s defense:

“Some persons think that the requirement of darkness seems to [imply] trickery. Is not a dark chamber essential in the process of photography? And what would we reply to him who would say, ‘I believe photography to be humbug—do it in the light, and we will believe otherwise?’”

They survived the media skepticism, but then they ran into bigger troubles. Some audience members decided to tie knots with a bit more skill than the average volunteer had. The Davenports would complain about the tightness and even show blood. The ropes would be cut and the show ended. But the biggest hit they took happened in 1865 when a young magician named John Nevil Maskelyne happened to catch a peek through the window at a moment when the drapery fell. Ira could be seen loosened from his ropes and manipulating the instruments.

“There sat Ira with one hand behind him and the other in the act of throwing,” Maskelyne later recounted. “In an instant both hands were behind him. He gave a smart wriggle of his shoulders, and when his hands were examined he was found to be thoroughly secured—the ropes, in fact, were cutting into his wrists.”

Maskelyne, along with a partner and cabinet builder, George Cooke, soon replicated the apparatus, learned the Davenports’ technique and began doing their own show. Other imitators would soon follow.

The Davenports mastery of escape was helped by the knowledge that volunteers wouldn’t be experts at tying knots, especially if they selected high-profile businessmen or celebrities in attendance—the kind of people who aren’t typically skilled in the art of rope tying. If they felt too much pressure, a simple grunt or tensing of the muscles would signal the volunteer, who’d naturally ease up.

Audience members who joined them in the cabinet were simply plants. And as for the flour in the hand, well, they deposited it in their pockets, then grabbed another handful before revealing themselves at the end.

Still, despite being exposed and imitated, business continued, even after William’s death in 1877. Ira carried the act on with longtime promoter, William Fay, into the 1890s.

The Davenports’ secrets were revealed to Harry Houdini just before Ira’s death in 1911. Houdini had paid him a visit out of respect and curiosity. Ira’s final message to Houdini, as Steinmeyer reports, was, “Houdini, we started it, you finish it.”

If Ira felt responsible for popularizing Spiritualism and wanted to put an end to such beliefs, Houdini was the man for the job. The famed magician would later expose mediums whenever and however possible.

But even Houdini couldn’t make people stop believing. After Ira admitted it was all an act, people still thought otherwise. An obituary for the elder brother noted that “many Spiritualists continued to believe that the Davenports were assisted by unseen agency.”

This power of belief, of course, was the foundation upon which the entire movement was built.