In the early 1900s there was much excitement about the possibility of life on Mars. After all, several astronomers had claimed to observe canals on the Red Planet. Someone had to have made them. And at the turn of the century, Nikola Tesla believed he received wireless signals straight from Mars. Martians, he thought, were trying to contact us. But it wasn’t just scientists promoting the idea of extraterrestrial life. There was also Edmond Perrier, Director of the French Botanical Society.

Edmond Perrier described Martians with great specificity. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Perrier had no doubt that plants and flowers grew on Mars and was certain the planet was inhabited. In a 1912 interview with the New York Times, he explained that due to the “lightness of the atmosphere on Mars and the comparative absence of fierce light, vegetation is luxuriant and the Martians are probably people like the giant Scandinavians.”

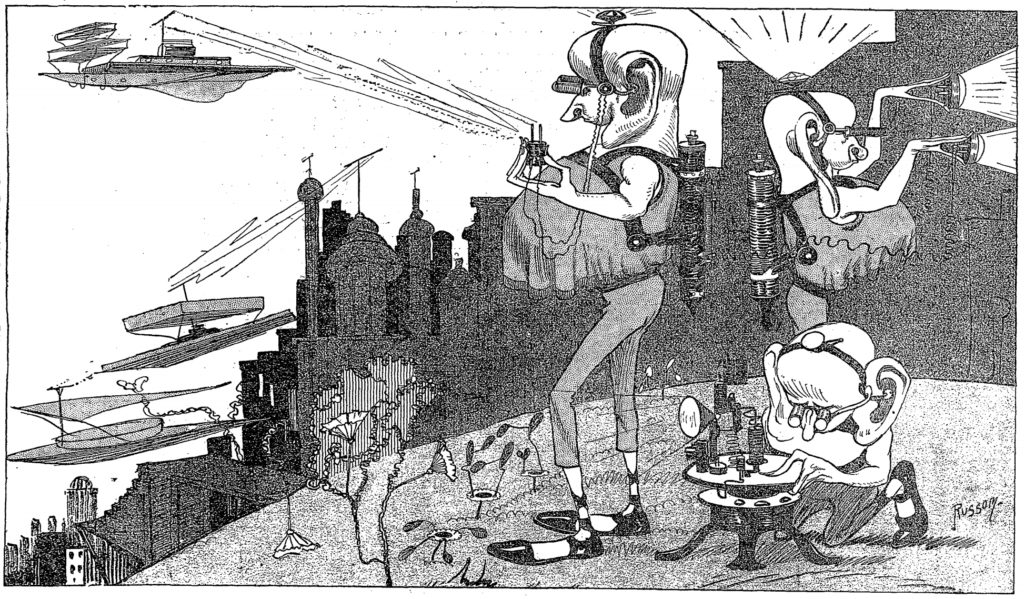

The article further explained that Perrier believed the Martians were “about twice the size of human beings, and have enormous noses and large protruding eyes. Their eyes are probably blue and their hair is almost white. They have no necks, no waists, very prominent ears, and large heads and bodies, supported by very thin legs and very small feet.”

Their height and slender legs were attributed to the light force of gravity (the latter, because it took little effort to walk) and the blond hair due to the less intense daylight. In addition, the thin atmosphere would result in the Martian’s lungs and chest being quite large.

By 1920, Perrier’s beliefs, if anything, grew stronger. In a New York Tribune article he described life as “grand, intense, formidable,” since the seasons were much more extreme and the years longer. Animals and insects, he claimed, were similar to those on Earth, but much larger.

”The year on Mars is twice as long as our earthly one,” Perrier explained, “and hence plants and insects have twice the time in which to evolve. Mars is the land of huge plants and ideal flowers, of birds abnormally powerful in song and wondrous in appearance, and of four-footed animals with extraordinarily developed fur and skin.”

Beyond the physical characteristics of Martians that he described in 1912, he also believed they had superior intelligence.

“Touching on the question of intelligence, the French savant deduced that the Martians have solved the problem of existence, and know no such thing as industrial strife,” the paper reported. “Being older, they are also wiser than we. They have long since conquered disease, and know the hour of their demise, awaiting the event calmly. They have overcome poverty, are too sophisticated to engage in war, and need no law or government to keep them orderly. Philosophers and brothers, they live in amity and understanding, devoting all their thought to the promotion of large undertakings in which selfishness, avarice and earthly trifles have no part.”

This description, Perrier noted, was far different than the way H.G. Wells portrayed them in his novel, War of the Worlds. Wells’s Martians had roundish bodies and long tentacles. And of course, they were evil.

Perrier feared Wells’s version of our planetary neighbors did them a “great injustice and created a prejudice against them, which is not only unscientific and unsound, but entirely undeserved.”

Once communications were established with Martians, Perrier wanted to ensure we Earthlings would be welcoming, not fearful.

While others agreed that the Red Planet was inhabited, they didn’t necessarily share Perrier’s detailed descriptions. French astronomer, Camille Flammarion, told the New York Times after the 1912 interview that he didn’t agree with the botanist’s specificity, but felt that his assumption of “luxuriant vegetation” was likely correct.

The canals, which caused so much of the excitement, were later proven to be an optical illusion.

Edmond Perrier’s Martians illustrated in the New York Times Magazine, 1912.

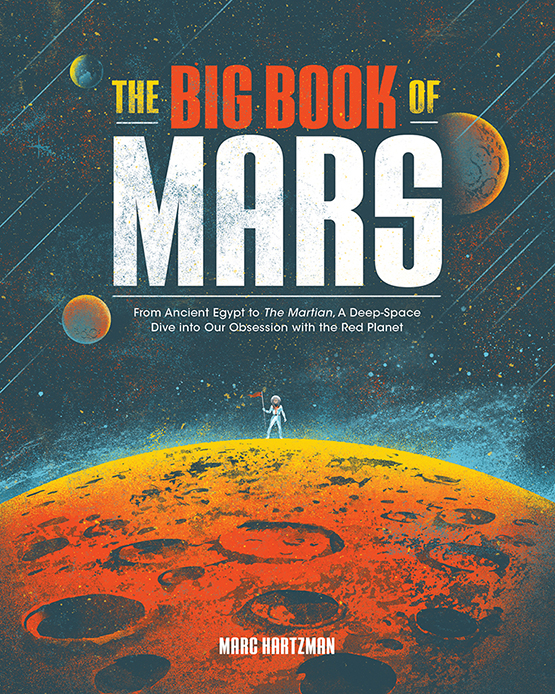

Read more about Edmond Perrier and other ideas about Martians in The Big Book of Mars, written by Marc Hartzman. Available at bookshop.org, Amazon, at Barnes & Noble, or wherever you buy books.

![Premature Burial [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons-Illustration for Edgar Allan Poe's story The Premature Burial by Harry Clarke (1889-1931), published in 1919.](https://www.weirdhistorian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/premature-burial-crop-235x190.jpg)