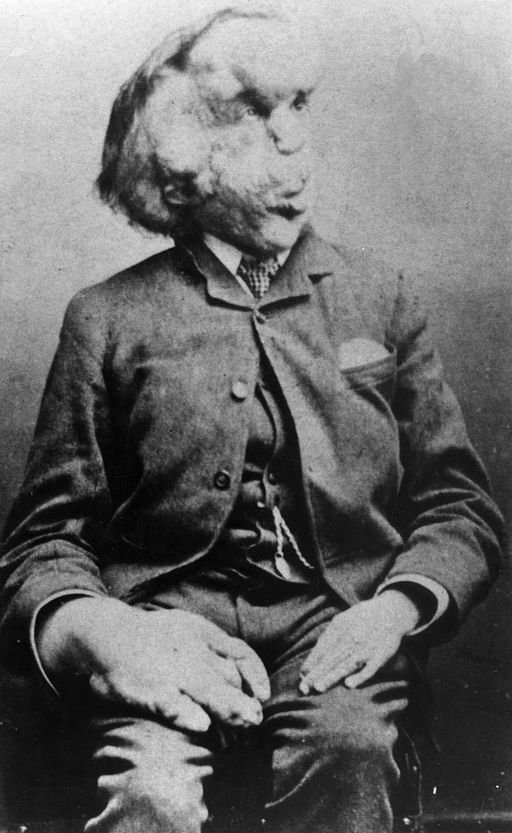

Joseph Merrick, the Elephant Man

There stood revealed the most disgusting specimen of humanity that I have ever seen. In the course of my profession I had come across lamentable deformities of the face due to injury or disease, as well as mutilations and contortions of the body depending upon like causes; but at no time had I met with such a degraded or perverted version of a human being as this lone figure displayed.

So said Sir Frederick Treves of the Royal London Hospital regarding the first time he laid eyes on the Elephant Man, Joseph Merrick.

Merrick was born in Leicester, England on August 5, 1862. His deformity began developing by the age of 21 months and grew worse with time. Regardless, Merrick went to school until the age of 12 and began working in a cigar factory by 13. Sadly, his condition made him more and more clumsy, until he eventually could no longer handle the job. Ultimately, he ended up being exhibited as a freak in London.

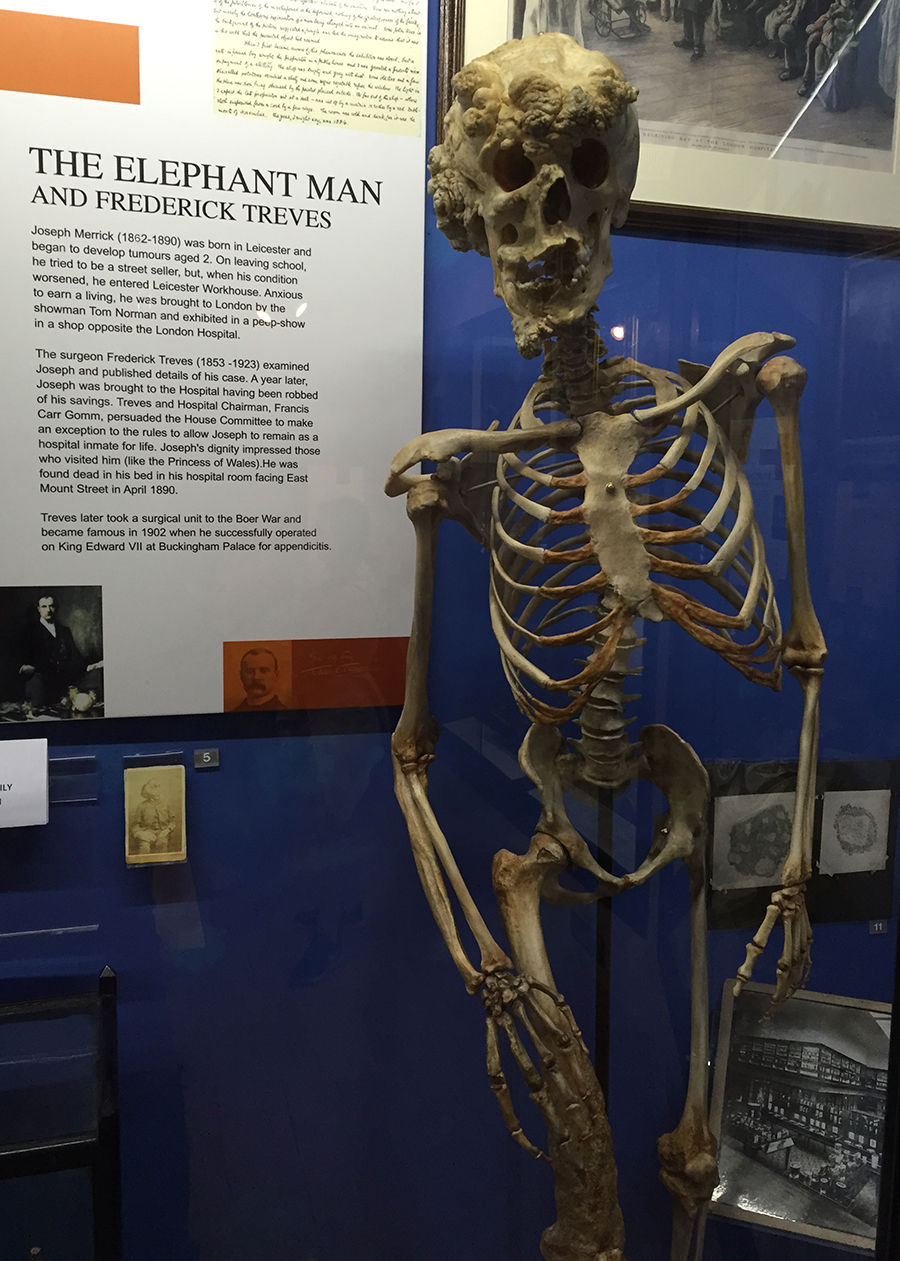

By this time his head had bulging bony masses and cauliflower-like chunks of skin protruding from all parts of his body. His right arm grew enormous and was shaped somewhat like a paddle, rendering it nearly useless. Contrarily, his left arm was virtually unaffected. Merrick’s condition was first diagnosed as elephantiasis. In 1976, a doctor determined it was more likely a severe case of neurofibromatosis. The diagnosis was altered once again in 1996 as an extremely rare condition called Proteus syndrome.

The Elephant Man’s sideshow career was ended by Treves, who convinced Merrick’s showman, Tom Norman, to allow him an examination at the hospital. Although Norman continued to tour with Merrick afterward, the exhibition was short-lived. People were too appalled by his appearance and profits waned. The show closed and the Elephant Man found his way back to Treves. By 1886, after some internal negotiations, the doctor was able to secure a permanent room for the Merrick to call home.

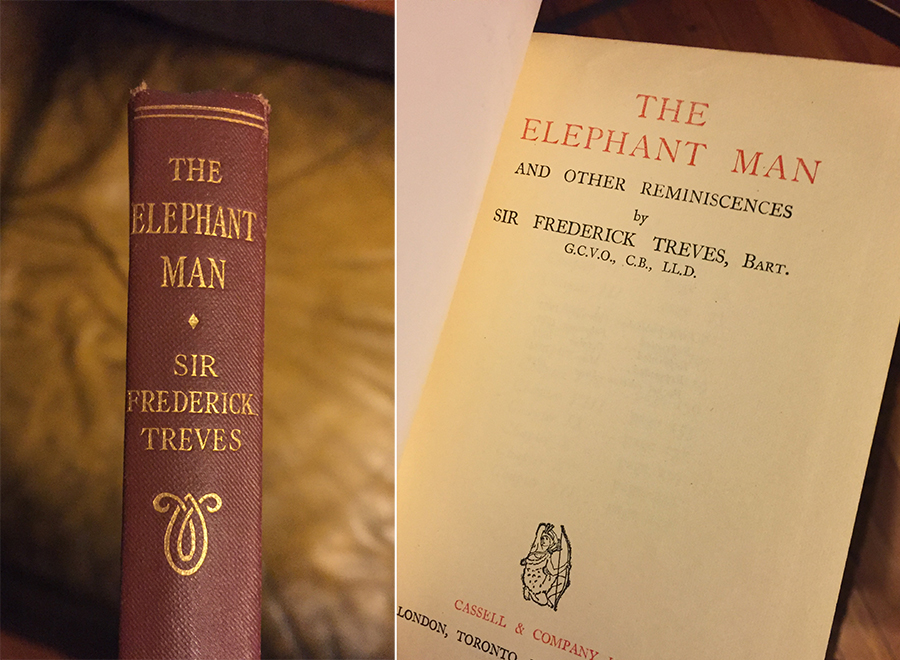

“Merrick had now something he had never dreamed of, never supposed to be possible—a home of his own for life,” Treves wrote in The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences.

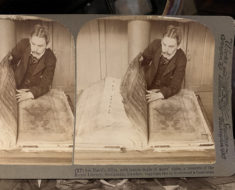

The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences, by Sir Frederick Treves, 1923. Photo by Marc Hartzman.

Despite his physical deformities, Merrick’s mind, much to Treves’ surprise, was unaffected. “I supposed that Merrick was imbecile and had been imbecile since birth,” he wrote. “The fact that his face was incapable of expression, that his speech was a mere spluttering and his attitude that of one whose mind was void of all emotions and concerns gave grounds for this belief.”

But as Treves spent time with Merrick and got to know him, his opinion changed. He found the Elephant Man to be “remarkably intelligent” and curious. “He had learnt to read and had become a most voracious reader,” Treves wrote. “I think he had been taught when he was in hospital with his diseased hip. His range of books was limited. The Bible and Prayer Book he knew intimately, but he had subsisted for the most part upon newspapers, or rather upon such fragments of old journals as he had chanced to pick up.”

The gentle and thoughtful Merrick soon became a local celebrity, often visited by many of London’s elite. In a sense, he was still on exhibition with Treves acting as a more civilized showman.

On April 11, 1890, Merrick passed away in his attempt to act like normal people. Because of his oversized head, he was forced to sleep sitting up to avoid asphyxiation. His desire to lie flat cost him his life.

Years after the passing of his friend, Treves wrote:

As a specimen of humanity, Merrick was ignoble and repulsive; but the spirit of Merrick, if it could be seen in the form of the living, would assume the figure of an upstanding and heroic man, smooth browed and clean of limb, and with eyes that flashed undaunted courage.

His tortured journey had come to an end. All the way he, like another, had borne on his back a burden almost too grievous to bear. He had been plunged into the Slough of Despond, but with manly steps had gained the further shore. He had been made a ‘spectacle to all men’ in the heartless streets of Vanity Fair. He had been ill-treated and reviled and bespattered with the mud of Disdain. He had escaped the clutches of the Giant Despair, and at last had reached the ‘Place of Deliverance,’ where his burden loosed from off his shoulders and fell from off his back, so that he saw it no more.

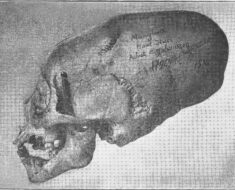

Replica of the Elephant Man’s bones at the Royal London Hospital. Photo by Marc Hartzman.

Today, a replica of the Elephant Man’s skeleton can be seen at the Royal London Hospital. For more of Treves’ reminiscences, read the full chapter here.

As for my own reminiscences, I first met the Elephant Man when I was 7 years old. The encounter was on the screen, watching David Lynch’s 1980 film, The Elephant Man. I was immediately fascinated, and have remained so ever since. How could the human body go so wrong? I wondered. Yet, inside Merrick stirred a gentle spirit who just wanted to live as a man. As he shouts at a crowd in the film, “I am not an animal! I am a human being!” How fortunate for him that his path crossed with Treves’ and he was finally treated like one.