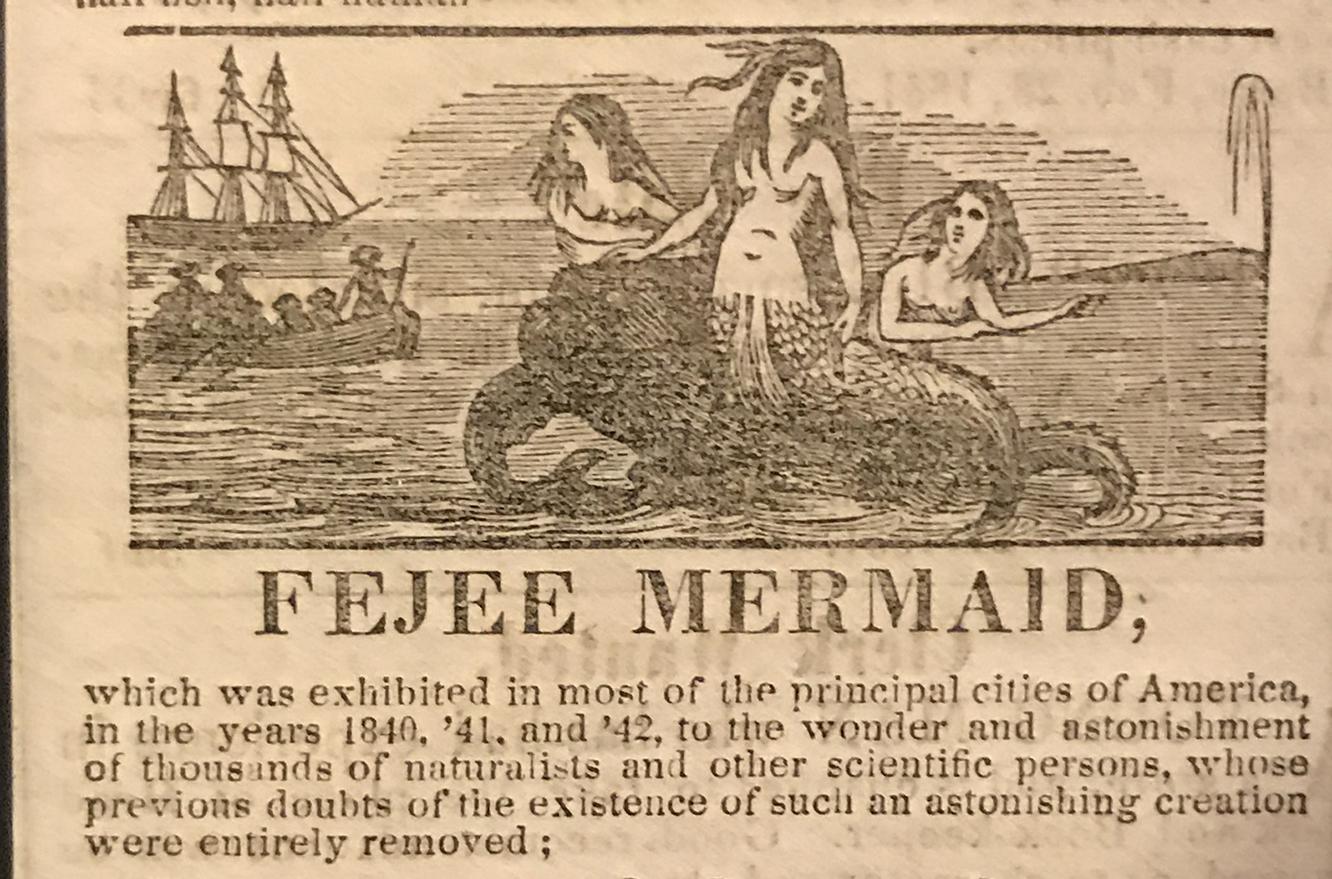

![The Feejee Mermaid was exhibited in 1842. By P. T. Barnum (P. T. Barnum) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.weirdhistorian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/By-P.-T.-Barnums-P.-T.-Barnums-Public-domain-via-Wikimedia-Commons.jpg)

The Feejee Mermaid was exhibited in 1842. By P. T. Barnum (P. T. Barnum) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

P.T. Barnum capitalized on this credulity with his famous Feejee mermaid in the mid-1800s. The beast was created with a monkey head and torso attached to a fish’s body.

Today, we all look at Barnum’s mermaid as an amusing gaff. But at the time, there were those who were convinced it was real. Even as late as 1932, The Victoria Advocate reported that a cotton merchant from Gainesville, Texas was defending the showman’s monkey-fish as being genuine.

According to the article, the man “remembered he had seen such a creature in the waters along the coast of Jamaica in 1894.” He claimed a fisherman caught the mermaid, matching the description of Barnum’s. Frightened, he threw it back in the water. The man said he saw its head and arms, “similar to that of a human being, at close range.”

Long before this fellow, many other witnesses described similar encounters, and with similar certainty.

In 1493, Christopher Columbus claimed to have spotted three mermaids while sailing near the Dominican Republic. He described them as being “not half as beautiful as they are painted.” It was later discovered that Columbus’s “mermaids” were actually manatees.

Kirby’s Wonderful and Eccentric Museum (1820) includes a section titled “Curious Account of Mermaids” that begins with a confident statement regarding the mermaid’s existence:

“The most ingenious and impartial investigators of natural history, have now rescued the truth from a mixture of error.”

The author continues to describe mermaids as “sea apes” that taste like pork and “shriek and cry like women” when they are caught.

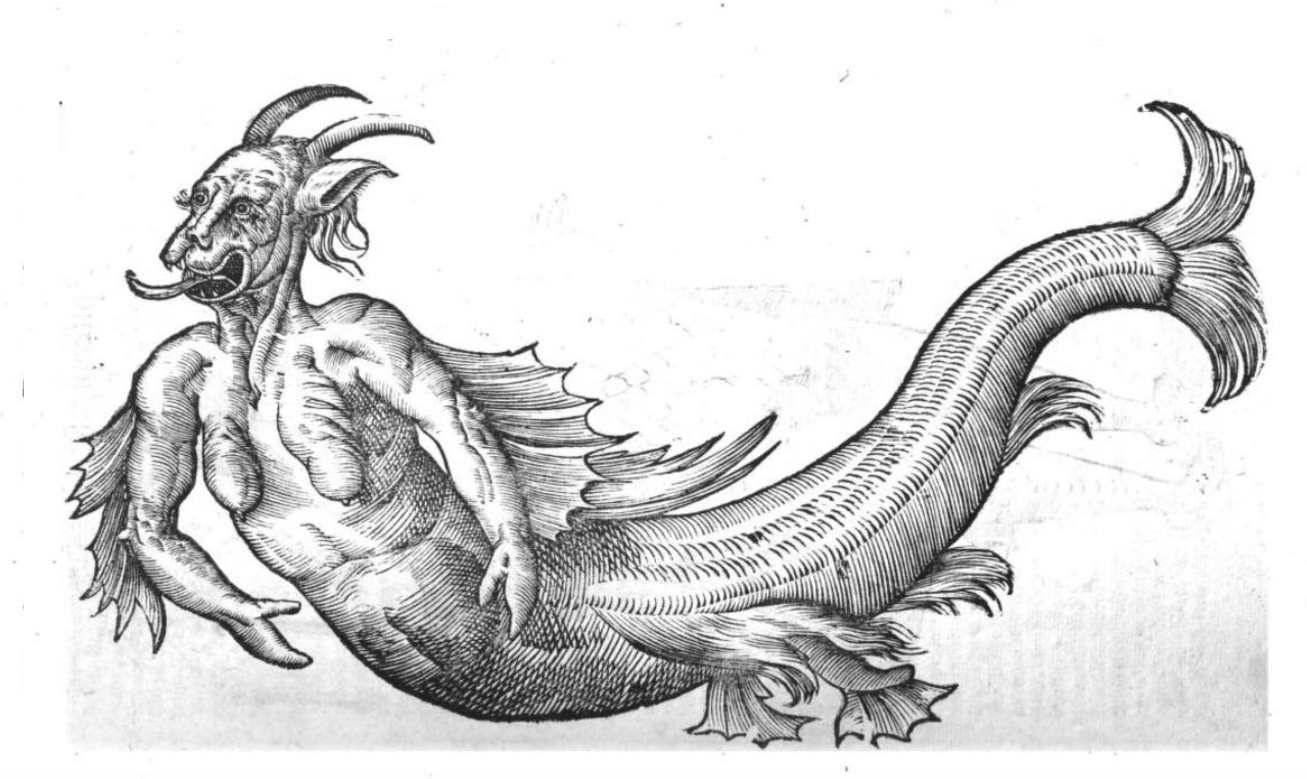

A mermaid seems to recoil from the advances of a merman. Illustration from Monstrorum Historia (1642) by Vlyssis Aldrouandi.

A similar creature, the book alleges, measures approximately six feet in length, has a face like a man and is found in the seas and rivers in the southern parts of Africa and India, and in the Philippines, Molucca islands, Brazil, North America, and Europe. The book adds further details:

It has a high forehead, little eyes, a flat nose, and large mouth, but has no chin or ears. It has two arms, which are short, but without joints or elbows, with hands (which are not very flexible), connected to each other by a membrane, like that of the foot of a goose. Their sex is distinguished by the parts of generation. The females have breasts to suckle their offspring; so that the upper part of their body resembles that of the human species, and the lower part that of a fish. Their skin is of a brownish grey colour, and their intestines are like those of a hog. Their flesh is as fat as pork, particularly the upper part of their bodies; and this is a favorite dish with the Indians, broiled upon a gridiron.”

Several other accounts bring forth supporting evidence, including a case in 1670 describing a mermaid near the shore of the Faroe Islands, west of the Scandinavian peninsula. “She stood there two hours and a half, and was up to the navel in water; she had long hair on her head, which hung down to the surface of the water all round about her; she held a fish with its head downwards, in her right hand.”

Just decades earlier, in 1608, Henry Hudson reported that two of his sailors spotted a mermaid north of the Faroe Islands, during a voyage between Spitzbergen and Nova Zembla. The mermaid approached the side of his ship, and according to a 1935 Indianapolis News article, “Her face and breasts were those of a woman, but below she was a fish as big as a halibut and colored like a speckled mackerel.”

Not exactly Daryl Hannah. Illustration from Monstrorum Historia (1642) by Vlyssis Aldrouandi.

Similar to Columbus’s experience, the article suggests that the sailors likely saw a seal, which was not commonly known to Europeans at the time. The article adds one more account: “A few years later Capt. Richard Whitbourne reported seeing a mermaid in St. John’s harbor on the coast of Newfoundland. Whitbourne, like Hudson’s sailors, was no doubt the victim of careless observation. Walruses seen dimly at a distance often appear like mermaids.”

After all that time at sea, these sailors’ imaginations may have been perfectly happy to turn most anything into a siren of the sea. Or perhaps, they simply liked crafting marvelous or terrifying stories of the sea to share on land. In the days before zoological knowledge was widespread, who had any reason to disagree?