A visit to Amsterdam means many things to people. Rembrandt, Anne Frank, canals, the Red Light District, or maybe just getting high. For me, it meant a trip to Museum Vrolik—an extraordinary anatomy museum housed at the AMC Hospital, about 25 minutes outside of the city’s center. But that’s what Uber’s for.

My driver wasn’t aware of the museum, so he simply dropped me off at the hospital’s main entrance. I wandered inside, looking lost, and asked a woman at the information desk how to find the collection.

“It’s not in here,” she quickly responded. It’s not? Then she turned to another woman sitting in a motorized hospital cart, said something in Dutch, and circled back to me. “She’ll take you.”

Skull with cyclopia. Courtesy of Hans van den Bogaard/Museum Vrolik.

I hopped aboard and was carted away. It felt odd to be perfectly healthy and whisked around a hospital, but the front door service was greatly appreciated.

Inside the museum are a series of glass display cases presenting 2,000 anatomical specimens. I started at the fetal skeletons of conjoined twins that stand next to jars preserving their flesh counterparts. These included thoracopagus twins (joined at the thorax), similar to the original Siamese twins, Chang and Eng Bunker, but more severe.

Moving on, I discovered babies with different degrees of cyclopia lining shelves of another cabinet. Two jars held sufferers of Ichthyosis, better known as alligator-skin disease, while another nearby display featured a baby with phocomelia, a disease causing deformations of the arms and legs. I also stared curiously at a variety of specimens exhibiting conditions that afflicted arms, legs, eyes, hearts, the spine and genitalia.

It is not a place for the squeamish.

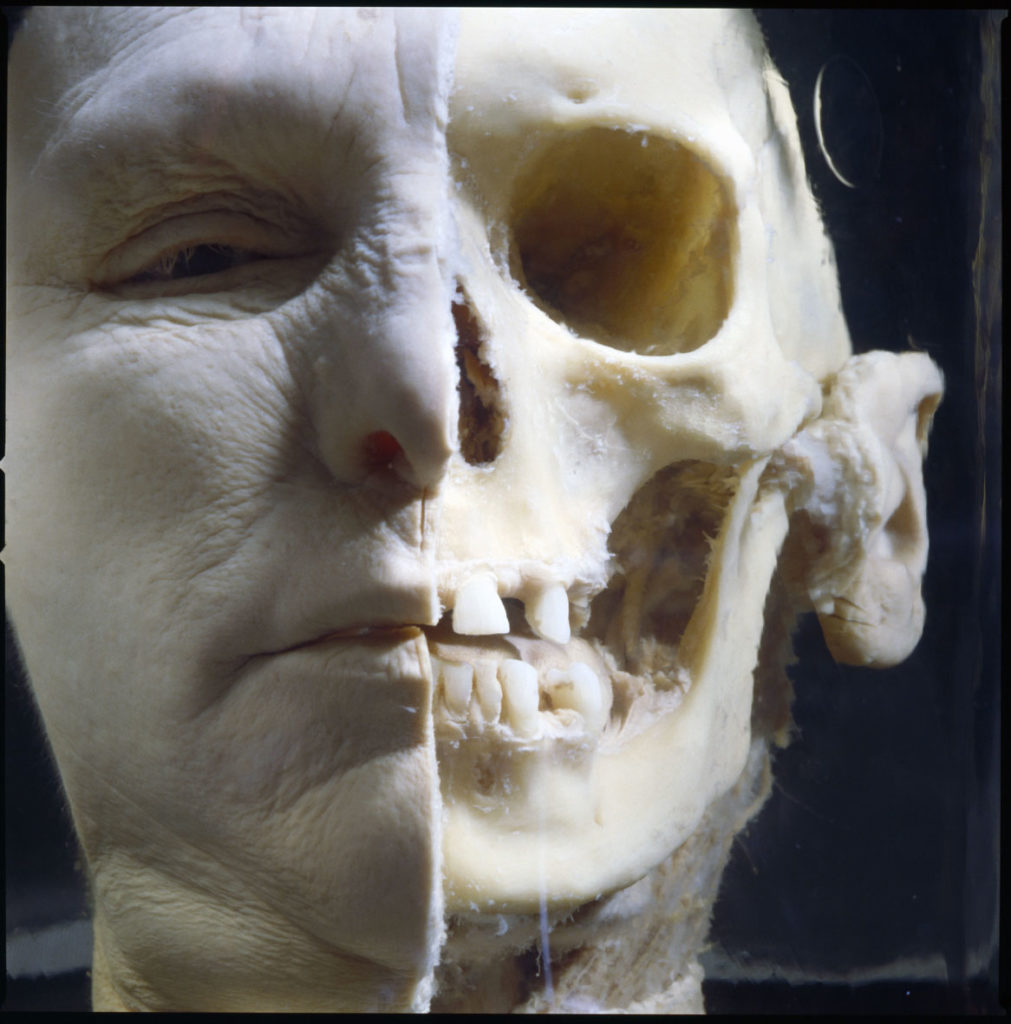

Half flesh, half skull. Courtesy of Hans van den Bogaard/Museum Vrolik

Set apart from the surrounding cabinets on its own pedestal sits a human head—half with flesh intact, half showing the skull within. The anatomist was attempting to show how thick the skin and tissue is from the exterior of our face to the bone. As the display demonstrates, it’s thicker than one might think.

Two thousand such specimens sounds like a lot, but it’s only a fraction of the collection, which amounts to 20,000 pieces. The other 18,000 are kept in three basement depots, heavily protected by thick walls of concrete built during the Cold War to withstand a nuclear blast. In addition to the human and animal specimens, the subterranean spaces are filled medical instruments, wax models, and books.

The collection began with Gerard Vrolik (1755-1859) and his son Willem (1801-1863). The two served as anatomy professors at the Athenaeum Illustre in Amsterdam, and clearly encountered many anomalies during their tenure. Willem took a special interest in teratology (the study of congenital abnormalities). He believed that humans were the highest order of form, and that natural forces allowed all living things to develop and grow into their specific form. Aberrations from the ideal human form meant there were either too many or too few formative forces. For example, conjoined twins meant an excess of forces, whereas a case of cyclopia indicated a lack of forces. It’s this concept that gave the museum’s book its title: Forces of Form.

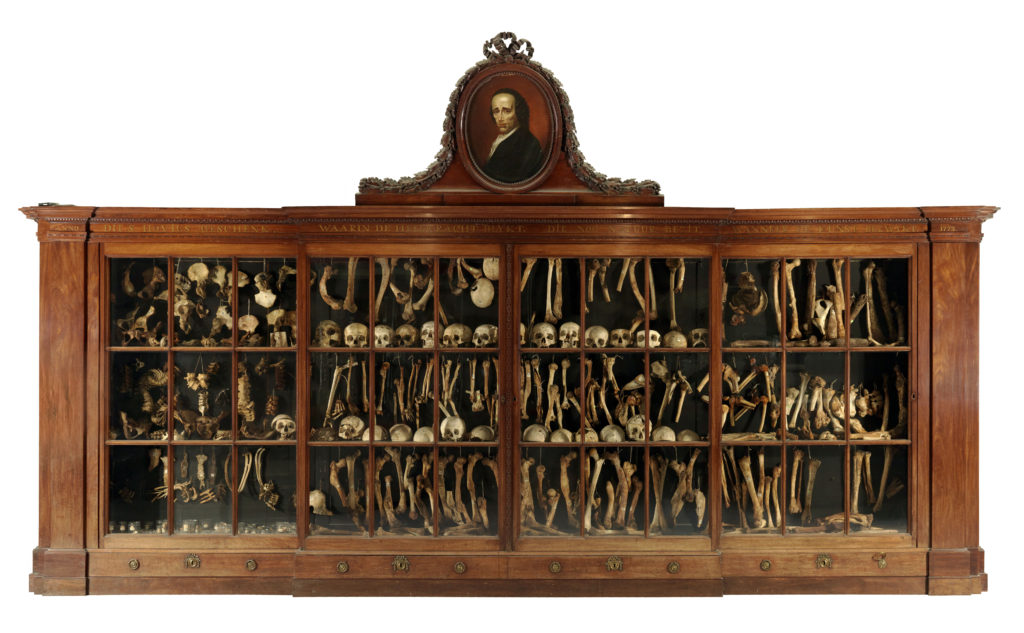

The Hovius Collection at Museum Vrolik. Courtesy of Hans van den Bogaard/Museum Vrolik

How did the Vroliks acquire such specimens? Did they just take stillborn children afflicted with various diseases straight from the hospital?

“There’s no documentation,” explains Sifra Wieldraaijer, PR Manager at the Museum Vrolik. “Our curator has tried to research that kind of stuff. There have been lots of books and articles written by the Vroliks, but they don’t say, so we don’t know for sure. We know in more recent times most people gave permission, but the Vrolik collection is from the 18th and 19th century, so we don’t know if the mothers gave permission or if it was done in secret.”

After Willem’s passing the private collection was moved to the Athenaeum Illustre, which, by 1877, would become the University of Amsterdam. Over the years other collections were added, keeping the museum growing until the early 20th century.

The Hovius Collection, for instance is housed in a large wooden cabinet at the back of the museum. It features numerous bones that physician Jacob Hovius excavated to research various ailments their owners suffered in life. Among the most interesting pieces is the skull of a man who was kicked in the face by a horse in 1750. The man’s cheekbone was broken and his face began to swell. Eventually his eye became blind and bulged from its socket. He lived this way for nineteen years. The skull shows how the socket grew and became malformed, even creating what appears to be a third socket.

Lambs with cyclopia. Courtesy of Hans van den Bogaard/Museum Vrolik

“It’s amazing to see how the body copes with such trauma and finds a solution,” Wieldraaijer told Weird Historian. “I wonder what he must’ve looked like, with an eye socket here that must have been empty. I don’t think it was a pretty sight.”

Aside from curiosity seekers, the museum is also frequented by doctors and medical students.

“It’s interesting for them to look at it in a really technical way, parts of anatomy – but I also really like that this is a historical collection,” Wieldraaijer says. “We have a liver where you can see that the woman wore a really tight corset, and the lion of the brother of Napoleon, so there’s another story to be told, not just from an anatomical sense.”

Not to mention the lotus foot, showing the deformation resulting from the once-popular Chinese foot-binding custom.

“So I hope they gain a bit of historical consciousness, or they are in wonder by that part of the collection, and look at this as a historical collection.”

The museum is open Monday through Friday, 11:00 am-5:00 pm. Before and after hours, of course, Amsterdam has plenty more to offer.