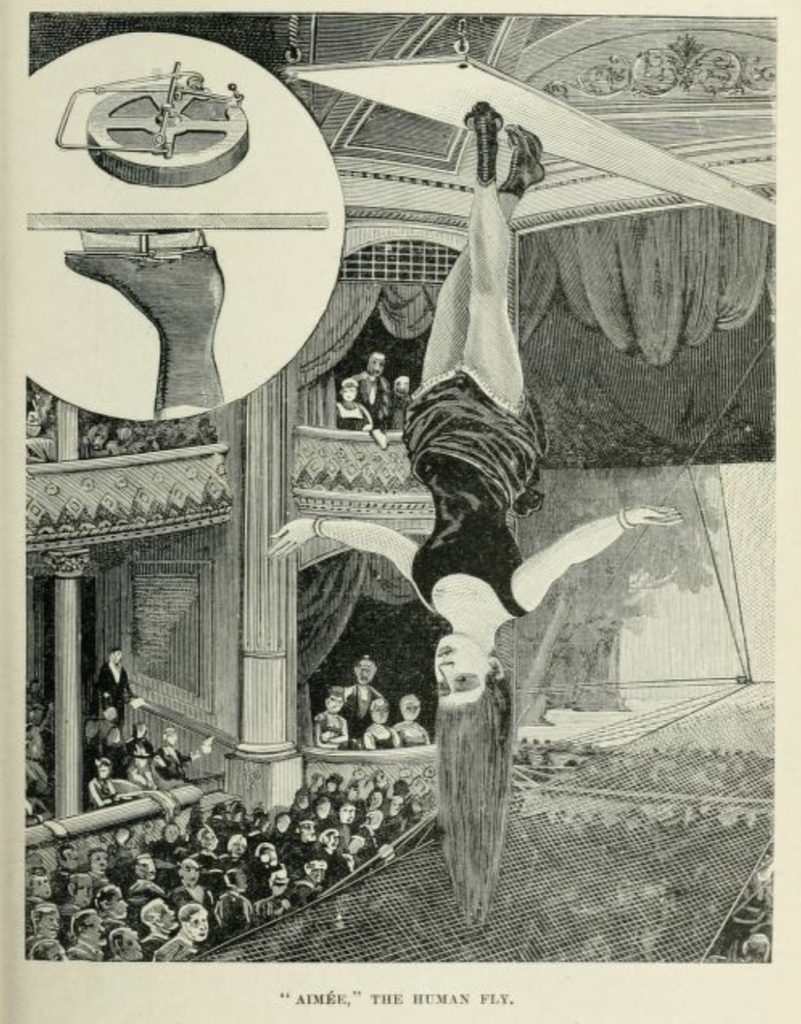

Aimée The Human Fly, one of the Victorian-Era ceiling walkers.

The circus arts have produced countless creative and innovative performers, from fire manipulators and animal trainers to human cannonballs and hair-hanging wonders. But among the most unique acts were the Victorian-era ceiling walkers. That’s right—people walking upside-down, on the ceiling. Like a gecko.

The performer featured here is from 1897’s Magic: Stage Illusions and Scientific Diversions. She was known as Aimée, The Human Fly. She’d begin her act by sitting on the trapeze and facing the audience, as any trapeze artist might do. Then, she’d roll back and raise her legs up until they reached a 24-foot board suspended from the ceiling. Armed with pneumatic attachments on the soles of her shoes, she’d attach her feet to the board and leave the minimal safety of the trapeze. With her head and hair hanging downward, she’d take steady suction-cupped steps backward and walk the length of the board, then turn and head back.

Aimée was daring, but she wasn’t crazy. The Human Fly protected herself with a safety net below, which was reportedly needed on frequent occasions. At least one other ceiling walker wasn’t as cautious, as a newspaper reported in 1883 after a performer’s strap broke and sent him falling 22 feet to his death in Indianapolis.

Ricky Jay wrote of several ceiling walkers in his wondrous book, Jay’s Journal of Anomalies. One of them, Richard Sands, was dubbed “The Air Walker at Drury Lane.” His boots suctioned him to the ceiling, and he always used a net. Well, almost always. Jay quotes an article from 1861 in which another performer described Sands’ demise: “After walking on the marble slab in the Circus, somebody bet him he couldn’t do it on any ceiling, and he for a wager went to a Town-hall, and done it, and broke his neck.” A section of the ceiling’s plaster had broken off during his attempt.

Shortly after, in November of 1862, Frank Buckland wrote about his observations of a performer called Olmar. Unlike Aimée and Sands, Olmar didn’t have suction-equipped shoes. He placed his feet inside rings hanging from a frame on a ceiling, 90 feet above the ground.

“These performances are most fraught with danger, imminent, literally, at every step. To go through them must require pluck more than human beings generally possess—nerves and limbs of iron, quickness of motion and thought, combined with steadiness and agility,” Buckland noted.

Olmar claimed to have spent eleven years learning the stunt and said the most difficult part was to “keep the blood out of his head” while dangling upside-down. He knew of no other performer who could—or wanted to—replicate his feat.