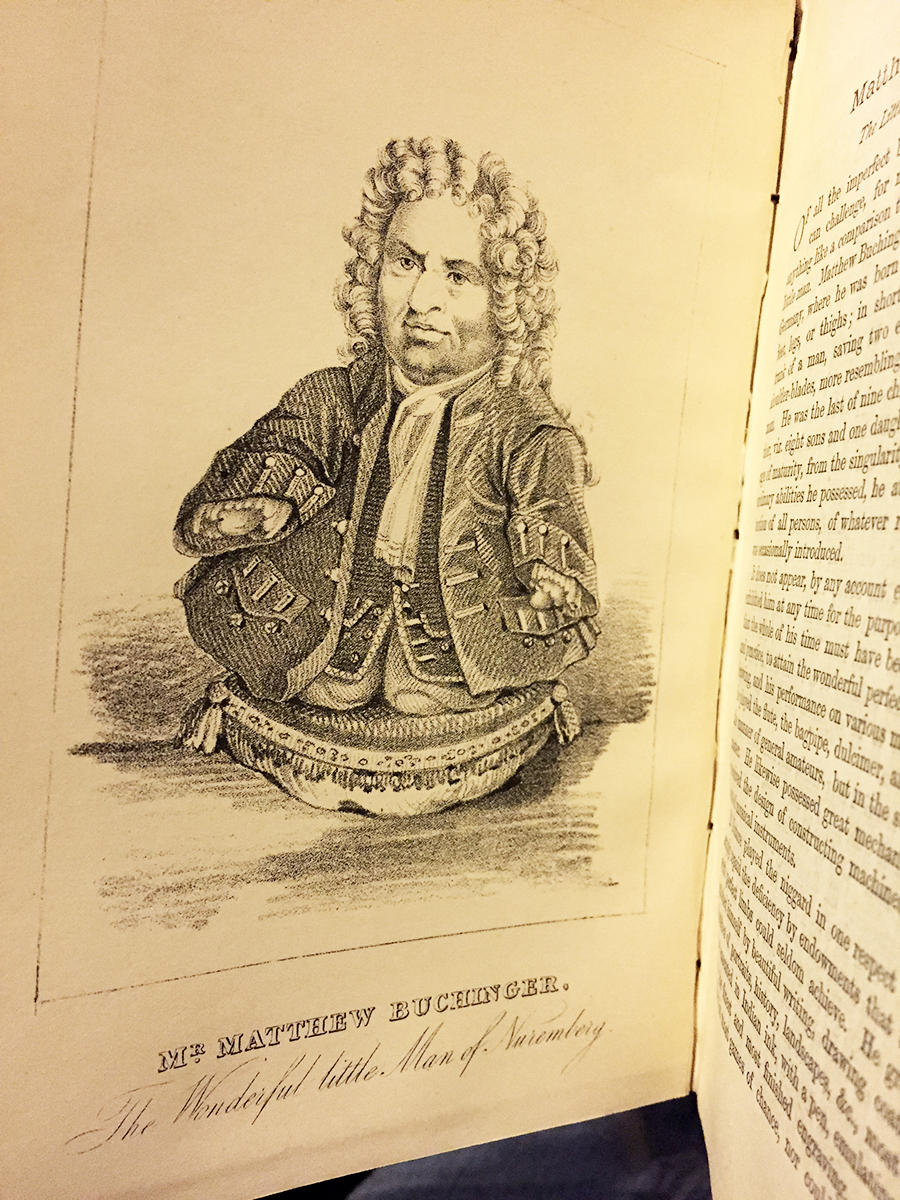

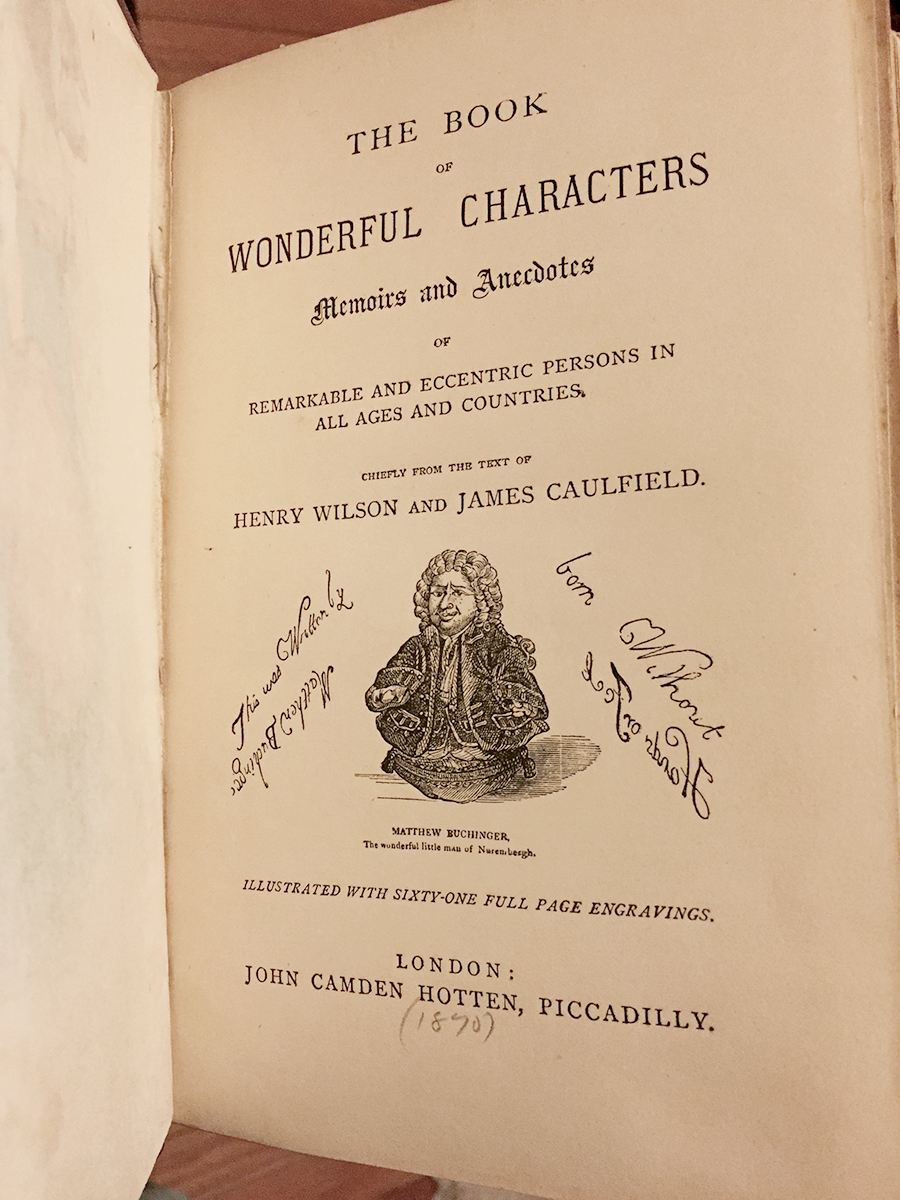

Matthew Buchinger on the title page of The Book of Wonderful Characters

Francis Battalia, The Stone-Eater.

Charles Domery, The Remarkable Glutton.

Barbara Urslerin, The Hairy-Faced Woman.

Francis Trovillou, The Horned Man.

And Floram Marchand, The Great Water-Spouter.

These are just a few of the people James Caulfield and Henry Wilson wrote about in their aptly titled 1869 book, The Book of Wonderful Characters: Memoirs and Anecdotes of Remarkable and Eccentric Persons in All Ages and Countries.

With all due respect to the Great Water-Spouter, the Horned Man, and the others, the most wonderful, remarkable, and eccentric person Caulfield and Wilson profiled was Matthew Buchinger, the Little Man of Nuremberg.

Buchinger was born in 1674 with no limbs, only small stumps. Yet he learned to play numerous instruments, performed magic, created masterful artwork, and fathered eleven children with four wives. At 29 inches high, he was indeed a little man, but he lived large.

His tale is reproduced below:

Of all the imperfect beings brought into the world, few can challenge, for mental and acquired endowments, anything like a comparison to vie with this truly extraordinary little man. Matthew Buchinger was a native of Nuremburg, in Germany, where he was born June 2, 1674, without hands, feet, legs, or thighs; in short, he was little more than the trunk of a man, saving two excrescences growing from the shoulder-blades, more resembling fins of a fish than arms of a man. He was the last of nine children, by one father and mother, viz. eight sons and one daughter. After arriving at the age of maturity, from the singularity of his case, and the extraordinary abilities he possessed, he attracted the notice and attention of all persons, of whatever rank in life, to whom he was occasionally introduced.

It does not appear, by any account extant, that his parents exhibited him at any time for the purpose of emolument, but that the whole of his time must have been employed in study and practice, to attain the wonderful perfection he arrived at in drawing, and his performance on various musical instruments; the manner of general amateurs, but in the style of a finished master. He likewise possessed great mechanical powers, and conceived the design of constructing machines to play on all sorts of musical instruments.

Matthew Buchinger, the Little Man of Nuremburg

If Nature played the niggard in one respect with him, she amply repaid the deficiency by endowments that those blessed with perfect limbs could seldom achieve. He greatly distinguished himself by beautiful writing, drawing coats of arms, sketches of portraits, history, landscapes, &c, most of which were executed in Indian ink, with pen, emulating in perfection the finest and most finished engraving. He was well skilled in most games of chance, nor could the most experienced gamester or juggler obtain the least advantage at any tricks, or game, with cards or dice.

He used to perform before company, to whom he was exhibited, various tricks with cups and balls, corn, and living birds; and could play at skittles and nine-pins with great dexterity; shave himself with perfect ease, and do many other things equally surprising in a person so deficient, and mutilated by Nature. His writings and sketches of figures, landscapes, &c., were by no means uncommon, though curious; it being customary, with most persons who went to see him, to purchase something or other of his performance; and as he was always employed in writing or drawing, he carried on a very successful trade, which, together, with the money he obtained by exhibiting himself, enabled him to support himself and family in a very genteel manner. Mr. Herbert, of Cheshunt, editor of “Ames’s History of Printing,” had many curious specimens of Buchinger’s writing and drawing, the most extraordinary of which was his own portrait, exquisitely done on vellum, in which he most ingeniously contrived to insert, in the flowing curls of the wig, the 27th, 121st, 128th, 140th, 149th, and 150th Psalms, together with the Lord’s Prayer, most beautifully and fairly written. Mr. Isaac Herbert, son of the former, while carrying on the business of a bookseller in Pall Mall, caused this portrait to be engraved, for which he paid Mr. Harding fifty guineas.

Buchinger was married four times, and had eleven children, viz., one by his first wife, three by his second, six by his third, and one by his last. One of his wives was in the habit of treating him extremely ill, frequently beating and otherwise insulting him, which for a long time he very patiently put up with; but once his anger was so much roused, that he sprang upon her like a fury, got her down, and buffeted her with his stumps within an inch of her life; nor would he suffer her to rise until she promised amendment in future, which it seems she prudently adopted, through fear of another thrashing.

Mr. Buchinger was but twenty-nine inches in height. He died in 1722.

For more on Matthew Buchinger, read Ricky Jay’s Matthias Buchinger: The Greatest German Living (Siglio Press). Jay, who has collected materials about and created by Buchinger for decades, shares the pieces he’s acquired and the stories behind them.