When Kenneth Arnold saw flying saucers in 1947 and launched a frenzy of UFO reports across the country, it wasn’t the first time such a phenomenon had occurred. A similar surge of sightings took place fifty years earlier.

As the turn of the century neared, marvelous new inventions like the telegraph, telephone, and x-ray amazed and excited the world. “This is an age of wonders,” wrote one newspaper reporter. “The marvels of human invention are multiplying, and we know not where to draw the line at the impossible.” So it’s not shocking that flying machines seemed a perfectly reasonable development. Or that people allegedly started seeing them by the end of 1896, when a wave of “airships” traversing the skies captured the country’s curiosity and imagination. They started in California and worked their way east, with newspapers along the way enthusiastically covering accounts of witnesses and frequently citing their “undoubted veracity.” This was about three years before the first Zeppelin appeared and the Wright brothers’ first flight wasn’t until 1903. Aside from hot air balloons, things just weren’t traversing the skies yet.

These airships, like the ones seen in November 1896 in Sacramento and the Bay Area, were typically described as “egg-shaped” or as having a “bird-like body” floating in the air with a “brilliant searchlight” and “fan-like wheels on either side” propelling them at about twenty miles per hour. Some witnesses claimed to have seen up to four passengers on one and heard them reveling in “merry song and laughter.” Others heard them speaking English as they expressed concern about their low elevation.

Naturally, there were those who tried to take credit. Several attorneys assured the press that they represented the inventors who were simply waiting for patents before staking their claim to fame with an official announcement about the airship. One of these lawyers, General William Henry Harrison Hart, used the airship to deliver his own political message, telling the San Francisco Examiner that he had advised his client to use the airship for war. “I believe that by means of this airship a great city could be destroyed in forty-eight hours.” The specific conflict Hart had in mind was the ongoing Cuban War of Independence, and the Spanish-governed Havana was the city to be destroyed.

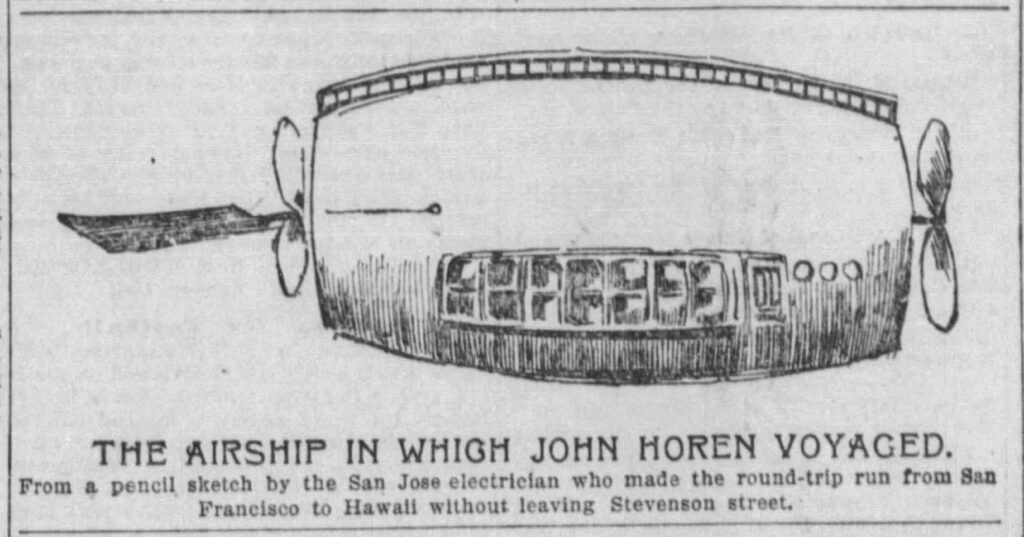

Where there were airships, naturally there would be people who said they flew in one. John A. Horen, the chief electrician of the San Jose Electric Improvement Company, was just such a person. Horen announced that he had installed his own patented “sparkling apparatus” in an inventor’s vessel, after which the two flew more than two thousand miles from San Francisco to Honolulu. This particular airship featured aluminum construction and stretched 163 feet in length and stood twenty-three feet high. It featured propellers at both ends, a “telescopic apron” in front, and curtained windows, from which he gazed through over Hawaii. The airship sounded fantastic, because, as his wife later told the Examiner, it was. Horen, she said, was a “star practical joker and was having some sport at someone’s expense.” During the supposed flight the chief electrician was, Mrs. Horen noted, “doing some of the soundest sleeping of his life.”

As the months went on the airships made their way across the south, the Midwest, and the northeast. Many sightings continued to find explanations through potential human ingenuity. Martian pilots were occasionally accused, though usually in jest, like when a Tennessee reporter remarked, “maybe some enterprising Martian has determined to surprise our earth, and has selected Tennessee’s Centennial occasion to make his appearance in spite of all the difficulties of ethereal passage.”

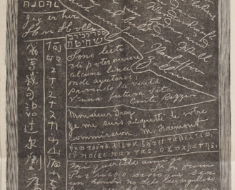

By mid-April, Martian airships had swarmed Texas. During a five-day span there were sightings reported in twenty-one towns. The most unusual incident took place in Aurora when the Dallas Morning News claimed a craft with apparent mechanical difficulties “collided with the tower of Judge Proctor’s windmill and water tank destroying the judge’s flower garden.” If the flying machine and floral fiasco weren’t shocking enough, the paper went on to say the sole pilot’s remains were “badly disfigured” but “enough of the original has been picked up to show that he was not an inhabitant of this world.” A local astronomer, T. J. Weems, declared the visitor was a “native of the planet Mars.” Scattered papers were supposedly found with mysterious hieroglyphics and remnants of the ship were “built of an unknown metal.” Though the body of such a being might be expected to be thoroughly examined, the article stated a funeral would be held the next day.

Were these “airships” actually early versions of flying machines? Or as some ufologists believe, were they from another world? In 1973, the United Press International ran a story about the International UFO Bureau’s attempt to exhume the buried Martian in Aurora. According to the group’s director, Hayden Hewes, this would allow them to “obtain some of the same type of unusual metal from either his clothing or bones that was unearthed at the well site when we checked it with metal detectors.” They’d spent three months checking the grave with metal detectors and gathering information. “We are as certain as we can be at this point he was the pilot of a UFO which reportedly exploded atop a well on Judge J. S. Proctor’s place, April 19, 1897.”

Members of MUFON (then the Midwest UFO Network) joined in on the investigation as well. The group, along with a local reporter, believed they found a fused nugget of aluminum alloy that didn’t exist on earth at the time. They also found a few residents who still remembered the event, like ninety-one-year-old Mary Evans who said the crash “certainly caused a lot of excitement,” though her parents wouldn’t let her join them at the site. At ninety-eight years old, G. C. Curley recalled two friends picking up pieces of metal from the crash and telling stories of a dismembered body.

Unfortunately for Hewes and other UFO believers, the Aurora Cemetery Association blocked the exhumation and prevented a possible end to the case, one way or another. So the story lived on and drew more curiosity seekers to the town in search of the spaceman’s grave. By 1979, Time magazine covered the bizarre incident and quoted eighty-six-year-old local historian Etta Pegues as saying the Dallas Morning News article was written “as a joke and to bring interest to Aurora.”

No Martian plummeted into a windmill—according to Pegues, Proctor didn’t even have a windmill—nor are there any town records of an airship (terrestrial or extraterrestrial) crashing in Aurora. As for Weems the astronomer, it turned out he was actually the local blacksmith. The once-prosperous town had fallen on hard times since a newly built railroad caused trains to completely bypass the area. So why not capitalize on the craze? If an airship crashed and a Martian pilot had been buried there, Aurora could become a tourist attraction and revitalize the economy. In that sense, the small Texas town was a precursor to Roswell.

While natural phenomena, hoaxes, and publicity stunts may have explained many of the sightings, it’s possible that some of the airships were actually just that, airships. Even though the first Zeppelin didn’t appear for about three more years and the Wright brothers’ first flight wasn’t until 1903, other inventors had been tinkering with the idea of conquering the air. In May 1896, Samuel P. Langley, who served as the secretary of the Smithsonian institute, boasted the successful unpiloted flight of his own flying machine over the Potomac River. The “aerodrome,” as he called it, derived its power from a steam engine and propellers. The fourteen-foot-long vessel traveled about a half mile at about twenty miles per hour. Fellow inventor Alexander Graham Bell lauded the test flight, claiming it moved “in one continuous gentle ascent as it swung around the circles like a great soaring bird” before its steam ran out and it “slowly and gracefully” came to a landing.

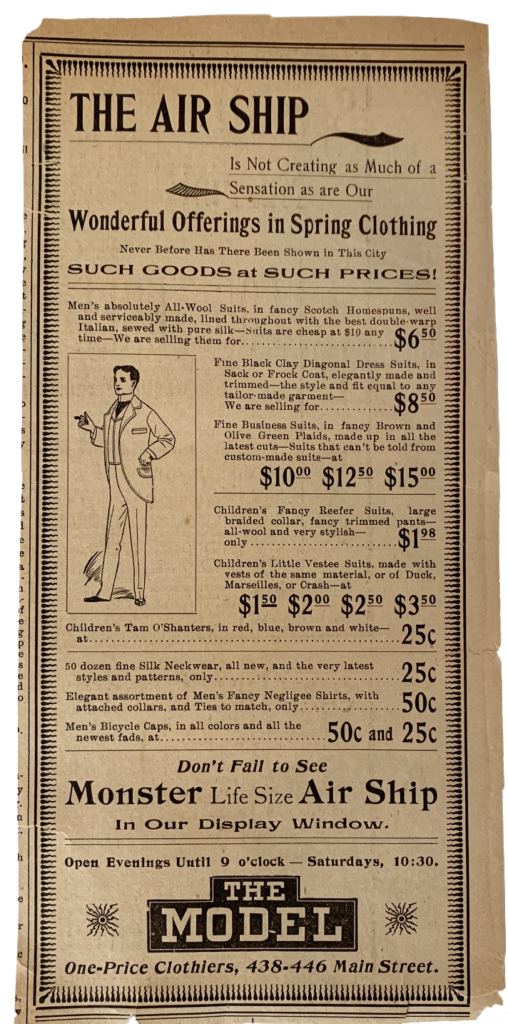

Whether Langley’s invention had been quietly improved upon over the next few months or not, the greatest phenomena may have been that of the media’s influence. They couldn’t get enough of the airship stories. It had mystery, drama, and in an age of invention, why not the real possibility of a flying machine? Some papers, however, made attempts to put the stories to rest. Just days after reporting Horen’s Honolulu story, the San Francisco Examiner called out its rival, the San Francisco Call, for leading the charge and perpetuating the sensation:

“Fake journalism” has a good deal to answer for, but we do not recall a more discreditable exploit in that line than the Call’s persistent attempt to make the public believe that the air in this vicinity is populated with airships. It has been manifest for weeks that the whole airship story is a pure myth. … It has had new airship fakes every day, each introduced with “scare heads,” assuring the trustworthiness of the story.

The countless reports and endless fascination of The Great Airship Flap of 1897, as it became known, serves as a microcosm of what was to come half a century later when people looked up to the sky and saw airships once again. Just more saucer-shaped this time.

This story was originally written for my book WE ARE NOT ALONE: The Extraordinary History of UFOs and Aliens Invading Our Hopes, Fears, and Fantasies (Quirk Books), and later ran in the January 2024 issue of the MUFON Journal.