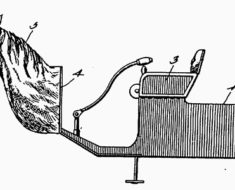

Table at Musée d’Histoire de la Médecine in Paris. Photo © Marc Hartzman.

At the Musée d’Histoire de la Médecine in Paris, on the lower level, past the cabinets filled with skulls, anatomical models, and antique medical instruments that cause physical discomfort just from looking at them, there sits a table. It’s no ordinary table. This table, in fact, is one of the most unusual pieces in the museum.

The card that sits upon it explains why:

“Made by Efisio Marini, Italian naturalist doctor, and offered to Napoléon III. This table is formed of petrified brains, blood, bile, liver, lungs and glands upon which rests a foot, four ears and sections of vertebrae, which are also petrified.”

Marini devoted himself to researching the petrification of corpses. He must have been quite pleased to share his accomplishments with the French leader when he gave the table as a gift in 1866. I do not know how pleased Napoléon III was to receive it.

The English writer, Thomas Adolphus Trollope, provided a colorful account of Marini’s work in his 1889 book, What I Remember. He remembered:

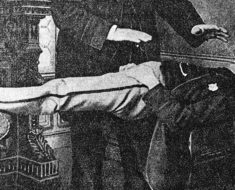

It was in the spring of that year that we went, taken thither by the Marquis d’Arcais, the well-known musical critic and editor of the Opinione, to see the very extraordinary preparations of the human body executed by himself. I think I may say that what we saw left upon the minds of all of us there present no shadow of doubt of the practicability of reducing the substance of the human body to the condition and consistency of marble, capable of receiving the highest degree of polish. We saw portions of the brain thus treated and resembling highly-polished madrepore; the liver assumed the appearance of the most splendidly colouring red marble. We saw, I think, a hand and fore-arm so preserved as to resemble accurately, save for a certain livid pallor, that portion of a living body. We saw a very beautiful and highly-polished table of various colours made from different portions of human flesh. I do not think we saw any complete body. This, however, was by no means all that Signor Marini could accomplish. He could, by a modification of his process, reduce the body, while equally preserving it and its colour, to the consistency of a sort of more or less elastic leather, in such sort that the limb would remain flexible. Of this kind of preparation we also saw specimens.

I suppose, but do not know, that the cost of the process would be considerably greater than that of cremation, or of the sums usually spent on our funeral obsequies. But if not, or if the expense of it could be rendered less than these latter, Signor Marini’s discovery would open to the imagination vistas of the most startling kind. What would be the result of so turning into marble all the individuals of all the future generations of me? How should we live in a world peopled by marble statues infinitely exceeding in number its living inhabitants?

Trollope poses an interesting question. Had Marini’s technique caught on, we could all be spending eternity as furniture.