In 1969, the world witnessed history when Neil Armstrong became the first man to walk on the moon. But there was a time, many years earlier, when the world was abuzz about men not only walking on the moon — but flying on it as well.

For one remarkable week in 1835, it was believed that an entire race of human-like winged people lived on the moon. It became known as the Great Moon Hoax, and indeed, it was great.

It all began with an article in the Tuesday, Aug. 25, edition of The New York Sun, stating that renowned astronomer Sir John Frederick William Herschel (who named seven moons of Saturn and four moons of Uranus) had observed life on the moon.

This was not a major scoop by the Sun, it was supposedly a reprint from The Supplement to the Edinburgh Journal of Science. The paper’s readers, however, didn’t know that publication had gone out of business several years earlier. Nor did they suspect that a creative editor, Richard Locke, fabricated every detail.

The findings stated wondrous forms of plant life and wildlife were living happily on the moon. The creatures included a monstrous blue unicorn with a beard like a goat and tailless, but talented, beavers that walked on their hind legs, lived in huts and built campfires.

Additional discoveries were reported each day that week, with a growing readership and word spreading across the country and the globe. It was, as one might expect, a true sensation.

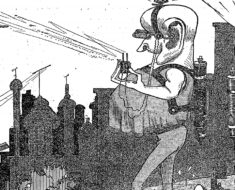

Friday’s edition announced the discovery of the flying humans, dubbed “man-bats.” These alleged four-foot tall beings were covered with short, glossy, copper-colored hair — except for on the face. Their wings were composed of a thin membrane and had no hair.

Herschel’s powerful telescope offered even further details to report:

The face, which was of a yellowish flesh color, was a slight improvement upon that of the large orangutan, being more open and intelligent in the expression, and having a much greater expanse at forehead. The mouth, however, was very prominent, though somewhat relieved by a thick beard upon the lower jaw and by lips far more human than those of any species of the simis genus.

These short, unattractive flying folks were also quite chatty and expressive with their gestures: “the varied actions of the hands and arms appeared impassioned and emphatic.”

As the excitement spread, there were those ready to take action. One group of women from Springfield, Mass., wrote to Sir Herschel asking how they could help spread the gospel to these pagan man-bats of the moon.

Scientists from Yale University were reportedly sent to the Sun to study a physical copy of the journal. But Locke sent them from one office to another, dodging them until they finally returned to campus as curious as they were before they left.

Although it all sounds ridiculous today, in 1835, knowledge of the moon was lacking and the belief in extraterrestrial life, including lunar life, was commonplace.

In the October 1826 issue of the Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal, an anonymous author wrote that German astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Matthäus Olbers “considers it as very probable that the moon is inhabited by rational creatures, and that its surface is more or less covered with vegetation,” and that based on observations made through his telescope, fellow German astronomer Franz von Gruithuisen “maintains that he has discovered… great artificial works in the moon, erected by Lunarians.”

Gruithuisen also proposed that because the moon was closer to the sun, its jungles grew faster than those in Brazil and that the Lunarians held fire festivals, which caused the bright caps on Venus.

By the end of that extraordinary week, it was reported that the Herschel’s telescope was clumsily left facing the sun and that a hole had been burned into its reflecting chamber, preventing any further observations of our new winged friends on the moon.

The hoax finally came to light when Locke privately told a fellow writer at the Journal of Commerce, and word traveled to the Sun‘s publisher. The story, however, proved entertaining — and that’s just how people took it. Circulation of the paper remained up in the months that followed.

Locke publicly denied that he’d concocted the entire account himself.

© Marc Hartzman