When in Rome, well, when in Rome you will be surrounded by tourists and tchotchkes for all those tourists to buy. But away from the Colosseum and the Trevi Fountain there’s another fascinating attraction worth seeking out that requires no “Skip the Line” tickets: The crypt of the Capuchin friars at the Church of Santa Maria della Concezione.

Before entering the crypt, you venture through a museum featuring various old books, church ritual tools, and paintings, including Caravaggio’s Saint Francis in Meditation, circa 1603.

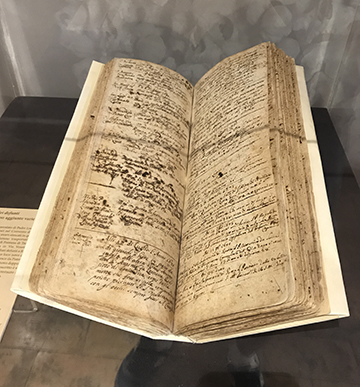

Register of the Dead, at the museum at the Church of Santa Maria della Concezione.

Once you’ve passed through the museum exhibits, you encounter the Register of the Deceased, 1608-1732, positioned at the entrance of the crypt. Names of the early Capuchin monks resting in the crypt are recorded within—with those prior to 1631 having been transported from an old friary in San Bonaventura. This required 300 wagonloads of bones from the early friars.

The crypt is a stunning, macabre sight.

Inside, there are six rooms, five of which feature ornate displays created from the bones of more than 4,000 capuchin monks lining the walls and vaulted ceilings. Several monks remain fully in tact with their robes. It’s their robes, in fact, that earned them the name “capuchin.” The term comes from the Italian term cappuccino, meaning “pointed cowl,” which described the hoods of the monks’ robes (the coffee beverage of the same name comes from the color of their robes).

The various designs include eight-pointed stars created from jawbones and vertebrae, a winged skull within a circle of small bones, floral motifs, and a rosette fashioned from seven shoulder blades, vertebrae and foot bones.

Through the mid 1700s, there were reportedly only stacks of bones in the crypt. The remarkable ornamentation of them wasn’t described until 1775, when the Marquis de Sade visited and wrote:

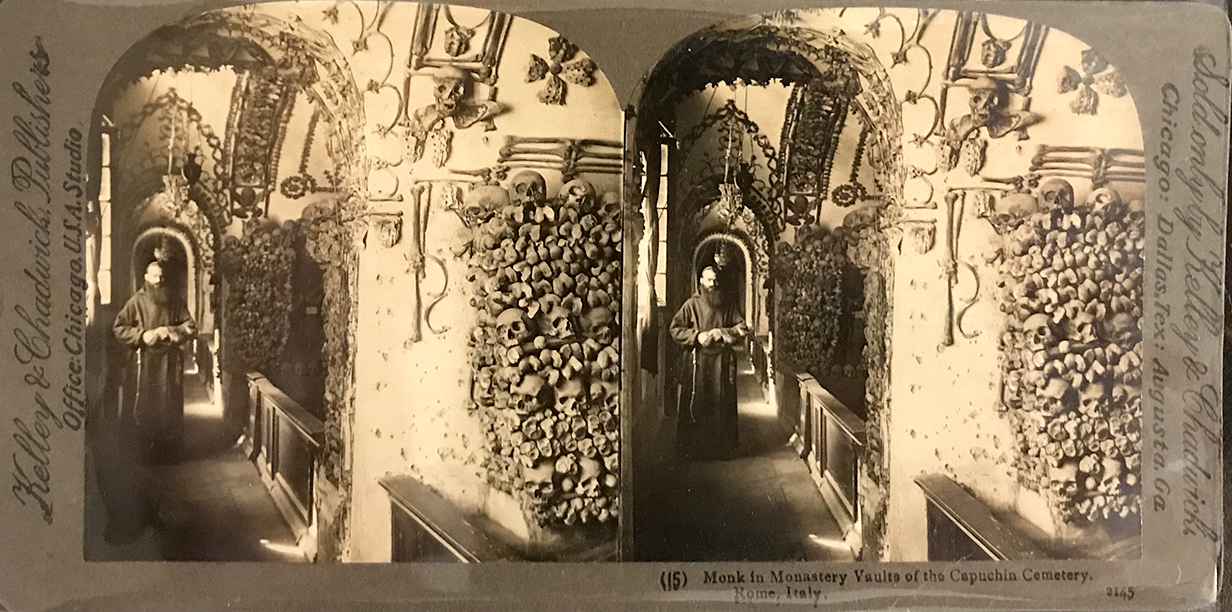

Capuchin friars in the crypt at the Church of Santa Maria della Concezione.

A German priest of this house has fashioned a funerary monument worthy of an English mind. In six or seven small rooms, one beside the other, he has made some niches, vaults and ceiling ornaments of regular and pleasing design, lamps, crosses, etc., the whole made out of bones and skulls. In each of the niches or under every arcade there is a well preserved skeleton, placed in varying attitudes, some reclining, others in the act of preaching, others at prayer. All these skeletons are dressed in the Capuchin habit: some are bearded. Never have I seen anything more impressive, and to make it more so, it seems to me, one should visit this monument, not by day but in the light of the funereal lamps that are within. But the need to keep the air in this cavern constantly purified makes them keep all the windows open, so that the great light that reigns there always abates the horror. In each of these small rooms are distributed, like stones in a garden, the several tombs of these good friars. However, the sight of death surrounding them on all sides does not prevent them from being as cheerful as in the rest of Europe!

Stereoview of the Capuchin crypt, circa early 1900s. Hartzman Collection.

According to the booklet, The Capuchin Cemetery, by Rinaldo Cordovani, there have been numerous claims over the years accounting for the intricate and unique designs of the crypt. Some have said it was the work of a clever hermit, or a criminal hidden away in the crypt by merciful monks. Cordovani says the most common theory is that the crypt’s designs are the work of Capuchins who fled France during the Reign of Terror. However, this would have been nearly twenty years after the Marquis de Sade’s description.

Cordovani suggests that “the present arrangement is the work of one of the Capuchin artists who were habitually present in the friary, helped by various craftsmen, also friars, who lived with him in the large community in the Piazza Barberini as it then was.”

Regardless of the true origins, the bones of these monks have turned death into a work of art and beauty. What better way to rest in peace?

Stereoview of the Capuchin crypt with monk. Hartzman Collection.

![Charlie Chaplin's grave. By Giramondo1 from Vila Isabel, Brasil (Charlie Chaplin, R.I.P.Uploaded by Manoillon) [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.weirdhistorian.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Charlie_Chaplin_grave-crop-235x190.jpg)