A fear of death is quite a natural thing. After all, the idea of our existence ceasing to be is quite unsettling. So is the notion of our flesh rotting away and being eaten by worms and other bugs while lying in pitch blackness in a box six feet under.

Even more terrifying is having that happen while still alive.

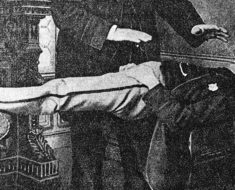

Sometimes the gravediggers worked when then shouldn’t have. Photo from the Marc Hartzman Collection.

It wasn’t long ago that premature burial was a distinct possibility. As recently as the 18th and 19th century, cholera victims often fell into comas and were presumed dead. They were then quickly buried to avoid any further spreading of germs. In other cases, early doctors misdiagnosed patients as dead, particularly in cases of catalepsy.

Such disturbing cases even inspired Edgar Allan Poe to write The Premature Burial in 1850. In it, he documents several instances of live burials before launching into a narrative of his own fictitious interment.

This life-and-death problem gave rise to a new industry: safety coffins.

Starting in the late 1700s, innovative coffin makers began to develop ways for the “dead” to signal the living from within their casket, such as adding a bell atop the grave that could be rung from below.

In August of 1868, a German inventor, Franz Vester of Newark, New Jersey, took such safety precautions to a new level. He received a patent on a unique coffin that allowed the not-quite-dead-yet inhabitant a chance to climb right out of the grave, if able, or to signal for help if not. It even offered storage space for food—so if you weren’t dead, you wouldn’t end up that way from starvation.

An article from the October 16, 1868 edition of The Public Ledger described the device:

This invention consists of a coffin constructed similar to those now in use, except that it is a little higher, to allow of the free movement of the body; the top lead is moveable from head to breast, and in the case of interment is left open, with a spring attached for closing the same, under the head is a receptacle for refreshments and restoratives.

The most important part of the invention is a box about two feet square, resembling very much a chimney, with a coves and ornamental grave work on the top. The box is of sufficient length to extend from the head of the coffin to about one foot above the ground. The cover is fastened down by a catch on the inside, and cannot be unfastened from the outside. Just below the cover is a bell similar to those used on street railway cars, with a cord appended, which, upon being pulled, sounds an alarm, and at the same time a spring throws the cover from the ‘chimney-box.’

Then if the person on the inside have sufficient strength, he or she can take hold a rope suspended from near the top of the chimney-box, and, with the assistance of cleats nailed to the sides, ascend to the outer world; or otherwise the individual can rest at ease, munch his lunch drink the wine, and ring the bell for the sexton to come and assist him out.

Franz Vester’s safety coffin, designed to save anyone who might have been buried alive.

Vester’s creation, from the sound of it, seemed to turn a horrifying experience into a relaxing moment of peace and quiet.

In October, Vester offered to demonstrate just that. More than 600 alive-and-well Newark spectators paid 50 cents to witness the life-saving contraption. Gravediggers prepared a six-foot hole and Vester climbed into his coffin, ready to be lowered into the ground. The “chimney-box” was put in place and then the gravediggers grabbed their shovels and buried the inventor alive.

Vester had planned to stay buried for a few hours, but the crowd was anxious and so a signal was given for the showman to emerge.

“A minute after Mr. Vester unaided, stepped out of his living grave,” the article reported, “with no more perceptible exhaustion than would have been caused by walking two or three blocks under the hot sun.”

Vester’s was only one of many new designs. In Jan Bondeson’s 2001 book, Buried Alive: The Terrifying History of Our Most Primal Fear, he describes later patents that were more advanced in their technology, including electrical signals triggering flags, bells, rotating lights, a heater and even a telephone. Regarding the latter, Bondeson shared the story of a Louisiana woman, Mrs. Pennord, who was buried with a telephone connected to the cemetery keeper’s house in 1908.

Of course, today, we could all be buried with our phones. We could Facebook Live the whole experience as we wait for gravediggers to receive our texts and rescue us.