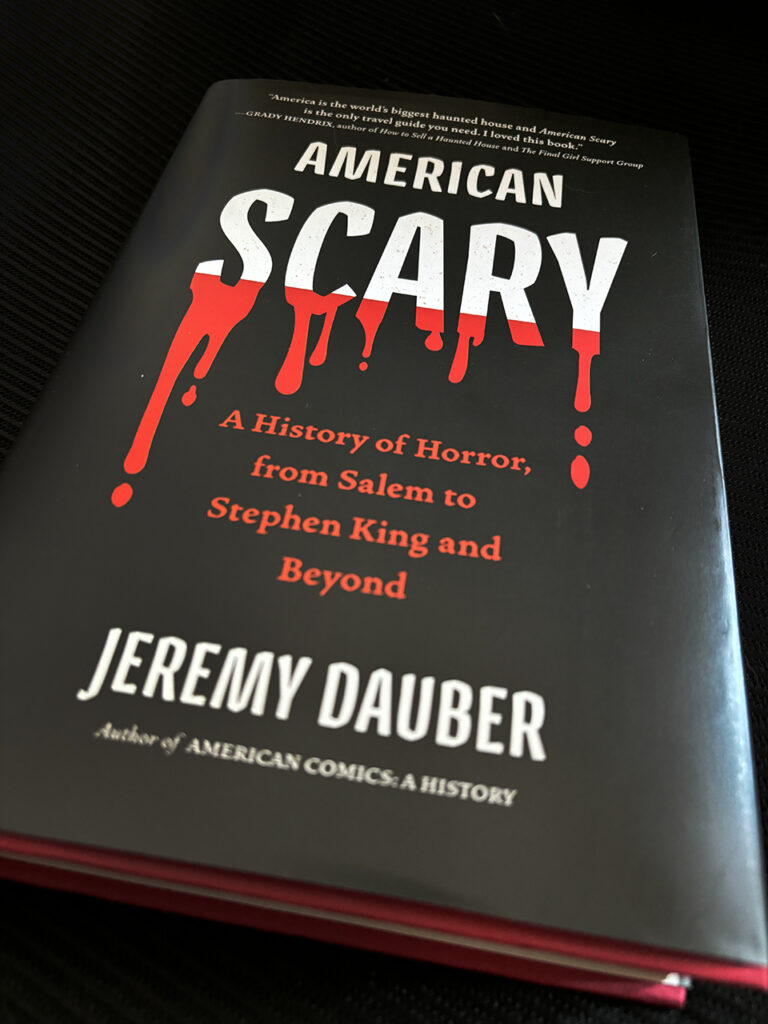

It’s Halloween season. But whether it’s October or any other month, what is it that causes us to invite fear into our minds? To welcome the slashers, zombies, vampires, ghosts, creepy creatures, and crazy people that fill our favorite horror movies and scary stories? Author Jeremy Dauber, a professor of Jewish literature and American studies at Columbia University, brilliantly dissects the history of American horror in his new true treasure trove of terror, American Scary: A History of Horror, from Salem to Stephen King and Beyond (Algonquin Books/Hachette).

The book delves into the way horror has evolved over four American centuries, reflecting society from the colonial era to the present and showing how many of our fears have held constant. I spoke with Dauber about the phenomenon of horror and several of his personal favorites. Our conversation follows:

Weird Historian: There’s a whole lot packed into this book! How long has it been in the making? Is this just the culmination of a lifetime of watching movies, reading books and watching TV, or is it something you of dove into for the purpose of the book?

Jeremy Dauber: Ever since I was a kid, I’ve been interested in certain parts of the horror experience, trying to figure out what I was willing to read or watch and not be too scared about, and trying to figure out why I like it. I was a big Stephen King fan from early on, and I got into horror comics and things like that, but then I started teaching about it and decided, okay, I can write about this. And then the last few years have been a much more intensive immersion in both stuff that I had never seen before because I was too scared, or stuff that I had seen. But it had been a while, and was thinking about it with new eyes, so to speak.

WH: Yeah, that makes sense. You have to look at it fresh and with a new lens. What is it about horror that fascinates you so, so specifically?

JD: One of the main things that I found so interesting about it is that it really is a kind of X ray into a society. If you’re really trying to understand what makes a particular society, a particular culture tick, one of the best ways—not the only way—but one of the best ways of doing it, is to find out what scares them. And so looking at what really unsettles or disturbs or makes a country’s culture anxious is an interesting way to see what’s troubling them and what’s making them tick. So that was a lot of what really drew me to it as a subject of both studying and writing a story about it, and some of it was just that I really feel like there are very few kinds of works of art that really established such a visceral connection with their audience. You can go see an amazing painting and you’re going to be moved, and you can listen to a poem, but horror is one of those things that really elicits an involuntary reaction from you. That’s how powerful it is, right? I mean, you scream, or you jump, or you gasp, and investigating that kind of power was also something that was fun to do.

WH: It does really stick with you more, doesn’t it? If you’re scared, the reaction lingers more than feeling moved by a poem, for example, right?

JD: I agree with that. There are certainly poems that you come back to, they’re something you think about that really can change your life, so I’m not down on poems—of course, there’s scary poems, too—but there are ways in which you are watching a movie and then it literally haunts you. Let’s use that horror word, right? I mean, you can come back and you’re like, “Well, I know it’s not real, but on the other hand, I’m still going to check under the bed. I’m still going to kind of look at the closet before I go to bed.” Even if nobody’s around, or maybe especially if nobody’s around. And I think that sometimes that speaks to just the way in which horror activates these universal fears in all of us, and sometimes it’s about particular things that are going on in society now that that movie or that book are really pointing at and prodding at.

WH: It is a reflection in a lot of ways. You included Black Mirror in your book, which, to me, is the only thing that’s come close to The Twilight Zone in terms of that genre. It’s so well done, but that’s truly reflecting on right now—like a peek 10 minutes into the future.

JD: That’s right. A lot of horror is about technology, whatever period that technology is new in, there’s horror. And when you’re telling the story of America, you have horror of the new industrial machines, right? That’s new. You have horror of the new anonymity of cities, and then horror of the atomic bomb, right? You have horror of space exploration. All of these things allow for new kinds of ways of being afraid. But in that sense, they’re also continuous, because there’s always something new, and we’re always afraid of it. But I think you’re right, Black Mirror does a great job of taking the horror of our particular moment, these phone screens, these things we carry around our pockets, these algorithms, it’s a great articulation of those particular new technological fears.

WH: Yeah, it’s very much right now. Do you have an opinion on what the best decade for horror was?

JD: That’s a great question. I generally say that there’s the cyclical kind of quality, let’s say—so I think this is cheating a little bit—but I love the ‘30s, the ‘50s, the ‘70s into the ‘80s, and\ the last 10 years or so, which have been amazing. I think, given sort of my own interests in predilections, I like the ‘50s movies in some ways the most. But that’s just my own personal taste. I think movies from the ‘70s and movies now are just incredible. They’re just amazing.

WH: My next question was going to be about the recent movies. There’s been quite a resurgence in the genre within the last 10 to 15 years or so. What’s led to it, and do you have any particular ones that stand out the most for you?

JD: Well, I’ll tell you a little story. I am of an age where I went to see The Blair Witch Project, which is from 1999, in the movie theaters. So, right before this period starts. And I went to see it in this rundown movie theater, and I was the only person in the theater, like the single only person in this big theater that was kind of broken down. It was a horror venue itself, right? And I was just overwhelmed and paralyzed with fear. So The Blair Witch Project really stamped the beginning. Another phenomenal movie that was a doorway to this new period was The Sixth Sense, which comes out the same year. I saw it in a big crowd, and it was a great movie, it’s a phenomenal movie, but, but it didn’t have that same effect. But one of the things about The Blair Witch Project is it’s the found footage genre. It’s this bunch of student filmmakers who can carry around a camera and do stuff in a lo-fi way. Obviously, that’s the movie within the movie. But it also speaks to the idea that lots of people can make horror movies now. They don’t have to necessarily go through the studios. They can post things online. They can do them much more cheaply. The equipment is cheaper, it’s easier to operate. And so you really have the opportunity of letting a thousand flowers of more individual sensibilities bloom. Also, at the same time, you have these people who, thanks to the internet and before that, DVDs and video stores, are easily able to see so much more than people of previous generations ever were. So they’re really able to become horror aficionados in a way that was very, very difficult for other people. So they have the raw input, and then they have the kind of idiosyncratic creativity, and then they have the places to put them.

WH: Very true. Throughout the decades you’ve mentioned, do you have an all-time favorite horror film and/or novel?

JD: Thank you for bringing up both, because I think there’s so much great literature as well as so many great movies. So what I think my favorite horror movie is, it sometimes depends on the day, and the mood that I’m in, but I think the movie that’s the most American horror movie, the one that says the most about America, in some ways, is that 1950s movie The Night of the Hunter, which, for people who don’t know, it’s this movie that’s based on a novel, which is based on a true crime story about what we might call a lonely hearts killer. Somebody who marries women and then kills them. And the movie is set during the Great Depression. And this particular lonely hearts killer, who is played by Robert Mitchum, is a psychopathic preacher, who’s also trying to get this treasure that he knows is somewhere on the premises. It is the combination of a dark fairy tale with a genuinely terrifying main character, and a real exploration of what the dark side of the American existence is. Every time I see it, I’m just amazed at how good it is. That, to me is the most American movie, and on most given days, it’s probably my favorite. And if you haven’t watched it out there. I envy your first watch of it. I really think it’s just tremendous.

In terms of my favorite horror novel, you know, I gotta say it’s this is not so surprising, perhaps, given the early traumas of my upbringing: it’s a Stephen King novel. And this one also shifts from day to day, but I recently reread It, and I actually do think that it is his great work. It says everything it needs to about childhood in America, and what it means to be afraid in America. I just love it. If you’ve only seen the movie, go back and read the book. It’s only 1,100 pages.

WH: One last thing, because this is Weird Historian, what is your favorite all-time horror film in the category of weirdest?

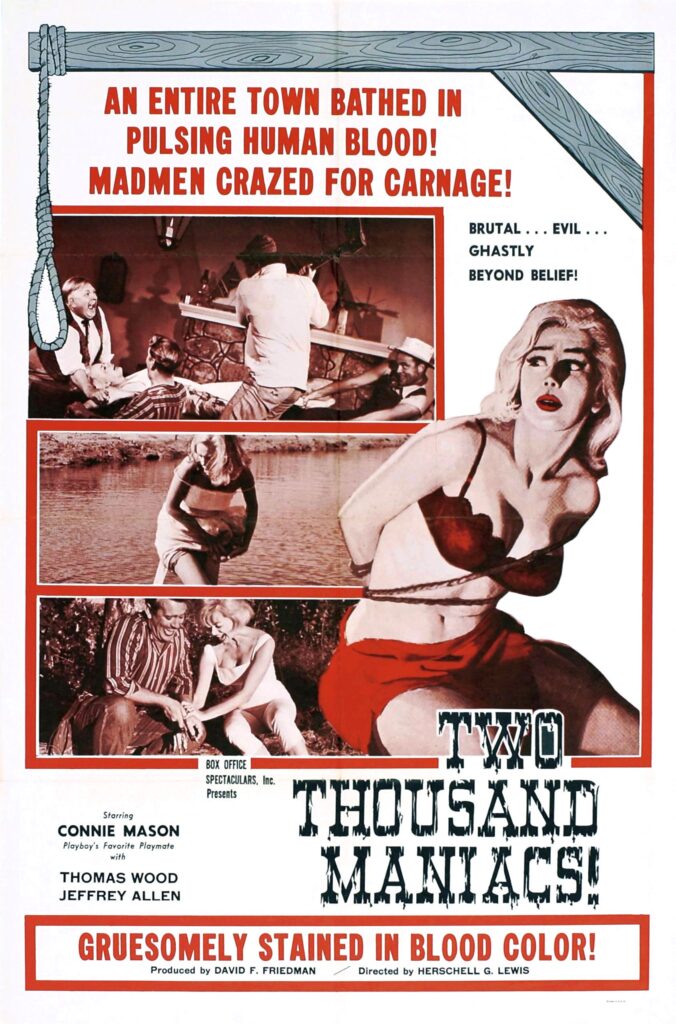

JD: Oh, weirdest. That’s a great question. So the weirdest horror movie that is coming to my mind—something that we would all recognize as horror—is probably Two Thousand Maniacs! Have you seen that?

WH: No.

JD: So Two Thousand Maniacs! is made by this guy who is considered an early pioneer in gore. And basically what the movie is is it’s sort of like Brigadoon, but with a psychopathic, bloody set of murders. So it’s this southern town that appears from 1964 that has been totally slaughtered by the Union during the Civil War. They disappear for 100 years, then they come back and they kill any unwary northern travelers who come in their way. And it is weird and bonkers and incredibly gory, and also has some very interesting things to say about that prime period of the civil rights movement in the south, of this very, sort of complicated resentment between the north and south. It’s a town full of ghosts, and they’re murderous, so it’s really interesting in that way.

The weirdest movie that pokes fear in the American public is a movie by John Waters called Pink Flamingos, which is maybe the most disturbing American movie ever made, bar none, right?

WH: Definitely a weird one.

JD: It’s a weird one, and it is not for the faint of heart or stomach. I would not necessarily recommend it, and it’s not because it is scary, but it really is just a challenge to everything about society in these extremely anxiety producing and alienating ways. So that’s certainly weird. No question about that.

WH: Agreed! American Scary is an amazing book, so thank you for putting it together. I wish you the best of luck with it.

So, what’s your favorite horror movie and book? Mine are The Changeling (1979) and Bram Stoker’s classic, Dracula. Whatever yours are, pick up American Scary, and you just might discover a few dozen more favorites.