Sometimes prankish ghosts act like twelve-year-olds because, well, they are. Such was the case in January 1900 at a house in Paterson, New Jersey. Jacob and Elizabeth Stahl filled their modest home with seven children, yet apparently found room for one more tenant—a ghost who’d moved in after Christmas.

Since then, dishes moved across the table, bed sheets were tossed around the house, overturned tables and chairs unsettled rooms, and pieces of wood, lumps of coal, and other random objects were hurled at the children and anyone else in sight. Elizabeth, a woman of “unimpeachable veracity” had spotted ghostly hands at her windows and even claimed to have seen chairs dance.

What suddenly caused such a devilish spirit to overtake the house? No one had died within its walls since it was built. And as member of the enthralled media noted, it hardly fit the stereotype of a haunted house:

“The Stahl house is not the kind of place which a real bona fide, self-respecting bogey would select to haunt. Within easy gliding distance there are several dignified and gloomy mansions, and on the hillside, in fair sight, stands a most delectable deserted house with broken windows, flapping shutters and other desirable appurtenances.”

Yet, the action in the Stahl house was undeniable and a good night’s sleep was nonexistent. Police investigated but found nothing. Clergymen tried to exorcise the unruly spirit, but it showed no fear of their holy words.

By mid January curious neighbors flocked outside the home hoping to see the ghost for themselves. One of them, a “temperate and courageous” mechanic named August Post, spent the night in the kitchen and reported numerous encounters with the spook. As he sat in the kitchen smoking a clay pipe he witnessed cutlery rise from the table and jump to the stove, all to the sounds of thumps on walls and doors. Post swore no one was around. When he momentarily stepped out of the kitchen, he found his pipe broken on the floor and his stem missing. He blamed it on the devil.

“Why his Satanic Majesty should spirit away a pipe stem without the bowl is a question he prefers to leave to persons more deeply learned in theology than himself,” noted the New York Sun.

Post and others chatted about the strange happenings at the bar across the street, where plenty of spirits of the alcoholic variety were consumed. With no satisfying explanations being offered, the chatty neighbors began coming up with their own. The popular theory centered on Jacob’s first wife, who’d died eight years earlier and left her husband with three small children. Stahl married Elizabeth just a month later and bought their suddenly haunted home with money left from his deceased wife. Was her spirit lashing out at her barely grieving husband and his new bride?

Martin Curley, the saloon’s owner, didn’t believe in ghosts, poltergeists, or anything of a supernatural nature, so he ventured over to the Stahl home to see what all the fuss was about and to find some answers. Instead of solving the mystery, he came back with a fresh supply of stories that would undoubtedly be good for business.

“What I saw this morning, I never want to see again,” he told a reporter from the comfort of his bar. “Why, you can stand in this store and hear the rapping from across the street. This morning I stood in the kitchen and saw knives taken from the table and thrown on the stove. I saw one of the children thrown to the ground.”

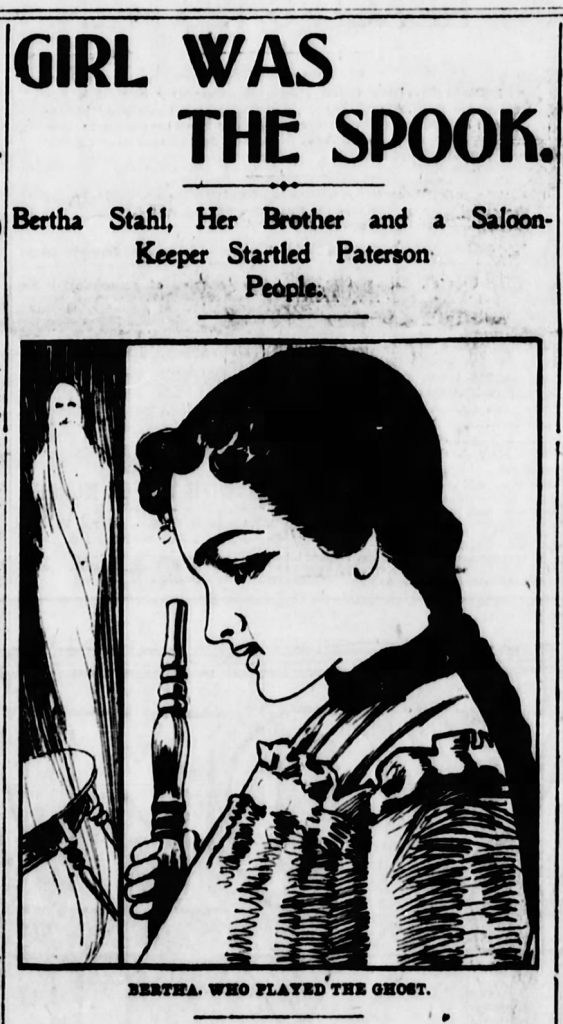

That child was twelve-year-old Bertha. Despite the shove from an unseen hand, Bertha wasn’t afraid of no ghost. Nor was she afraid of any of the investigators or neighbors who’d flooded their house. Until, that is, Arthur W. Bishop, visited.

Bishop was President of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. Apparently reports of the attack on Bertha had gotten his attention, along with the potential threat to the six other young children exposed to the rambunctious spirit. Bishop asked Elizabeth to be left alone in the spook-infested dining room, where a rung of a chair, the head of a dust brush, and some toy blocks had just been tossed to the floor. As Mrs. Stahl tidied up, Bertha snuck into the room, picked up the chair rung, and tossed it at a wall before slipping out of sight. Sneaky, but not sneaky enough. Bishop asked Elizabeth to bring Bertha into the room. Reluctantly, the young girl sat down with the investigator.

“Now, Bertha, do you know what sin is?” he asked. “If you tell a lie, do you do right?”

Bertha looked away, fidgeting with her fingers.

“Well, tell me this. What made you throw that stick against the wall? Come, now, tell me.”

Bertha remained mute for a moment, then finally answered, “I did not know that the stick left my hand.” She confessed to having made the other noises as well.

Shocked by such an admission, Elizabeth came to her daughter’s defense citing what a good girl she was. But as her discussion with Bishop continued, he pointed out that, based on the stories she’d shared, Bertha always seemed to be around when the “ghost” made an appearance. Bishop made the young girl promise to stop scaring the neighborhood with her noises.

Elizabeth wasn’t entirely convinced. Even though Bertha admitted to being the culprit, she claimed her daughter had no control over her actions. She invited a Spiritualist, Mrs. A. J. Phillips, to the house to visit with Bertha. Phillips questioned the puckish girl and determined she was not a medium, but “had a great deal of mischief in her eyes.” The Stahls still weren’t buying it, so they sent Bertha to stay with their reverend for a few weeks hoping he’d drive the evil spirits away.

No reason for Bertha’s behavior was given, though she may have resented her stepmother or maybe wasn’t happy with her Christmas gifts. Or maybe she was just a twelve-year-old enjoying a little extra attention in a small house full of six other kids. That could be scary for anyone.

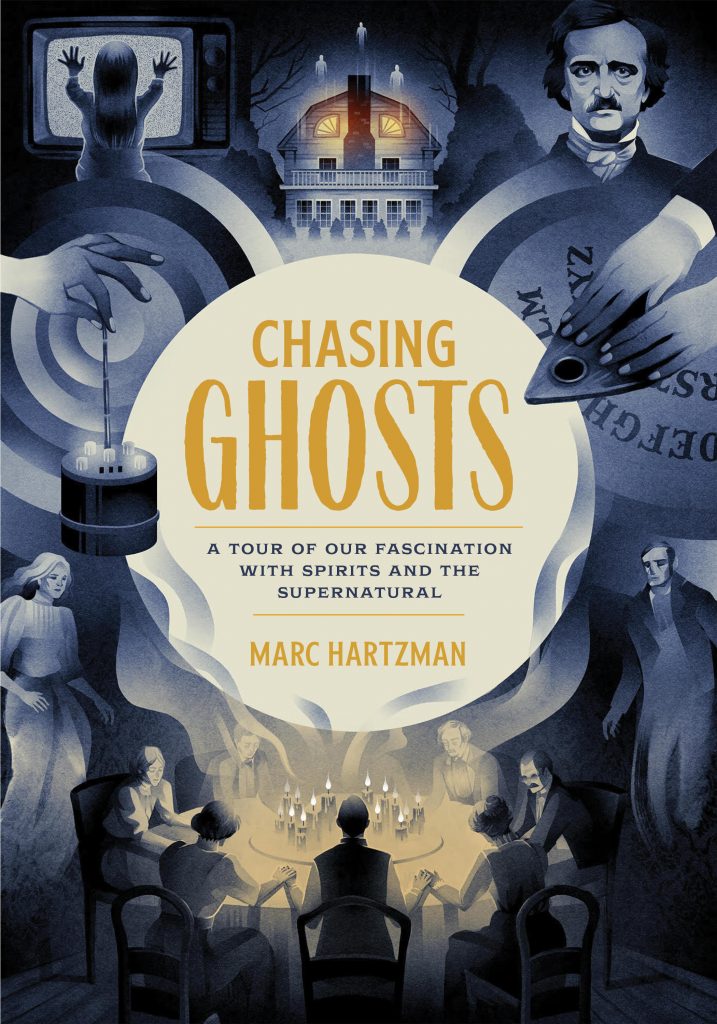

The above story was originally part of my new book, Chasing Ghosts: A Tour of Our Fascination With Spirits and the Supernatural (Quirk Books). Pick up a copy for many other incredible tales of ghosts and the paranormal!