If you’ve ever watched an old western, or a movie about the Old West, you’ve seen two men in their cowboy hats settle a dispute by walking ten paces, drawing their gun, and firing.

Back East, Alexander Hamilton, of course, is well remembered for his 1804 pistol duel with Aaron Burr in Weekhawken, New Jersey. (As a history refresher, Burr won, and Hamilton died from the gunshot wound a day later.)

The duel goes back hundreds of years and served as a means of resolution when one’s honor was challenged. But by the twentieth century, duels had been largely outlawed. Yet, the 1900s still saw its share of violent conflict resolutions.

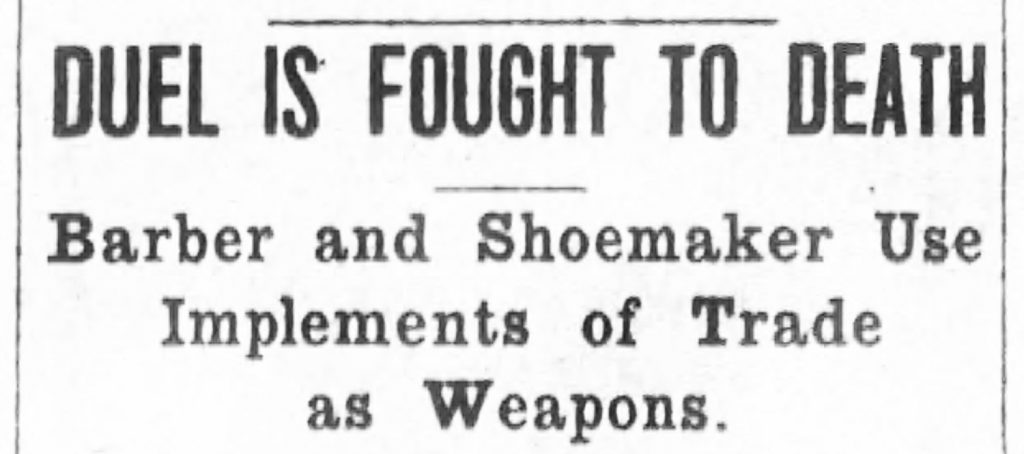

Some of them created strange headlines, such as the one seen above about an angry barber and shoemaker. In October of 1930, Joaquin Botsch, the barber, and Manuel Lopez, the shoemaker, didn’t choose guns or swords to end their argument. They chose tools of their trade. Botsch armed himself with a razor, and Lopez with a leather knife.

The cause of their dispute is unknown, but whether Lopez got a bad haircut or Botsch didn’t like his shoes, they found a quiet spot in Alto Cedro, Cuba, and fought it out. After fifteen minutes, Botsch and his mighty razor won. Lopez lost his life, and the barber was arrested for murder.

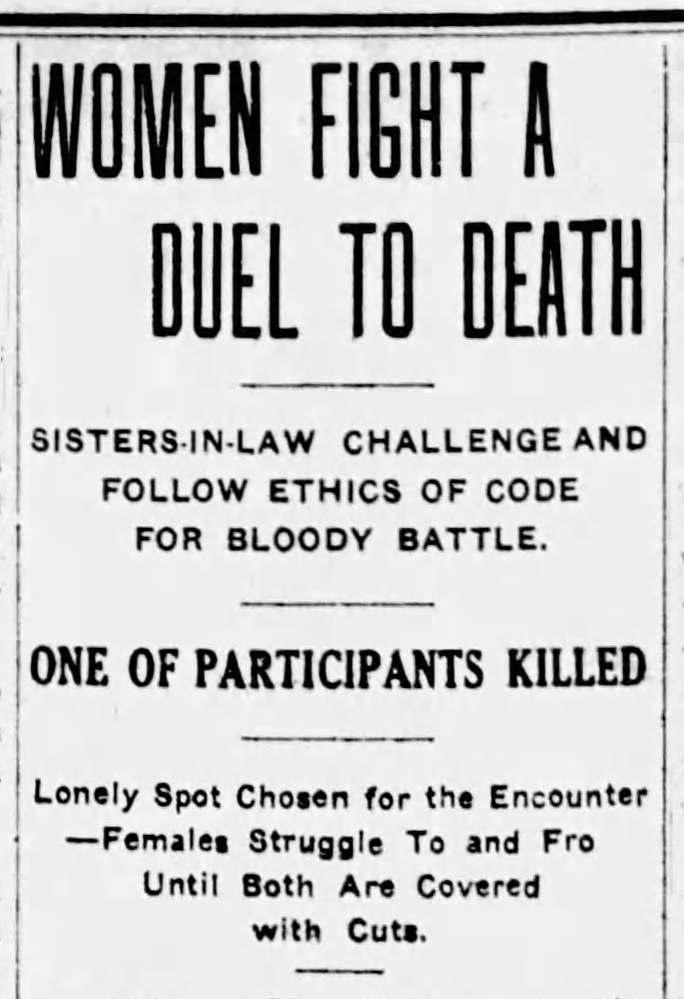

In 1909, readers of Michigan’s The Sebewaing Blade were informed of sisters-in-law—Mrs. Graham and Mrs. Crabtree— who settled their issues with sharpened bowie knives. The duel, which took place in “a lonely spot in the Ozark mountains” near Gainesville, Missouri, was fought to the death.

Aside from mentioning a “family quarrel,” no details were given regarding the reason for the fight. However, surely to the readers’ delight, details of the fight itself were numerous. Both women acknowledged they were prepared to go all out, “until one of us is dead.”

The knives were fastened to their wrists and, as the paper reported, “like two frontier fighters they swayed this way and that, one now gaining the advantage, then another.”

When Mrs. Graham drew first blood with a stab into Mrs. Crabtree’s shoulder, “the sight of blood unnerved one of the seconds, who promptly fainted away.” But this didn’t distract the combatants. The struggle continued until Mrs. Crabtree finally swung her knife and struck her sister-in-law’s throat.

“With a sharp gurgle Mrs. Graham fell to the ground, the blood spurting from an ear to ear cut,” the article described. “No sooner had Mrs. Graham fallen than Mrs. Crabtree fainted and fell across the body of her dead sister-in-law.”

The reporter commented that the duel might lead to a broader family feud. And presumably, more bloody duels.

A year later, two “old men” in New York City settled their grievances in the basement of the grocery store where both were employed. The duelists were John Ferris, 56, and William Wood, 72. Ferris had worked at the grocery store for thirty years, compared to Wood’s eighteen-year run, and thus continually referred to the elder man as the “newcomer.”

One night Wood arrived late to work due to a January blizzard in the city. Ferris gave him grief for his tardiness and the two bickered for hours well past midnight. Finally, they decided to put an end to the arguing with a duel. Ferris proved to have the faster draw and sharper aim.

Though you don’t see these kinds of duel-related headlines anymore, the idea may, in some circumstances, have some merit. In Barbara Holland’s book on the history of dueling, Gentlemen’s Blood, she shares a story from 2002, when relations between America and Iraq were heading toward war.

She noted that the Iraqi vice president suggested dueling as a simpler way to settle the conflict: “A president against a president and vice-president against vice president and a duel takes place, if they are serious, and in this way we are saving the American and the Iraqi people.”

Clearly the challenge was not accepted. But it does make for an intriguing alternative to war.

![Artificial nose, 17th-18th century, made of plated metal. Such noses would have been made to replace an original, which may have been congenitally absent or deformed, lost through accident or during combat or due to a degenerative disease, such as syphilis. By Science Museum London / Science and Society Picture Library [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.weirdhistorian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Artificial_nose_17th-18th_century_By-Science-Museum-London-Science-and-Society-Picture-Library-CC-BY-SA-2.0-via-Wikimedia-Commons-235x190.jpg)