J.W. Ocker and I are both authors at Quirk Books. We share an editor and we share a love of the strange and usual. I’ve written about Martians, ghosts and UFOs and he’s about cursed objects, cryptids, and cults. On the side, I run this site, Weird Historian, while Ocker runs Odd Things I’ve Seen. We even both maintain day jobs in advertising. So I figured our weird worlds should come together for an interview, which is transcribed below.

If you follow Ocker on social media, you’ve surely seen photos of his frequent travels to odd places (to see odd things) with his kids—which is where our conversation begins.

WH: It’s great to chat with you—your books are wonderful, and it’s clear you have a blast writing them. I see you post a lot of photos of you with your kids during your travels for research and it looks like they’re loving it. Do they enjoy going on these journeys with you? And what do they think of your books?

JWO: They’re so into it. They love the books. So this is probably the best thing about writing for me. When my mom died in 2016, that was the first time I ever faced mortality, thinking what the hell am I doing with my life? And what I landed on is, at the end of the day, I’m creating stuff for my children. It’s kind of become their identity as well. My kids range in age from six to 14, and when they were very young it was hard. They didn’t like being in the car a lot. They got sick, whatever. As they’re growing older, they’re almost liking it more than I do. We’re going to the Pine Barrens this weekend just because the girls found out about The Jersey Devil, got obsessed, and now they want to go see the Pine Barrens. So, like, it’s not even my trip. One of my daughters has cryptid stuff all over her walls. I have three kids books out and they’re always reading those and bringing them to school. They want me to come do talks. So it’s become this amazing bonding situation that’s alien to me, because I didn’t have this with my parents at all. I still don’t know what my dad did most of the time for a living. Something vaguely electronics, or something that, but like, this is real bonding. We talk about the books, we talk about going places.

When we go see something, I need to take a picture of it with myself, because that’s my gig, right? Odd Things I’ve Seen and I’ve been taking selfies since before selfies were a thing I said to use, like tripods and digital cameras and stuff. And now those group shots are literally those girls pushing their way into the frame. It’s been amazing. My family fell into hard times a couple years ago: divorce, death, stuff like that. So bringing my girls along on these trips has become the most fulfilling part of writing these books. They can be a part of it, they can be the first to read the manuscript, all that kind of stuff. The most important part is that relationship.

WH: I love that. I’ve been writing about sideshow performers for a long time, so we know a lot of unusual people who are friends now. My kids grew up around a lot of performers in that community: sword swallowers, fire eaters, a knife thrower. They’ve even fed two-headed turtles. When my older daughter wrote her college essay—she didn’t let me read it until after she got accepted—she started off by talking about meeting all these people who did these amazing things, who did the impossible. And then she spun that into if they could do the impossible, why couldn’t she do the impossible? Her impossible wasn’t sideshow, it was challenges she’s had to deal with and overcome in life. I love that these experiences left a powerful impression.

JWO: Yeah, it’s great. I tell my kids, you want to find the people who are interesting and make those your friends. Those the people you want around you inspiring you. A lot of people are boring. Ignore those people. Find the people who are different, because they’re gonna be much more rewarding friendships in the end.

WH: Absolutely. Well, let’s go back a little bit. What first got you into oddities, and what point did you start writing about them?

JWO: That’s a pretty clear line for me, because I grew up hyper-religious and in a very small fish bowl and not very plugged into pop culture. And then I found myself in maybe 2004 or 2005, I was in this tiny, dumpy apartment in Brunswick, Maryland, right on the train line. I’d already graduated from college and already earned my master’s, and I was depressed. I was alone. I had no girlfriend, no friends. I was kind of like, not suicidal, but depressed, so that you’re thinking about what would it be like not to exist anymore. And I thought, ‘Oh, man, I’ve done nothing.’ I vaguely knew I wanted to be a writer, but I wasn’t writing. I needed to write something, but I literally had nothing to write about. I was a boring dude in a boring situation with no ideas, and at the time, there were a few shows out and a few books out that got me into oddities. I realized, if I were to write about something, if I want to be interesting enough to write about stuff, I need to find the interesting thing. So if I can find something weird and write about that, I can be boring. It’s okay if I’m boring, if I’m writing about an interesting thing. And so I just started jumping in my car and driving to nearby things. I would drive an hour away, and then I would drive two hours away, and then every weekend, I would go longer and farther, and then I started a website. That’s kind of what happened—a blogger.com, website, where I’d chronicle these weird places I would drive to. And then that’s what blew up for me and gave me the book opportunities. It was like boredom and depression and realizing that there’s nothing much to you, so go find cool stuff elsewhere, you know. It was literally just a survival mechanism.

WH: What was that first weird place you drove to?

JWO: The town I lived in, Brunswick, was the next town over from Burkittsville, Maryland, which is where Blair Witch takes place and was filmed. So I went over there and I took pictures of the cemetery—I was a big horror fan already at that point and I wanted to visit more horror filming sites. So that was the first one, then the five I launched my website, OTIS [Odd Things I’ve Seen] was the Mothman statue in West Virginia, because, again, I was in the Mid Atlantic at the time, then a statue called The Awakening, which was this giant clawing his way out of the ground in DC at the time, then it was the Orson Welles memorial in Grovers Mill, New Jersey, and then it was strangely enough, the Great Pyramid of Giza, because I was working for an ocean technology magazine and just happened to get a free ride to Egypt to report on something over there. So Mid Atlantic sites is where I started.

WH: That’s a great start! How did it all lead to your first book?

JWO: The first book was The New England Grimpendium. At the time, the OTIS website caught on and got a bunch of followers. It was actually my second website—I started my first one in 2000 with a friend of mine, and I just fell in love with nonfiction writing at that point, because that’s the voice of the internet. It’s nonfiction, you could write whatever’s in your head. This was a nascent Internet, it didn’t matter. I could write a thousand words about this obscure episode of a sitcom or the Book of Job in the Bible. Nobody’s stopping you. You just hit “publish.” So when I started the new site, OTIS, about seven years later, I had one guy contact me and say, “Hey, this could be a book project. I don’t want to be your agent, I just want to pitch this one project to one publisher.” It didn’t work out because it was scattered, there was no theme. It was just what I found odd or whatever and that I could personally get to. That’s kind of a constraint. So at that point, I was starting a new life and I’d always wanted to live in New England. I finally got a job opportunity there so I moved with my fiancée at the time. Almost the second I landed in New England I had this giant list of odd things I wanted to see. New England’s full of the stuff. And at that point I realized New England is an angle. Random oddities that I’ve seen is not an angle for a book, but New England oddities are a very specific angle. So I put together a pitch for New England literary sites and another pitch for New England death-related sites and I sent them off to one local publisher. I figured a local New England publisher will publish the New England book. It was called Countryman Press in Vermont. Turns out they were local, but they were owned by W.W. Norton in Manhattan. I had no idea. They didn’t like the literary sites idea, but they loved the death-related sites idea, and that was it. I spent the next six months driving 7,000 miles around New England seeing all these sites I wanted to see and then writing about them.

WH: The book truly becomes an adventure.

JWO: I consider my nonfiction almost biographical. I always tell people having a nonfiction book at the end of a project is just a cherry—the experience is way more worth it, seeing cool things, getting access to cool things, I have friends from some of these projects.

WH: I totally agree! Let’s fast forward to your latest book, Cult Following: The Extreme Sects That Capture Our Imaginations―and Take Over Our Lives, from Quirk. What was it like to dive into that world? Cults seem like a scarier place than the worlds of cryptids or cursed objects. How did you approach it?

JWO: It was purposefully chosen for that reason, because it was a little bit different. Now, in a way, it’s been a vein I’ve always been interested in. When I go see oddities, cult sites are part of it. I’ve been to cult communes before, I’ve been to the Jonestown mass grave in Oakland, and I’ve been to the Koreshan Commune in Estero, Florida. So I was always interested in cults as a pillar of oddity. But there were two reasons why I pitched this book. One was because I came out of a very, very, very, very conservative sect of religion. So those kinds of religions interest me as a result. But the other thing is, my style is very nonchalant and jokey, which fits well when you’re talking about Bigfoot or you’re talking about a cursed dresser drawer. That tone fits that. But when I talk about actual abuse and actual manipulations and actual tragedies, I wondered if I could still do that tight wire of treating the subject with respect, but also having fun with it, which is kind of like, I guess my angle for all stuff. Can I do that with really horrible situations? And that was the challenge I wanted to chase. Can I write about the Ant Hill Kids and people getting their arms staple-gunned to a table and all those unanesthetized surgeries, and those kinds of things? Could I do that but still keep my tone? Would I lose my voice if I wrote about that? And I think it worked. I write about true crime a lot, for instance. I’ve been to all the sites related to Boston Strangler and Jack the Ripper, and I’ve been able to deal with that without treating it lightly or disrespectfully, but still treating it with wonder. To me, horror is a type of wonder—the reason why awesome and awful are very much related. It’s shocking and awful that a human person can do these things, but it’s still a type of wonder. So that was the motivation on that book. But you’re right. It’s a very different book from Cryptids, Cursed Objects, Edgar Allan Poe, Salem, my usual shtick.

WH: I thought you did a great job keeping your voice. There’s so many sad, tragic things, but some of it is also just so ridiculous that it opens the door to inject a little playfulness in the tone.

JWO: It is ridiculous. Usually with my books I’m trying to find some insight that’s not normal. The one I found for Cults is that as weird as cults are, and as shocking—you always wonder how rational people join cults—it turns out it’s the most human thing to do on the planet. You know, a bunch of people joining together under a single cause, behind an impressive leader. Literally, that’s life, that’s family, that’s corporations, that’s politics, society, towns. So in some ways, joining a cult is the most human thing you can do, and once you kind of realize that, a) empathy helps, but b), it’s even more terrifying. If it’s the most natural thing we can do, and that natural thing almost always ends in abuse and tragedy, that fits my cynicism. It was a harder book to write than anything I’ve ever written before, because in some ways, it’s a mainstream topic, unlike my other books, which means there’s a ton of source material. I’ve gotta write 2,000 words about the Manson family? It’s impossible. Writing 200,000 words about the Manson family is very possible, but writing only 2,000 words about him is hard and again, all my sources are legitimate. Manson has Time magazines, newspapers, entire books written by the people who were involved, as opposed to, like, cryptids, where you’re digging through newspaper accounts and it’s a different style of research. It is the most mainstream thing I’ve done, I think, of all my works.

WH: I know what you mean by all that, too. There’s almost too much information. For my next Quirk book, You’re Not Supposed to Know About This, one of the sections is on the Manhattan Project, which was daunting because there’s just so much there. What do I cover? What don’t I cover? I mean, the biography on Oppenheimer that became the movie is like 800 pages or something. That’s just one source. So yeah, the challenge is how do I boil this down and make sure it’s interesting?

JWO: It’s why I’m finding this new book [Don’t Go There] to be so easy in comparison. Because even the Bermuda Triangle, which sounds like it’s a giant topic, is not that giant of a topic. The sources that cover it are mostly illegitimate, with just a few legitimate ones. But it’s so much easier than real life, true crime, or in your case, real historical events.

The story of the triangle is literally stuff disappears in the ocean. There’s tons of theories but there’s no stories on the theories. It’s not like there’s survivors that saw a shaft of light or other time zones. It’s literally things disappeared in an ocean. So the story for me is the story of how it became the most famous paranormal spot on the planet. How did that happen? That’s where I had to go, because if I just told the story of the triangle, it was just these planes disappeared and then this ship disappeared…

WH: That sounds like a fun story to be diving into though.

JWO: So much fun. Way more fun than cults.

WH: Diving back into cults briefly, was there one that stood out as more disturbing than the others?

JWO: You kind of get immune to it, like anytime there’s sex trafficking or sex abuse that was so common, you kind of got immune to that. But the one that really took me down was the Ant Hill Kids, which is a Canadian cult run by Roch Thériault. He was so brutal to his people. He would defile corpses and kill children and cut people open and pull people’s teeth out. But his cult started out as a clean-living cult. It was literally how to stop smoking and eat more vegan—something very, very benign. But as soon as he got power, and as soon as he isolated geographically up in the mountains of Canada, he just went off the deep end and the stuff he did was awful. As a male leader of a cult, he was inevitably gonna take every woman in the organization. One of his wives had her arm nailed to a table until it turned purple and they had to cut it off. And he burned her breasts and pulled her teeth out. And her quote, when he got finally busted and sent to jail was, “Yes, he did awful things, but normally he was a pretty nice guy.” That level of cognitive dissonance—that phrase came out of a cult actually—that cognitive dissonance was also very terrifying to me. This is such an extreme level, it was just sad and depressing. It was actually the first entry I wrote, because that was the test entry for me and my editor, Rebecca. I was like, all right, this is the worst thing I know of when I write about this thing. If it works, the cult book should work. If it doesn’t, it probably won’t. It’s probably not the project for me.

WH: That makes sense. Get the worst out of the way, which you did nicely. Let’s shift to the world of cryptids. Which creatures rise above the others in weirdness?

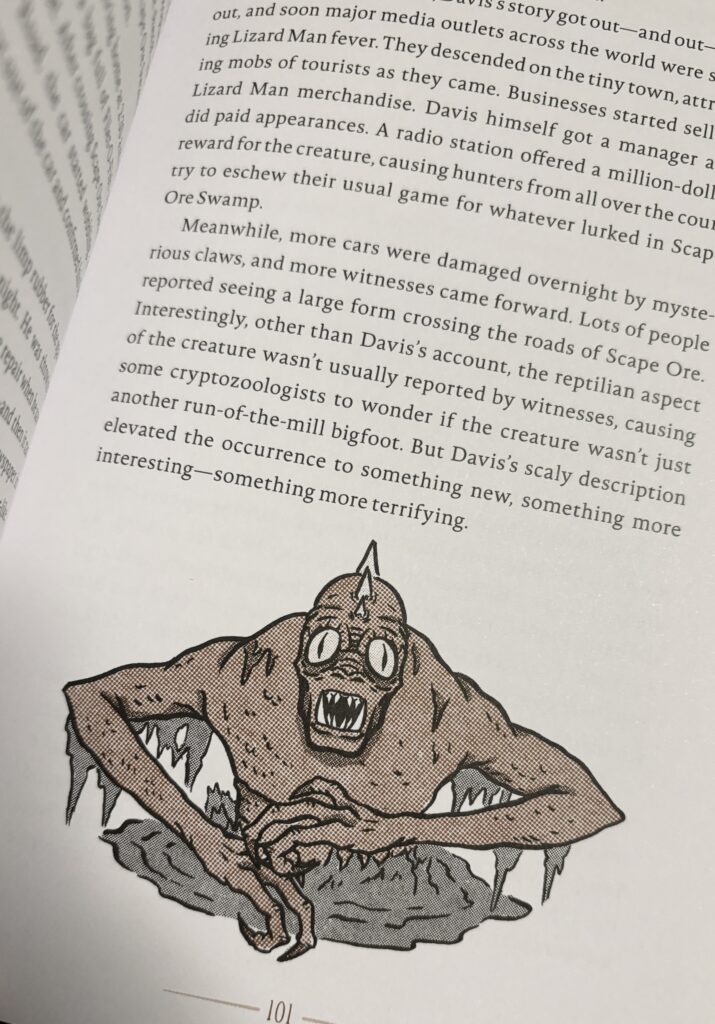

JWO: The ones that I always loved the most are the ones that had outlandish stories that were documented in papers. So it wasn’t just somebody saw something and then they describe it. It’s vague and dark and hairy and whatever. A good one I love a lot is the Lizard Man of Scape Ore Swamp. This is the story of a boy who worked at McDonald’s—he was a teenager driving home late at night. Somewhere he got out of the car and then suddenly he got chased by this red-eyed reptilian creature. And the real story behind that is he gets home, there’s scratches on the car and his parents ask him why he’s late and about the car. And he tells him the story—and there’s probably two truths of it. One was that he just kind of wrecked the car up a little bit on the drive home and had to invent an excuse why. And then that excuse just caught on into a major myth, which I love—that idea of a teenager’s white lie to his parents turns into the story that the entire community grabs and it’s in the museums now and all those kinds of things. He also might have just gotten chased away by a local farmer who was very protective of his land. But I love this idea of either there’s a reptilian humanoid in this in the swamps of South Carolina, or it was a kid just trying to get out of getting in trouble with his parents. I love those two extremes.

WH: And no one applied Occam’s razor to those possibilities.

JWO: What I see happen often, especially in the crypto world and in the paranormal too, is what I call reverse Occam’s razor, where, if the simple answer doesn’t pan out, then go weirder. So Bigfoot—we’re at Year 75 with no Bigfoot body. Now people are like, what if he’s a ghost? What if he’s an extra-dimensional visitor? What if he’s the pet of an alien? Because, again, the simplest answer, he doesn’t exist, is not fun for them. So they go weirder. They find theories that you can’t disprove at all. You can’t disprove that something is an extraterrestrial or an extra-dimensional visitor, right? You just can’t disprove that.

WH: Gotta keep that thing alive no matter what.

JWO: Yeah, no matter what. They literally can’t say, “Oh, I guess there’s no Bigfoot.” That’s just too destructive to their psyches, right? You see it in cults and religion too, they do the same thing where they have to get weirder and weirder because it’s so easy to disprove certain tenets, you know? So they have to get to a place where it’s impossible to disprove and impossible to prove, and then it’s just a matter of faith. And you can’t argue faith. It’s a very human thing to do.

WH: I always love the stories of Spiritualist mediums getting caught faking something, and then their supporters say they faked it that time because they can’t perform perfectly all the time, and they have to put on a show. But, they’d say, other times are real.

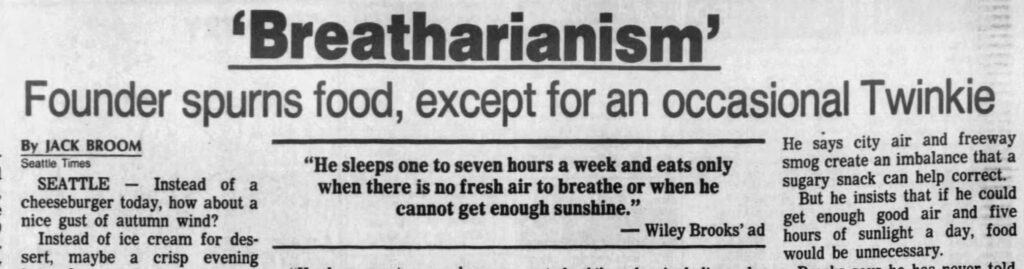

JWO: That’s exactly what happened with breatharianism. The head guy got caught coming out of a 7-Eleven with a Twinkie. And they were like, yes, he’s a fraud, but his ideas are not fraudulent. Again, we’ve got cognitive dissonance. I love that example. In the epilogue to Cult Following, I have seven things that all cults seem to have in common, and one of them is you need a revelation that you know hasn’t been around for thousands of years, things that I’ve never heard in my life—a real revelation. And breatharianism falls in that category for me. Somebody tells me, “You know what, eating is a fraud. You never have to eat.” To me, that shakes reality. Reality trembles a little bit. If true, that is the most amazing revelation I’ve ever heard.

WH: Plus, it’s a great money saver and you get a lot of time back.

JWO: Yes, we have a fraught relationship with food. We take that line out of our budget and we’re all rich. Or the anxiety of losing weight and gaining weight, that’s gone too! It serves a definite psychological need that we have. In fact, I met somebody—this was actually scary—my first talk about Cult Following was at this Barnes & Noble in Connecticut and they asked me questions at the end. I brought up breatharianism, because I will never not bring it up for the rest of my life, and this kid who was probably twenty-five and skinny, said, “Oh, I know about that group.” I said, “Yeah, it’s crazy, right?” He said, “Well, I’ve been trying to research it, because what if it’s true? I’m trying to save money.” He was dead serious. He was researching this on YouTube (of course) because he thought it would be a good way to save money. I guess he was probably having trouble making ends meet and it appealed to that one sense of saving money. So it doesn’t matter if it’s false or weird or sounds bizarre.

WH: You’d think eventually the starvation would be a real downside. One last question. When I’m doing interviews about my books, I’m always asked if I’ve seen a UFO or a ghost. Do you get that as well? Questions about seeing strange creatures or encountering haunted objects?

JWO: All the time. I do talks with ghost hunters and I have to give them a boring answer. I have to tell them, you know, no, I don’t believe in any of this stuff. But I tell them I’m a cynic, and I don’t believe in anything from true love to ghosts—like the entire gamut. But I also tell them that, there’s a few caveats. One is when I say I’ve never had an experience, I do believe we’re all one experience away from believing anything on the planet for sure, but I tell them I’m a guy who has spent nights in abandoned prisons and asylums and cemeteries and murder scenes—I’ve done that, I’ve done the work—and I still don’t have a single story about it, or cryptids. Once upon a time when I was a Christian, I believed in everything, witches and ghosts and demons, and gods and I actually believed tons of stuff. So I know about the elasticity of belief. And this is where I’ll end it, so I’m not being too judgmental, because I just have never had an experience that convinces me. And of all the people on the planet, I should have. I’m looking for it. I’m definitely the “I Want to Believe” poster in Mulder’s office, but everywhere I go, nothing convinces me.

Find out more about the odd things J.W. Ocker has seen—and written about—at Odd Things I’ve Seen and at Quirk Books. Purchase his books at either site, or wherever you buy books. Reading about cults is way better than joining one.