In previous centuries, the bodies of executed criminals were often allowed to be dissected and studied by anatomists. At other times, however, the bodies were left hanging in chains for long periods of time until the scalps wore away and the exposed skulls, like a stone, gathered moss.

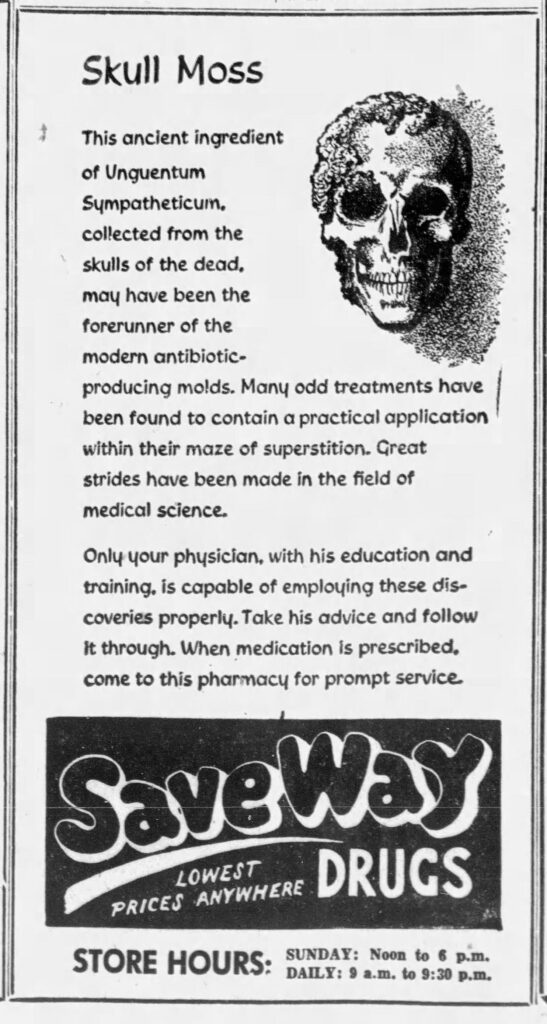

During this time of misguided remedies and quackery, this “skull moss” was believed to have curative powers. The hanging of criminals supposedly forced the spirit of their vim and vigor into the head. As a result, the potent moss—also called usnea—was used to help stop bleeding (like gauze or, you know, maybe a tissue) and, according to a 1927 article, “was sought after as a sure antidote for neurasthenia and kindred ailments.”

IFLScience.com adds that “consumers would take those skulls and scrape them for their lichens” which were then ground up and “used to promote wound healing, treat whooping cough, and manage epilepsy, among other things.”

This fuzzy medicine appeared in encyclopedias as early as the late 1700s as a serious treatment and remained an official drug in pharmacopeias and was sold in apothecaries.

In 1955, a newspaper ad for various pharmacies shared the strange skull moss history as an example of “odd treatments” and the “great strides” made in medicine—reminding readers to listen to their modern-day doctors and to bring prescriptions to their “pharmacy for prompt service.”

As bizarre as it sounds now, it surely seemed perfectly logical at the time. One can’t help but wonder what medical techniques and remedies of today will be mocked and laughed at in the next hundred years.