I originally wrote this article for Mental Floss.

As a young girl growing up in Milwaukee, Dr. Dori Ann Bischmann would explore her parents’ attic in search of lost memories. The mysterious trunk she discovered there one day in the early 1970s was a treasure chest that piqued her curiosity.

Inside, Dori found children’s china, an antique baby doll, a beaded hat and bag from the 1920s, and an old scrapbook. The book had a picture of two puppies on the cover.

The cover of Agnes’s scrapbook. Photo courtesy of Dori Ann Bischmann, PhD.

But the images inside weren’t cuddly as advertised.

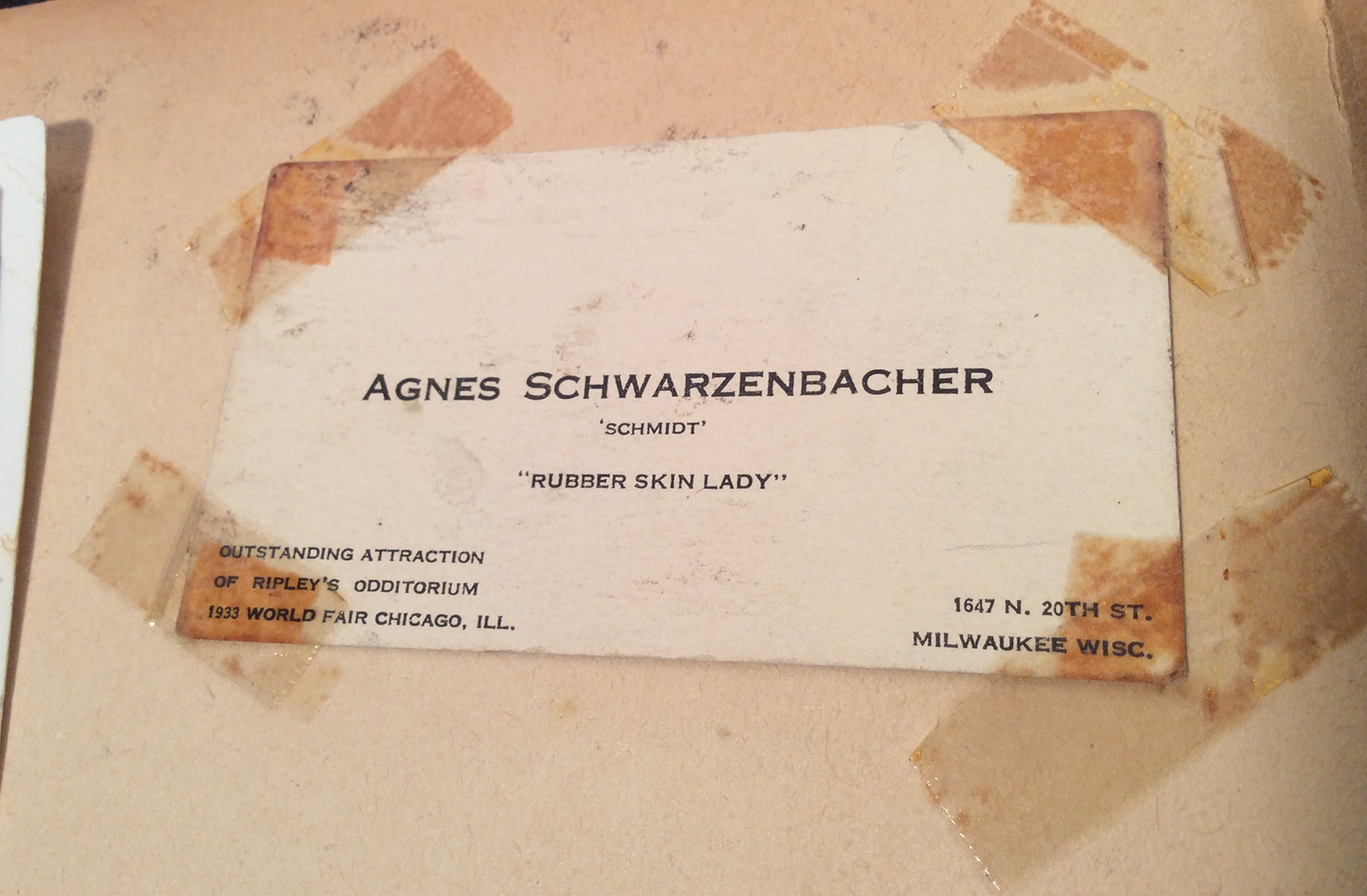

Dori had found the scrapbook of her great aunt, Agnes Schwarzenbacher, also known as Agnes Higginbotham and Agnes Schmidt—but more famously known as Agnes the Rubber Skin Lady. On the inside cover of the book a title marked in pen read, “Scrapbook of Show Life.”

The newspaper clippings, photos, and signed pitch cards (which were like postcards featuring individual performers) that fill nearly ninety pages gave Dori a glimpse into the life of one of the sideshow’s biggest stars of the 1930s. It also unlocked a family secret.

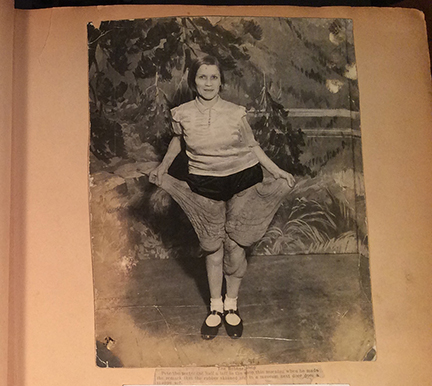

Dori had never met her aunt, who passed away in 1962. Nor had she ever heard about how Agnes drew crowds to watch her exhibit the excessive, elastic skin that covered her legs. Agnes could stretch the rubbery flesh anywhere from fifteen to thirty inches. From the waist up, she looked completely normal. There are no reports of a diagnosis, but she may have had a condition called Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome.

Aunt Agnes, who was born in 1902 in Germany and came to America three years later, had shared her unusual skin on stages across the continent. In Toronto, she even performed before royalty. In one of the scrapbook’s clippings, she spoke of the event as being one of the greatest thrills of her life on the road: “The audience was a very distinguished one and most famous of all was the Crown Prince of England, now the Duke of Windsor. I was most thrilled when he applauded vigorously.”

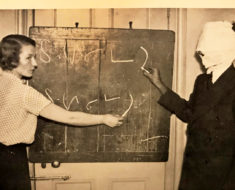

Agnes displays her rubber-like skin. Photo courtesy of Dori Ann Bischmann, PhD.

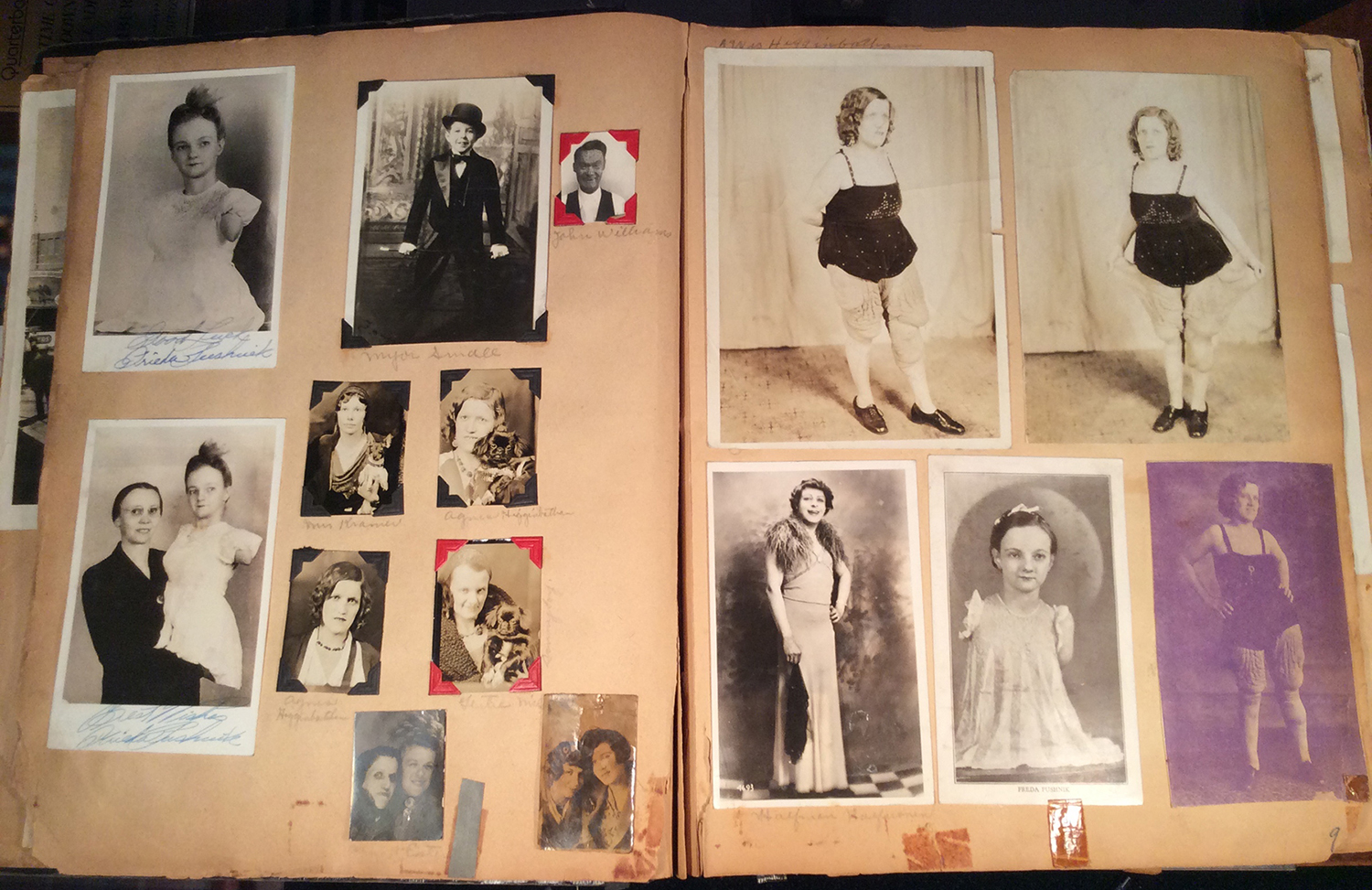

With each turn of the book’s pages, Dori encountered many of the extraordinary people Agnes performed with, particularly at the Ripley’s Odditorium at the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago. Robert Ripley’s Believe It Or Not! cartoon was at the height of its popularity, and the Odditorium was the first public exhibition of unique performers and curiosities he’d gathered during his travels around the world. More than two million people visited his collection and witnessed live acts like Agnes.

Dori was enthralled with her discovery. “I have always been fascinated with people who are unique,” she tells Mental Floss. Today, she works as a psychologist and often counsels people who have genetic disorders.

“I see a lot of amazing people overcoming many hurdles,” she says. “At the same time I see people who are depressed. I wonder how all of the circus freaks felt on the inside. Were they hurting and depressed and putting on a show outwardly? Or did they find contentment in giving something of themselves to help others?”

Agnes’s business card. Photo courtesy of Dori Ann Bischmann, PhD.

While it’s hard to know exactly how Agnes felt, there are glimpses in some of the scrapbook’s clippings.

“She used a circumstance she was born into to become an independent woman with a high-paying career (for the day),” Dori said. “She traveled and experienced many things other women might not have been able to experience.”

Indeed, Agnes’s skin ailment proved to be quite profitable. Several articles in the scrapbook claimed, “The salary paid her is the highest ever paid a freak.” No numbers are given, and like many sideshow claims, this was likely an exaggeration. However, if her earnings were anywhere near her fellow Ripley’s performer, Betty Lou Williams, she was doing quite well. Williams was not yet two years old when she began exhibiting the parasitic twin protruding from her torso. The young girl was reportedly earning nearly $250 a week with Ripley. If Agnes earned even half Williams’s pay, that would be more than $2,000 today—an impressive salary, particularly during the Great Depression era.

Agnes the Rubber Skin Lady and other performers, including: signed photos from Frieda Pushnik; a little person, Major Small; and John Williams, the Alligator-Skin Boy. Photo courtesy of Dori Ann Bischmann, PhD

The money, of course, made the idea of exhibiting her unusual skin very attractive. But Agnes didn’t just stand there to be gawked at. She used her platform to spread a message of positivity, reminding people that when life brings you twists and turns, you simply have to accept it, move on, and do your best.

The Rubber Skin Lady fully accepted her anomaly. “I would like very much to be normal in every respect,” she said in another of the scrapbook’s newspaper clippings. “Don’t misunderstand me. I said I would like to, but simply because my skin is rubber doesn’t mean that I have become morbid. Far from it. I am, perhaps, one of the most pleasant persons you ever met. And why shouldn’t I be? I don’t consider myself seriously handicapped. I realize that my skin when stretched isn’t exactly normal, but I don’t allow the presence of such skin on my body to make me self-conscious.”

The Schwarzenbachers, however, weren’t as self-confident as Agnes. Her family would’ve preferred that she covered her legs with long dresses and kept her anomaly to herself. They wanted nothing to do with her performances.

“The family was embarrassed that she was in the circus,” Dori told Mental Floss. “I was also told that Agnes went to doctors to see if the tissue could be cut off. Apparently they couldn’t in those days because it was too vascularized.” (In other words, her tissue was too filled with blood vessels.)

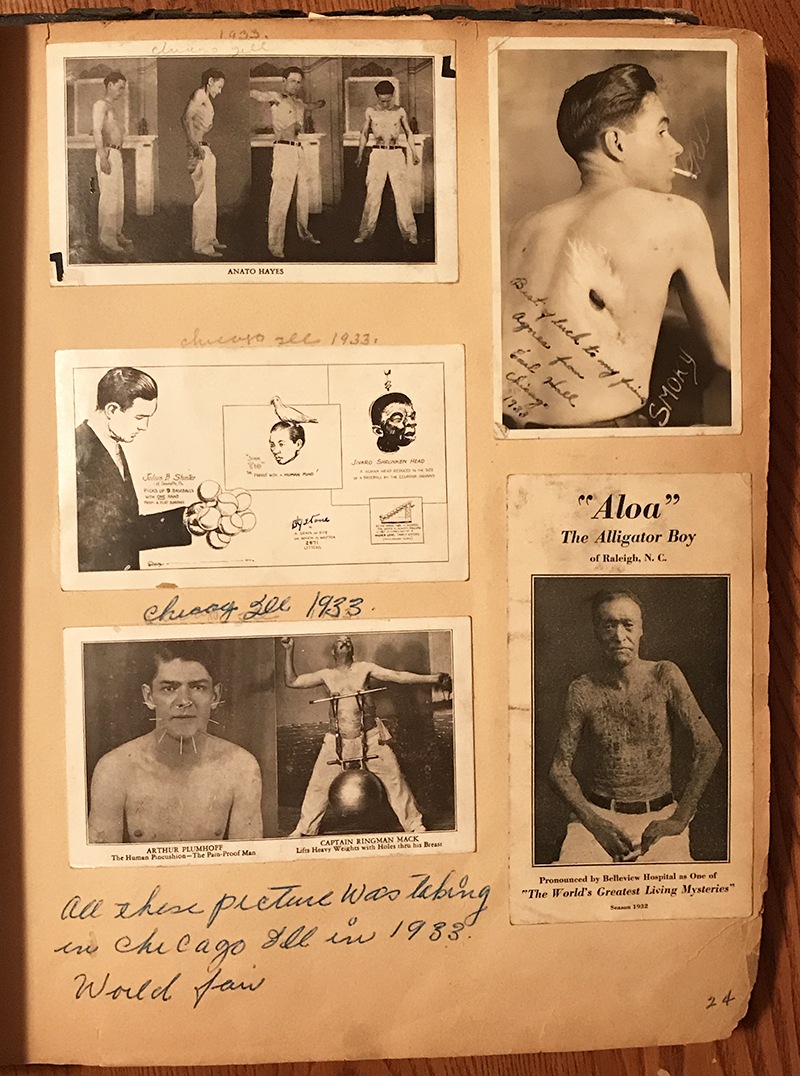

A collection of performers from the 1933 World’s Fair: Anato Hayes, The Anatomical Wonder; Earl “Smoky” Hall, who could inhale a cigarette and exhale the smoke through his skin; a Ripley’s cartoon; a souvenir postcard with The Human Pincushion, Arthur Plumhoff, and Captain Ringman Mack, who lifted weights with his pierced nipples; and William Parnell, known as “Aloa” the Alligator Boy, due to a condition called ichthyosis. Photo courtesy of Dori Ann Bischmann, PhD

The family’s shame lasted well after Agnes’s death. The scrapbook had originally been stored in Dori’s grandparents’ attic. When her grandmother passed away, no one in the family wanted the book except for Dori’s mother, who had married Agnes’s nephew.

“My mother was a person who was accepting of all people,” Dori said. “She wasn’t embarrassed about Agnes. She thought it was a shame that Agnes’s flesh and blood did not want her scrapbook. The scrapbook is the story of Agnes’s circus years, but also of her family.”

Of course, it wasn’t unusual for people born with anomalies to be treated in such ways. The sideshow, which had its heyday from the mid-1800s to the 1940s, offered them a chance to escape a life of seclusion, earn a living, see the world, and perhaps most importantly, to enjoy a sense of camaraderie.

In a 1959 article from the New York World-Telegram and Sun, longtime showman Dick Best expanded on this thought more colorfully: “For the past thirty years I have been able to give employment to scores of [freaks], give them financial independence, and companionship. You realize this when you see a mule-faced girl, a guy with three legs, and a girl weighing 500 pounds playing poker with a guy who shuffles and deals with his toes. In a crowd like that nobody sits around feeling sorry for himself or anybody else. You could be accepted there if you had nine arms and ten heads.”

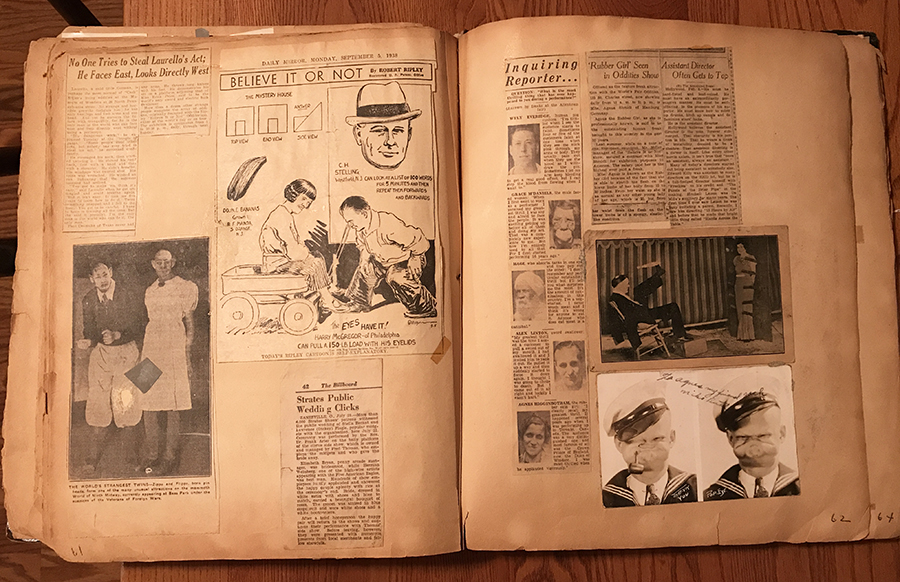

In addition to clippings of newspaper articles about Agnes the Rubber Skin Lady, this spread features: a Believe It Or Not cartoon starring Agnes’s friends, Lillie and Harry McGregor, who could pull each other in a wagon with their eyelids; an article about Martin Laurello, known as the Human Owl, for his ability to turn his head 180 degrees; a piece about performers with microcephaly billed as “The World’s Strangest Twins”; a clipping from The Billboard about the marriage of two “popular midgets” from the James E. Strates Shows carnival; a photo of armless knife thrower Paul Desmuke; and a signed photo of Popeye impersonator, Mike Butch. Photo courtesy of Dori Ann Bischmann, PhD

Lillie McGregor, a friend of Agnes, pulls an unidentified man in a wagon with hooks attached to her eyelids at the 1933 World’s Fair. Photo courtesy of Dori Ann Bischmann, PhD

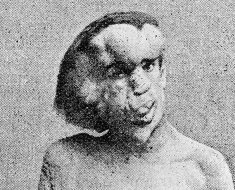

The “mule-faced girl” that Best referred to was Grace McDaniels, who Agnes worked with and featured in her album. McDaniels was afflicted with a condition that caused tumors to grow on her lips and mouth. In addition to being called “mule-faced,” she was also billed as the Ugliest Woman in the World. Agnes’s photos show her with her teenage son, Elmer, who traveled with her.

The “guy with three legs,” as Best called him, also appears in the scrapbook. His name was Francesco Lentini, billed as the Three-Legged Wonder. He also had four feet and two sets of genitalia.

Agnes’s friend Frieda Pushnik, the Armless, Legless Girl Wonder, is featured more prominently. Born in Pennsylvania in 1923, Pushnik had only small stumps at her shoulders and thighs with which she learned to do such things as sew, crochet, write, and type. At the age of ten she joined the Rubber Skin Lady at the Chicago Odditorium during the World’s Fair.

In addition to having collected several of Frieda’s pitch cards, Agnes also had personal photos. One of these captures another companion, a dwarf named Lillie McGregor, holding little Frieda. Without legs, Frieda is about half the size of Lillie.

Lillie appears in other photographs with her husband, Harry. They are each seen pulling a person in a wagon with their eyelids. Agnes even saved the Ripley’s cartoon that illustrated the stunt.

While Agnes’s adventures in show life surrounded her with many kinds of unique people, one photo is of a man who shared a similar ailment. Arthur Loos, the Rubber-Skinned Man, had skin that hung loose beneath his chin, much like a basset hound’s. He could stretch the flesh eight inches. If they bonded over their sagging skin, Agnes made no mention of it in the scrapbook.

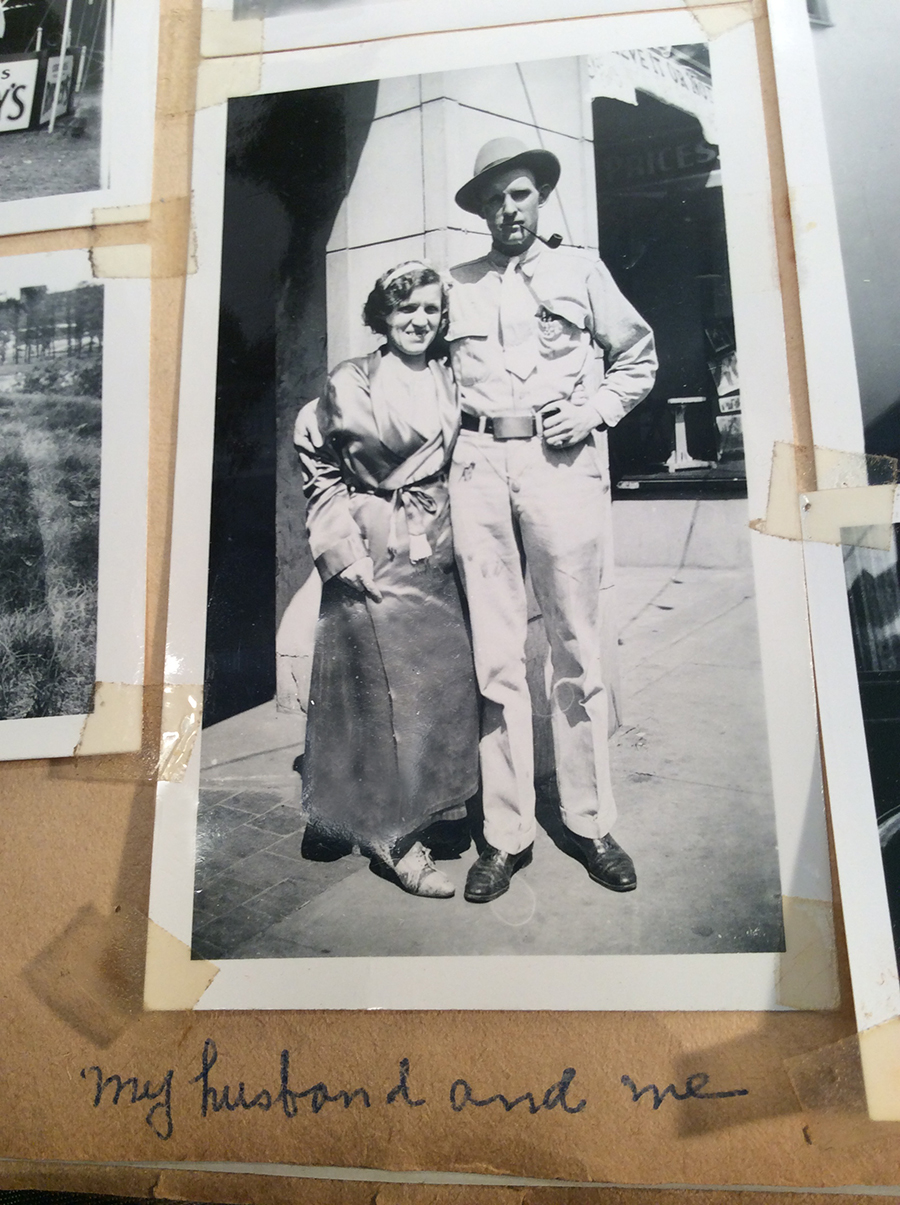

Agnes with her husband, Jack Higginbotham. Photo courtesy of Dori Ann Bischmann, PhD.

The man she did bond with was not a performer in the sideshow at all. He was a foreman who operated rides at a fair, named Jack Higginbotham. Their marriage is mentioned in one of the articles, which states they were wed in Rockford, Illinois. However, the Rubber Skin Lady’s love story was a mere subhead to another sideshow romance that earned the paper’s headline: “Bearded Lady and ‘Elephant Man’ on Midway are Newlyweds.”

At the top, a photo featuring Agnes Schwarzenbacher with her father and siblings: Mary, John, Rose, and Carl. Below is a portrait of Agnes dated 1926. Photo courtesy of Dori Ann Bischmann, PhD

Although her family may have stayed far away from the sideshow stage, Agnes kept them all close. Photos of her with her father, brothers, sisters and other family members populate numerous pages of the scrapbook.

Had Dori only seen these particular family photos, with her aunt’s dresses covering her legs, she would have never known Agnes was different in any way—or what an amazing story she had to tell.